Illustrations by Sachi Kitajima Mulkey.

Illustrations by Sachi Kitajima Mulkey.

This past September, in slack-calm waters, Captain Steven Melz and his deckhand performed an experiment. Fathom by fathom, five different styles of crab traps dropped beneath the surf, delivering lunch to Dungeness crabs waiting on the ocean floor. Despite a century of unchanged crab trapping techniques, Melz hopes to find alternative gear that can sustain the future of the beleaguered Bay Area Dungeness crab fishery, and solve its biggest — and perhaps surprising — problem: whales.

Whales are a big problem for crab fishers, or depending on who you’re asking, crab fishing is a big problem for whales, which can become entangled in the ropes attached to crab fishing traps.

After whale entanglements in the ropes attached to crab fishing gear spiked, a 2017 lawsuit resulted in new whale-safe restrictions on California crab fisheries. Although crab fishing season historically opens in November, for the last several years, lingering whale populations in the area have delayed the start of the season until after the valuable holiday market. Experts and fishers predict these truncated seasons will become the new normal.

“I would love it to be the way that it was,” said Melz, a commercial crab fisher who began crab fishing on his late father’s boat over 30 years ago. “But that’s not going to happen.”

In dedicated working groups, state regulators, game wardens, ecologists, and fishers collaborate to innovate viable whale-safe gear. As numerous other strategies to make conventional gear safer have been implemented, finding a mutually-agreeable alternative crab fishing gear has become a central sticking point. With their livelihoods at stake, some fishers have taken innovation into their own hands.

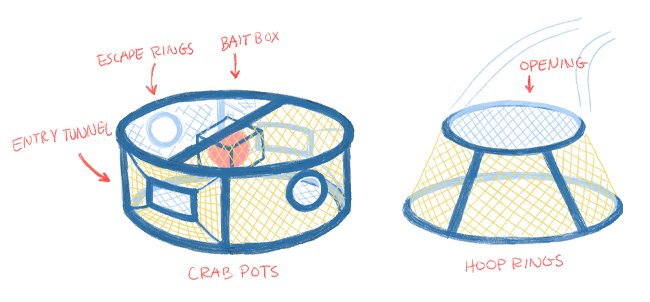

“Crab pots,” the conventional gear for trapping crabs, hold bait inside four-sided closed woven cages. Crabs enter through tunnels in the netting, while escape rings allow for smaller crabs that don’t meet regulated size requirements to exit. Crab pots rest on the ocean floor and are attached to floating buoys that mark their location through a vertical line of rope, which whales can become entangled in.

Depending on their permit, fishers set out hundreds of pots a day, which often remain in the water for multiple days. But the longer that ropes remain in the water, the higher the chance of entanglement with a whale, which can result in injuries or death. The whales, snagging their fins and bus-sized bodies on the ropes, can drag gear for thousands of miles, embedding the ropes into their flesh and creating challenges around identifying the origin of the fishing gear.

Entanglements happen as whales migrate down to their winter breeding grounds in Mexico, and pass through the Bay Area’s Dungeness crab fishing zones. As climate change warms ocean waters, this migratory timing has shifted, overlapping with crab fishing season along the west coast.

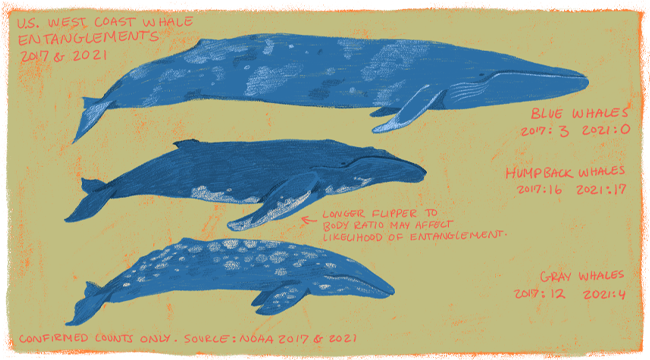

Prior to 2013, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) reports an average of 10 whales per year confirmed to be entangled in fishing gear along the U.S. West Coast.

