The Cascade red fox. (Courtesy of J. Kuehlman)

The Cascade red fox. (Courtesy of J. Kuehlman)

Good day! I am Alisa, I am an enrolled citizen of Skokomish Indian Tribe. I come from a family that was born and raised on the shores of Tuwaduq. I personally grew up living on the “other side” of the river and spent my childhood walking the rez (reservation) before there were sidewalks, laughing and playing with cousins. While growing up I was blessed to have family that valued traditional ecological knowledge, also known as TEK.

I was taught the basics – take care of your elders, listen with your heart and act in a humble manner. I was taken to many elders’ homes, where we delivered salmon and deer to feed their souls and would sit for hours, listening to old drinking stories set in a time where cement roads did not exist. My favorite stories were those that described a time when you could smell and taste the mornings as the sun rose up into the sky.

These ways have followed me through out my life. I have incorporated as much as I could, teaching my kids what I had learned while trying to leave my tiny home and attend college(s) only to fail several times. The lessons I was ingrained with always seemed to conflict with what I was being taught and caused an internal fight within myself. This continued until I was in my 30’s when I started attending a tiny TCU Northwest Indian College (NWIC). I started here to get an education and to become better for my foster baby that I had just received into my care. I wanted to make sure that my ignorance did not hinder him and would give him a better path to follow.

While attending NWIC I decided that I wanted to be a teacher and work with kids, but the more classes I took, the more I was encouraged to go back to my roots. I found myself relearning and reclaiming our language, teaching two toddlers to speak their Indigenous language first before English for a better understanding of their indigeneity.

I started taking my now two foster babies into the woods to gather, taste and feel the earth.

Striking my interest in science, this is where I came into contact with the Cascade red fox. At a meeting being held between the local Tribe and Mt. Rainier National Park, a tall woman asked me what I knew about language and animals. My response was, “not a whole lot” but was intrigued as to what she was leading to.

So I was off in the corner with her talking for a bit where she also asked me if I had ever hear any stories of coyote and fox, and I snickered and said, “Yeah those exist.” She then talked to me about this elusive Indigenous fox only found in the Cascade range that seemed to be disappearing from the area. At this time only a handful of people had studied it and had only studied in a linear manner. So I agreed that I would take an extra year in the bachelor’s program to study this fox.

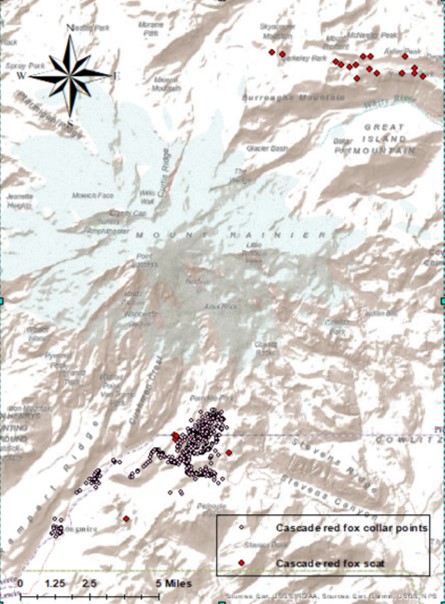

Despite many twists and turns, and a pandemic, I was lucky to have participated in an internship through Salish Sea Research Center and NASA, where I was able to learn GIS and incorporate Western tools with Storyworks to learn more about this fox. Others were collecting scat samples through citizen science and taking pictures of them in the majestic wilderness of Teqwuma where I was personally able to take the data and create maps. I was also able to search archives, looking and listening to stories that incorporated this trickster fox and coyote, who seemed to share roles in food and fire, constantly tricking each other.

Today the Cascade red fox has moved up from being considered an imperiled species, to an endangered species. I hope that my work in helping to form a bigger, fuller, more holistic picture of this beautiful creature has helped in changing this classification. I hope that my voice on advocating for collaborations with local Indigenous communities is heard and validated as knowledge and not just stories or knowledge that can be bypassed or used to build careers.

Having this relationship can open up a better understanding of the world around us, giving a longer historical account for everything Mother Earth has for us. Thank you for your time, hoyt labcebut, take care and see you later.