Floods, hurricanes, and heatwaves: Climate change will intensify extreme weather in Illinois, report finds

By Eva Herscowitz

Although farmer Steve Stierwalt grows crops in the tiny town of Sadorus, Illinois — with a population of barely 350 — the agricultural practices he employs have environmental implications that stretch from Midwestern cornfields to Central American seas.

Fertilizer-polluted waterways in Champaign County, where Stierwalt farms, converge into the Mississippi River, emptying toxins into the Gulf of Mexico — where a 2,000-square-mile, pollutant-induced hypoxic zone makes aquatic life nearly impossible.

One cause of deoxygenated water in the Gulf? Water that falls from the sky.

“It’s pretty amazing the amount of energy each single raindrop has,” Stierwalt said. “When it hits bare soil, it’s like a miniature explosion. It displaces soil particles. Anytime that soil gets into surface water, it’s carrying nutrients with it. The nutrients, as we know, contribute to the hypoxic zone.”

To reduce soil erosion that Illinois rivers carry to the Gulf, Stierwalt has decreased fertilizer use and adopted conservation practices, like nutrient management tools that measure cost-effective and environmentally conscious amounts of nitrogen to apply to corn.

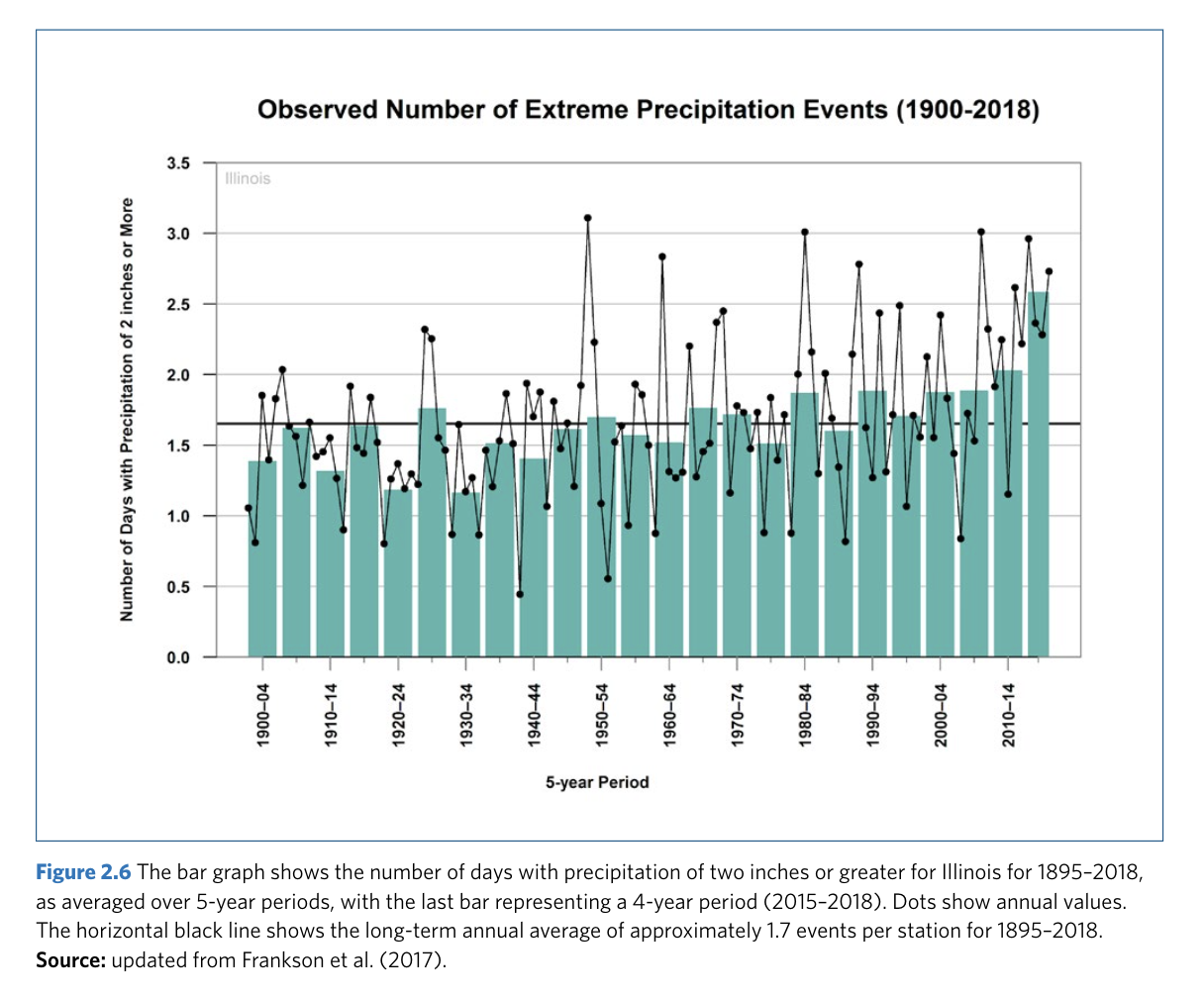

Sustainable agriculture practices — like rotating crops, planting cover crops, and eliminating tillage — allow Stierwalt to adapt to heavy rainfall, a form of extreme weather intensifying in Illinois. Indeed, science confirms Stierwalt’s observations: A major assessment released by The Nature Conservancy in April outlines how climate change will escalate periods of extreme heat, increased precipitation, and more intense storms in Illinois.

On farms, for instance, heavy rain and conventional tillage — ploughing, harrowing, and removing plant residue to prepare seedbeds — can trigger a chain reaction of climatic damage, contributing to soil erosion, and phosphate- and nitrate-infested run-off, resulting in pollution of the Gulf. These processes are already transforming Illinois, and no domain — from urban infrastructure to human health to plant biodiversity — will remain unaffected.

The report drew on the expertise of 45 researchers, scientists, climatologists, and policy-makers in Illinois, all of whom contributed to its stark findings.

“Climate change can seem like an overall threat that we don’t have any ability to change,” said Michelle Carr, Illinois state director at The Nature Conservancy. “When we look at state-specific data, and how it affects different industries that are prominent in our state, it allows those players to do more, because they’re seeing the specificity to their own geography.”

45 Authors, One Report

Co-led by climatologist Donald Wuebbles, former Illinois state climatologist James Angel, climate change project manager at The Nature Conservancy Karen Petersen and director of conservation science at The Nature Conservancy Maria Lemke, the 197-page report contains contributions from 45 specialists and covers the impacts of climate change on Illinois hydrology, agriculture, public health, and ecosystems. The statistics alone illustrate the projected scope of environmental transformation.