But in 2015, a warm water event known to ecologists as “the blob” resulted in a drastic increase of whales in the Bay Area during crab season. The number of entanglements almost doubled from the previous year. By the end of the season, 50 whales, primarily Humpbacks, had been recorded to be entangled along the west coast.

In 2017, the Center for Biological Diversity, an environmental activism nonprofit organization, sued the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), stating that these entanglements were violations of the Endangered Species Act, which protects Humpback and Blue whales.

“It’s really clear that lawsuits by private citizens and environmental groups are absolutely crucial to making sure that laws work,” said Patrick Sullivan, Media Director for the Center for Biological Diversity. “We just see it as part of the democratic process.”

In response to the lawsuit, fishers in both the recreational and commercial sector say they feel disproportionately targeted as the “low-hanging fruit” compared to other industries, such as cargo ships that collide with whales. Data shows that these are a leading cause of whale deaths and have a high fatality rate. But on the West Coast, these events are difficult to document as many whales sink before they are found; Experts say as few as one in 10 whale strikes are recorded.

After negotiations and an intervention by The Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations, which represented crab fisherfolk, the lawsuit reached a settlement, and CDFW developed programs to regulate crab fisheries, based on a yearly risk-to-whales assessment.

“They want a program where they can shorten seasons, pull gear in, reduce the number of [ropes in the water],” said Ryan Bartling, a Senior Environmental Scientist on the Whale Safe Fisheries Project. As part of the settlement, the Dungeness Crab Fishing Gear Working Group was formed to brainstorm whale-safe gear alternatives with input from all stakeholders.

“[The crab fishery] is a shell of its former self because of the regulations,” said Captain Larry Collins, who is President of the San Francisco Fisherman’s Association and member of the Dungeness Crab Fishing Gear Working Group. “We call it death by 1,000 cuts.”

As part of risk assessments formulated by the group, NOAA scientists now conduct an aerial survey of whale populations before the start of each crab fishing season. If too many whales are detected, the season remains closed until the next survey. If entanglements are detected, the season closes early.

Fishers face many challenges from both the delayed season starts and early closures. For several years, crab fishers have missed the lucrative Thanksgiving market for crab, which is a traditional holiday food in the Bay Area. Fishers also say that starting as late as January means more dangerous weather, competition from northern fleets and large wholesale companies, and that the unpredictable timing adds high costs to retain crews.

“We call it death by 1,000 cuts.”

“I like whales,” said Collins. “But now whales are costing me $50,000 to $70,000 a year.”

Whale populations are increasing and have continued to remain in high numbers through the start of Dungeness crab fishing season in November. “The season is not going to look like it once was, just based on the data we’re seeing,” said Bartling. “There’s still going to be a crab fishery, it’s just going to look a little bit different.”

As part of the working groups, stakeholders modify existing gear to be more whale-safe, and review proposals for alternative gear that could allow fishing during season closures with lowered whale entanglement risk.

