Courtesy of Rosario Benavides

Courtesy of Rosario Benavides

In 2019, I read “The Culture Map” by Erin Meyer. The book came to me as an assignment from my boss at the time. We were building a team to take on global climate action with people from different countries, developing projects across five continents. Cultural diversity was intrinsic to our day to day work, and my boss was embarking us on a journey to better understand how to navigate it.

In her book, Meyer identifies eight scales that she believes are critical to understand when working with different cultures: communication, evaluation, persuasion, leading, decision-making, trusting, disagreeing, and scheduling. According to Meyer, the interplay of these scales creates a culture’s map, and understanding where each culture lands on each of these scales helps us engage more effectively with others.

Reading this book was eye-opening. Suddenly, all the challenges we faced in our global team began to make sense.

I have been reflecting on these ideas a lot lately. In the lead-up to and during last November’s COP29, or the Conference of the Parties of the United Nations Climate Change Conference, I found myself thinking how Meyer’s culture map might translate into international climate negotiation space. What role do cultural differences play when nearly 200 parties come together to address one of the most pressing global challenges of our time?

Negotiations on climate finance took center stage at the recent COP29. The Conference of the Parties faced high expectations regarding the New Collective Quantified Goal, with tension between developed and developing countries over the target amount, who should contribute, and the mechanisms for doing so.

In the end, delegations in Baku agreed to a goal of $300 billion annually by 2035. This target triples the previous $100 billion goal but falls significantly short of the $1 trillion developing countries were advocating for. The results have significant implications, given the direct relationship between countries’ ambitions and the availability of financial resources.

From 11,400 km (7,083 mi) away, I followed the negotiations in Baku, Azerbaijan, captivated by the tensions between developing and developed countries over climate finance. It reminded me that I was able to experience a glimpse of these tensions in an entirely different setting.

One afternoon, during a discussion about the Quantified Goal in my climate finance class — a culturally diverse classroom — I witnessed 18 of us each wanting a different outcome, and I couldn’t stop thinking about this challenge for negotiators. Beyond identifying a way to reach consensus on complex issues, negotiators must navigate a room filled with representatives from nearly 200 different cultures.

It struck me that Meyer’s cultural scales could be just as relevant in climate negotiations as they are in business contexts. In particular, one question kept popping into my mind: How do different approaches to trust influence the outcomes of global climate agreements?

Driven by The Culture Map and a series of life events that deepened my love for multicultural spaces, I decided to take a class on building trust across cultures during my master’s program. This class was taught by professor Jacqueline (Jacqui) Oliveira, a leading expert in intercultural communication and trust-building, with more than 30 years of experience as an intercultural consultant. Intrigued by the intersection of trust and culture, I met with her to ask her some questions about the role trust could have in international climate negotiations.

Jacqui began working on intercultural trust in 2010 when she started asking clients what they needed for their multicultural business ventures to thrive. She recalls how the word “trust” kept coming up in their responses and said: “I started asking, ‘and what does that (trust) look like?’… and that’s where culture was really magnified, because what looked like trustworthy behavior in one culture can look completely the opposite in another culture.”

Despite the varied expressions of trust across different cultures, Jacqui emphasized its universal importance: “Trust is ubiquitous. I have never met a culture that says we don’t need trust,” and continued: “…if you want things to happen, if you want people to be open to sharing information, to not withhold information, to be open about maybe a mistake that was made, be open about questioning authority. If you want that, you have to have trust.”

“(Trust is) essential!” Jacqui said in exclamation, adding, “Intercultural communication, intercultural trust will tackle global challenges.”

Author Meyer identifies communication styles as one of the eight crucial scales to understand when dealing with different cultures. For Jacqui, this is especially important in settings like international negotiations: “With regard to the many parties … communication styles are really different, and this is really important.”

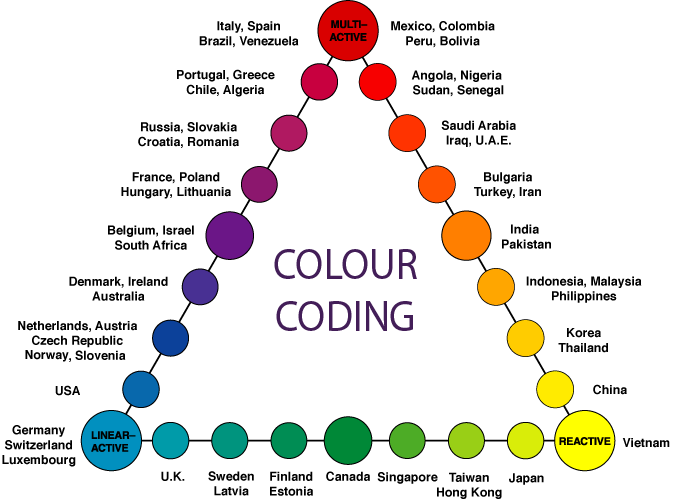

She highlighted three different communication styles that are strongly influenced by culture: Linear-active, multiactive, and reactive communication styles. She also emphasized how non-verbal cues can convey a depth of information.

As explained by Jacqui in her class, linguist Richard Lewis defines these three communication styles as what he calls The Lewis Model:

During our conversation, Jacqui and I recalled something we had studied in her class – what she called the three golden rules to build trust across cultures. The first rule is to know yourself, the second one is to be curious to understand culture, yours and others, and the third is to be open to change.

It’s important for professionals in international climate negotiation spaces to know themselves and their own culture.

“Be mindful of your own biases and that includes good biases or bad biases,” Jacqui said. “Be involved with people who have a different mindset than yours. Know what you’re walking into. Learn. Learn about them, and be open to change.”

Global climate negotiations can feel very distant for those who are not participating in them. I asked Jacqui what actions individuals can take, from a trust-building perspective, to contribute to a world more resilient and collaborative in addressing global challenges.

“I think what every person on the planet can do, is really what Victor Franckl said,” she said.

“…There are three ways that people responded to the horrors of the Holocaust. Some people responded as victims – How could this happen to me? How could this be?” Jacqui said. “Some people responded as what he called Capos, which is, you align yourself with the one in power. You become friends with it … And the third kind, he said, is the one who really understood what their purpose was.”

She continued with two practical and challenging pieces of advice:

“Talk. Talk to the people that you hate the most, which is so hard to do, but if you have a mindset of saving the planet …That will change who’s on your team.”

“Everybody has something special. And (Frankl’s) point was: Know what you have, learn what your purpose is, and live it.”