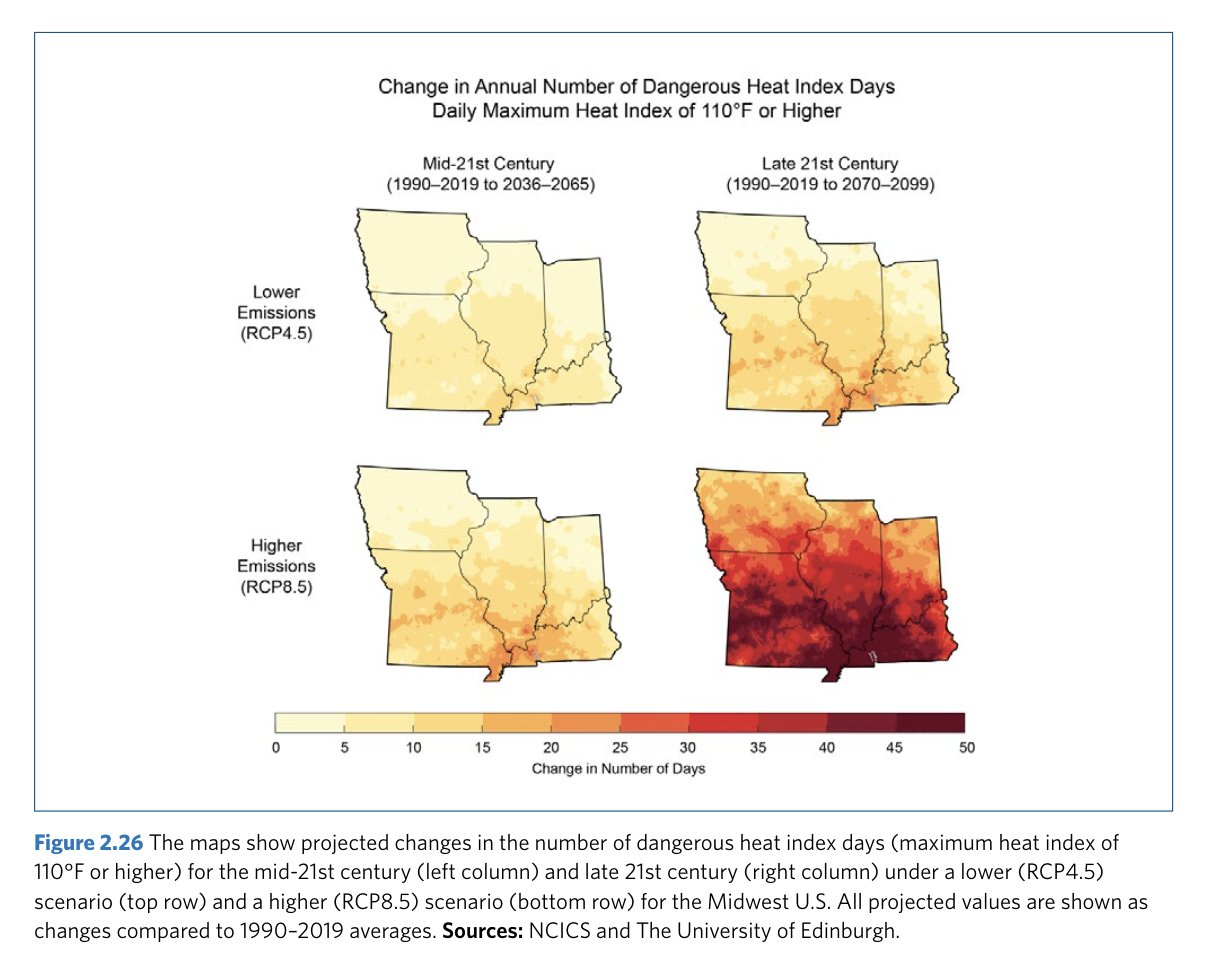

Accompanied by longer growing seasons and less severe extreme cold, temperatures will likely warm by 4 to 9 degrees F under a lower scenario and 8 to 14 degrees F under a higher scenario by the end of the 21st century. Longer growing seasons may sound like a bonus — but extremely long seasons can devastate, limiting crop diversity, encouraging invasive plant growth and straining water supplies.

The report also projects more rainy days and fewer snowy days by the century’s end, trends on the heels of a 5% to 20% increase in mean precipitation over the past 120 years. According to projections, severe weather will contribute to short-term droughts, as well as intense rain and flooding. Far from functioning as a minor inconvenience, flooding can delay planting, wash away fields of seedlings and destroy exposed crops.

Illinois residents can expect extreme heat by the century’s close, too. In Southern Illinois, for instance, scientists project the annual hottest 5-day maximum temperature to increase from 96 degrees to 100-107 degrees F under a lower scenario and 102 to 114 degrees F under a higher scenario.

“You see reports about fires in California or sea level rise in Florida, and you think it’s more of a coastal problem,” Petersen said. “We hope this report will help make some of those future impacts tangible, and for people to realize that climate change will have serious impacts in Illinois, and we can still do something about it.”

Wuebbles said land use and greenhouse gas emissions have remained the most significant contributors to climate change since the mid-1900s. Heavy emissions, he added, are unsustainable: the report projects that continued fossil fuel use will produce the most dramatic transformations, while a switch to renewable energy will net less extreme changes. A third scenario — which Wuebbles called “negative emissions” — will require scientists to harness technology to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