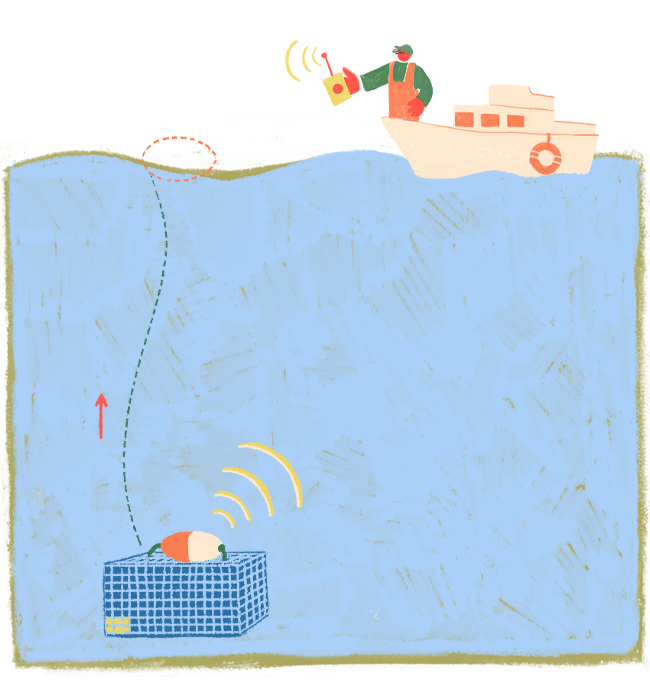

One of these proposals is a new gear technology in development, known as pop-up gear or by the misnomer, “ropeless” gear. Pop-up gear reduces the amount of time ropes spend in the water by storing the buoy and rope on the ocean floor with the crab pot, rather than connecting the crab pot to a buoy on the surface through a suspended vertical rope. When triggered by a remote control or a preset timer, the popup gear releases the buoy and rope, which float to the surface to be retrieved by a fisher.

Fishers remain unconvinced that pop-up gear is viable, citing the difficulties in operating as a fleet around unseen gear, unfeasible costs, and high rates of failure during tests.

Without a surface buoy design marking its location, fishers are concerned with overlapping as each boat lays hundreds of crab traps in the same zone, which can lead to tangling, lower catches, and gear failure.

“They think we lose gear now?” said Collins, who participates in a lost-gear retrieval program. “You gotta be able to see the buoys [on the surface of the water] so you don’t tangle with everybody and their brother.”

At over $1,000 a pot, pop-up gear could be over three times more expensive than conventional crab fishing gear. If the buoy fails to pop-up, the gear becomes irretrievable; lost pop-up gear may pose a larger risk to whales and boat engines, as fishers unwittingly lay gear on top of the unseen ropes below, and ropes from multiple sets of gear tangle with each other.

“It’s a huge capital investment,” said Captain Shane Wehr, a commercial Dungeness crab fisher with family roots in the San Francisco fishing community. “It would probably weed out half of the fishermen, and guys would sell out of the industry completely.”

Regulators and scientists see potential in pop-up gear. “I love the idea of ropeless gear,” said Dr. Elliott L. Hazen, a research ecologist at NOAA in Monterey, California, who sees pop-up gear as a promising technology that requires further testing. “How do you help fishermen avoid each others’ gear? If you can solve that problem, along with the sheer cost of ropeless gear, I think it’s an amazing solution. I really do.”

Although a $500,000 grant currently exists for pop-up gear testing, Bartling says few fishers have signed up to participate in gear trials. Fishers say they are wary of regulations that would force them to reinvest in the expensive pop-up gear if the trials are successful.

“It’s a fear from decades and decades of having their way of life stripped away,” said Captain Brand Little, a commercial fisherman. “If something gets taken away, its never coming back”

Captain Brand “Hoop Net” Little, received his nickname for his advocacy of another, less experimental type of alternative crab fishing gear as a solution to whale entanglements.

Traditionally used in spiny lobster fishing, hoop nets are shaped like volcanoes, with a circular opening at the top of a wider, circular base. Unlike crab pots, hoop nets have no other openings. Because of their open top which allows for crabs to escape once they have finished eating the bait, hoop nets cannot be left out for longer than two hours.

Due to this incentive to check hoop nets every two hours, the window for entanglement is much smaller. As two hours is too brief to leave the hoops unattended, any entangled whale would be quickly found, allowing time for the whale to be reported and potentially helped.

Hoop nets were first seized upon by the recreational crab fishery, which is also impacted by whale risk-assessment closures, but has separate regulations. Shortly after the delayed season started in November 2021, Captain James Smith, a former commercial crab fisher turned recreational charter boat captain, noticed that the text of the recreational regulations allowed for hoop net use during the closure.

“Everybody was trying to get their hands on hoops as fast as they could,” said Smith. Despite initial doubts from his peers on the efficacy of hoop nets, Smith was able to tweak his hoop net process to consistently make his catch limit of 10 crabs per net, per day. Once the word got out, charter boat businesses were able to salvage their crab fishing season by using hoop nets.