Regardless of the scenario, human activity will drive transformations in northern, central, and southern Illinois, said Wuebbles, a University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign professor who has contributed to several United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports.

“Illinois’ climate is expected to continue to change over the century, with significant impacts on urban and rural communities and sectors,” he said.

From Farming to Flooding

Consistent with the report’s predictions, Stierwalt has observed — and adapted to — extreme weather events. To protect soil, waterways, and farmland, Stierwalt practices no-till, strip-till, and cover crop farming — practices that sequester carbon in his soil while reducing nutrient pollution and soil erosion.

Currently the president of the Association of Illinois Soil and Water Conservation Districts, Stierwalt also serves on the steering committee for S.T.A.R., a nationwide program dedicated to “Saving Tomorrow’s Agriculture Resources” by helping farmers adopt conservation-based practices.

“Healthy soils are more armored against these extreme weather events,” Stierwalt said. “(Without adapting), the danger is losing this asset that we can’t afford to lose. We lose that soil for future generations.”

In conventional tillage, farmers use an implement to turn over soil, passing over the field multiple times and leaving barren soil behind. In no-till farming, farmers use planters or drills to cut a V-slot in the remains of previous crops, planting seeds within. Benefits of no-till include increased infiltration and soil fertility, and decreased labor costs and soil erosion.

Adopting sustainable agricultural practices, like no-till and drought-resistant crops, will determine the extent to which “future generations” of farmers face smaller crop yields, increased livestock illnesses, and increased crop diseases. Bill Miller, a Northwestern University engineering professor who contributed to the report, said “natural climate solutions” present promising ways to mitigate extreme weather. Cover crops, for instance, prevent soil erosion while strengthening soil’s biological properties. “It can help build up the richness of the soil,” Miller said.

Farming, though, is far from the only affected sector. Changing precipitation patterns are causing flooding events in the majority of Illinois’ gaged rivers and streams, exacerbating stress on urban drainage systems and increasing the incidence of combined sewer outflows. Northwestern engineering professor Aaron Packman, who also serves as director of Northwestern’s Center for Water Research, worked on the report’s hydrology team.

Packman said Chicago’s low-lying inland areas, particularly neighborhoods on the south and southwest side, are especially flood-prone. There, stormwater damage and inadequate infrastructure deplete property values, and chronic flooding carries waterborne illnesses. Across the city, extreme weather exacerbates geographical inequalities.

“The Loop has more than a hundred years of engineering to keep everything from flooding,” Packman said. “The lower-lying areas were settled later because they’re naturally more flood-prone, and they’re not as well protected by that centralized infrastructure.”

The Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago treats wastewater and provides stormwater management for 5.25 million people in Cook County, as well as a commercial and industrial equivalent of 4.5 million people. To mitigate the impacts of urban flooding and stormwater damage, MWRD has crafted stormwater management regulations for new developments, partnered with communities to better manage water and supported local green infrastructure projects.

Still, “policies, planning, tunnels and reservoirs cannot eliminate flooding alone,” MWRD public affairs staffer Patrick Thomas said. The report presents similar conclusions: Packman said a combination of sustainable water management in agricultural sectors, flood-control measures in municipalities, state-wide policies and consistent data collection might mitigate the harm climate change poses to Illinois’ water resources.

No Turning Back

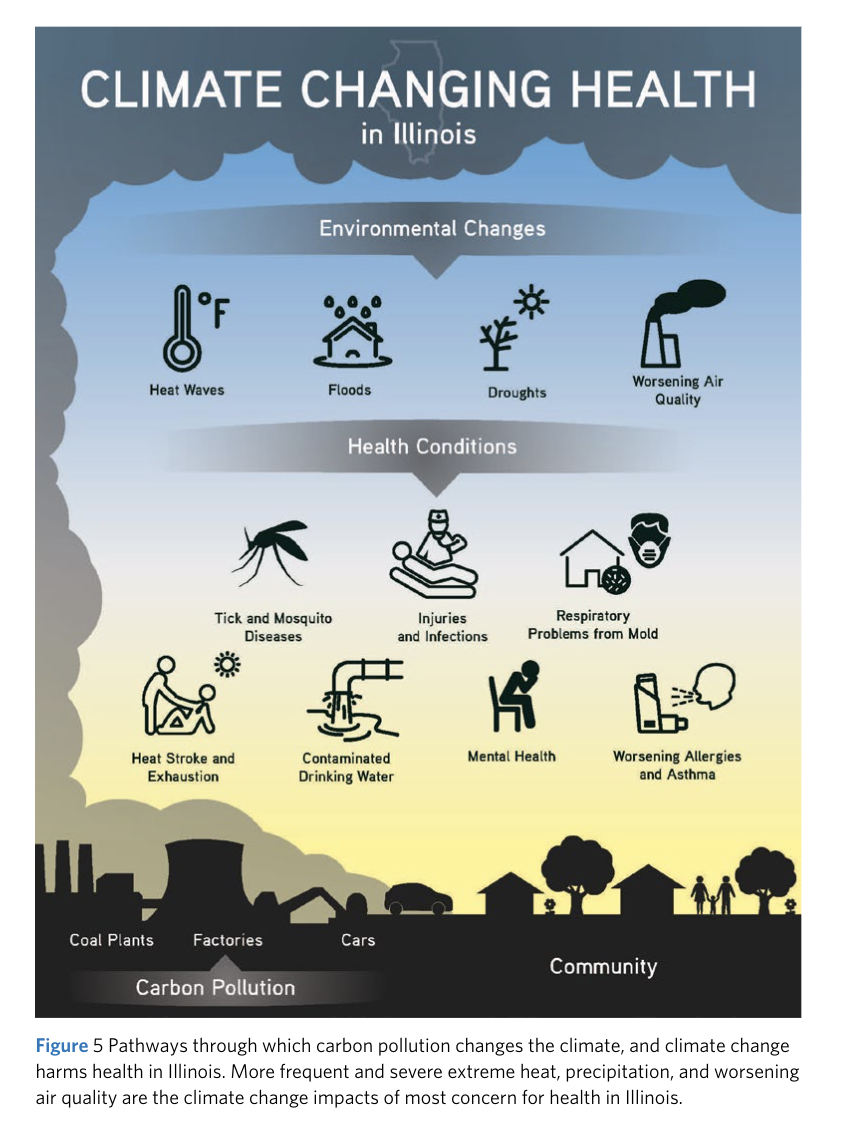

Prominent report contributors, including Wuebbles, participated in a May 17 panel to discuss the report’s results. During the panel, Elena Grossman, the program manager of Illinois’ Building Resilience Against Climate Effects program, reminded audiences that projected extreme weather will significantly harm our physical and mental health.