On the commercial side, Little, a participant in the Dungeness Crab Fishing Gear Working Group, then noticed that recreational fishers began fishing for crab with hoop nets, despite the whale-risk-related closures. “And we’re all just sitting here waiting,” said Little. “Why can’t I try these?”

But while they recognize the success of hoop nets for the recreational fisheries, some commercial fishers say hoop nets are a non-option for commercial fleets. “The guys that run my boats say, ‘F*ck hoops. F*ck ‘em from here and back,” said Wehr.

Compared to crab pots, hoop nets catch less crab and require more work. Due to the two hour window for operating each hoop net, fishers are concerned of the potential of retrieving gear during storms, which can form quickly on the water. Although the costs and set-up of hoop nets and crab pots are similar, many fishers feel reinvesting in new gear is too costly in both price and labor.

“All I can do is go out, use my boat, and try to come up with my ideas,” said Melz, who participated in pop-up gear trials, and decided to test hoop nets against crab pots for himself. He tested five variations of gear; three versions of a hoop net, and two versions of a crab pot.

The winner? A crab pot without a top, like a hoop net, but with the other design features of crab pots that add efficiency.

“I lovingly call them scoops,” said Melz, nicknaming the modified crab pot. With an open top, his scoops require the same short use-times that make hoop nets safer for whales. But unlike hoop nets, scoops are modified crab pots and would require fishers to simply modify their existing inventory.

The process for securing hoop net or scoop use commercially would require Little and Melz to go through the lengthy process of applying for an Experimental Fishing Permit, which would give a limited number of fishers an opportunity to fish with experimental gear.

Little said industry competition, alongside the fear of traditional crab pots being banned if hoop nets are successful enough, could put a “huge target” on his back.

“There’s $10 bills on the bottom of the ocean. There’s millions of them and it’s a race to pick them up the fastest,” said Little. “And now you’re sending 50 guys out there to get a head start? It’s not going to be popular.”

Some fishers say it’s time to revisit a reduced-gear solution they initially rejected and test the efficacy of the other numerous whale-safe improvements they’ve made to their conventional gear by setting only a portion of their gear out in the water. But due to the initial pushback, regulators are no longer considering this option.

Crab fishing season was slated to open this past weekend. But with over 100 whales detected off the coast, commercial fishermen have been benched for a fourth year in a row; Only recreational fishermen using hoop nets were permitted to begin their season.

“We’re stewards of the resource,” said Captain Richard Powers, president of the Golden Gate Fishermen’s Association, which represents Northern California charter boat fleets. “We’re doing everything in our power to be sustainable. We want this to remain exactly what it’s been: part of our heritage.”

Even though a solution won’t come in time for this year’s season, the commercial fleet, charter boat captains, regulators, and scientists say they are committed to collaboration and share the same goals.

“We’re working to solve this, not just because it’s the right thing to do, but because we want a viable fishery,” said Commissioner Eric Sklar of the California Department of Fish and Game Commission. He said that the stakes are clear: If whale entanglements continue to remain unsolved, it may mean the end of the Dungeness crab fisheries.

“There is not one fisherman who wants [entanglements] to happen,” said Captain Dick Ogg, a commercial fisher who assisted during NOAA sponsored Disentanglement First Responder courses, and participated during the aerial surveys of whale populations during entanglement risk assessments. “This is where we make our living. Why would we do something detrimental to the environment?”

After the working groups and regulations fulfill the conditions of the settlement, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife says the fishery could file for an Incidental Take Permit, which grants an industry with a permitted amount of yearly “take”. Take is defined as an unintentional, but expected, disruption or harm to a species of animal protected by the Endangered Species Act.

While incidental take permits have been called a “necessary evil,” many are in agreement that this would represent a last-ditch solution.

“Fishermen are the ones who are gonna want to protect [whales],” said Melz, who took the Level 1 Disentanglement Responder training. “Because if they fail, we’ll fail.”