Contaminated drinking water, tick- and mosquito-borne diseases and respiratory illnesses will all increase amid intensifying weather — so, too, will psychological and financial challenges.

In the case of flooding, “there’s both the trauma of watching your home being flooded, of losing personal items, and then the financial stress of having to rebuild it or fix it,” Grossman said.

At its core, she added, the report is “about humans.”

In the month since the report’s release, Miller said authors have begun to discuss writing analyses that specifically address mitigation measures. As climate change continues to create extreme weather conditions in Illinois, reimagining the state’s infrastructure, policies and economic practices becomes increasingly urgent, Packman added.

“Climate change is a long-term process,” Packman said. “But in the last four years, we’ve seen unprecedented things, things that historically never happened. So it’s not something far off in the future. It’s something happening now.”

***

Q&A: Farmer Joe Rothermel talks soil health, sustainability

Joe Rothermel is a farmer who grew up in Broadlands, Illinois. He farms corn and soybeans on 1,000-acres in Champaign County. In 1992, his father, also a farmer, switched from conventional tillage to conservation-driven no-till farming.

Conventional tillage requires farmers use an implement to turn over soil, leaving barren soil behind. In no-till farming, farmers use planters or drills to cut a V-slot in the remains of previous crops, planting seeds within. Rothermel adopted no-till in 1995, and began supplementing this practice with cover crops in 2010.

Q: What are some of the advantages of farming with no-till and cover crops like alfalfa, rye, and clovers?

A: One of the reasons we plant cover crops is to help increase our soil health. One of the things you’ll notice is soil structure is improved. The ground is firmer. You can drive on it sooner. We have a lot of heavy equipment nowadays, and in a conventional program it’s easy to compact the soil. Conservation practices lend themselves to improving soil structure and holding up equipment so we don’t have as much compaction.

One of the main reasons to plant cover crops or to no-till is to reduce soil erosion. Through tillage, we’ve already lost half the organic matter that was originally in the prairie. Other potential benefits are nutrient recycling. The more biological activity we have, the more nutrient recycling. The idea is to use less synthetic fertilizer, less inputs. If we can maintain the same output with reduced inputs, that’s more efficient for the farmer.

And then the big thing is carbon sequestration. By not tilling the soil and using cover crops, through photosynthesis that will put carbon into the soil. Hopefully someday, that’ll be a source of revenue for farmers to help offset some of the costs of these conservation practices.

Q: How have extreme weather events impacted soil erosion and health?

A: It seems to rain a lot. We used to get a half inch [in a single rainfall]. Now, if we’re unlucky, we can get a two- or three-inch rain in a couple hours. I think we’ve cut down on some erosion; we still get some gullies. But compared to some of the other fields in the area, it’s significantly less. Some of the other conventionally tilled fields will have a cascade of soil coming off the field into the ditch. We don’t have that anymore.

It’s not perfect — but it does reduce erosion, especially if you have covers growing. We want the water to go down into the ground instead of running off, because when it runs off it takes topsoil with it. And then it takes nutrients with it. And then we have the hypoxia issue in the Gulf of Mexico. And so that’s another issue. Another reason to reduce tillage and grow covers.

Q: What percentage of Illinois farmers are practicing conservation agriculture?

A: In Illinois, less than 6% of farmers are growing cover crops, so there’s a long way to go.

Farmers are very independent. Older populations don’t like change. There’s peer pressure. There’s a risk of failure. There’s a whole host of reasons, but I’d say the number one is economics.

Q: How can conservation farming become more economically viable?

A: Conservation is not free. Initially, somebody’s got to pay for it, and I’m not sure it should all be on the farmer. If we would get paid for carbon sequestration that would certainly help.

But until then, there’s cost share programs from places like the (U.S. Department of Agriculture) and (Natural Resources Conservation Service). There’s several other places that will offer cost share. A lot of the big food companies now are getting on board, because they want to be able to tell their customers that their food supply is grown sustainably, so they’re offering some incentives to farmers.

So there are some sources of revenue, but it’s not a huge amount of money. Over the long run, I think this way of farming will eventually be self-sufficient. In other words, the benefits will outweigh the costs, and there won’t be a cost to it. Hopefully, it will become the mainstream way of farming.