Jeremy Kohler

Jeremy Kohler

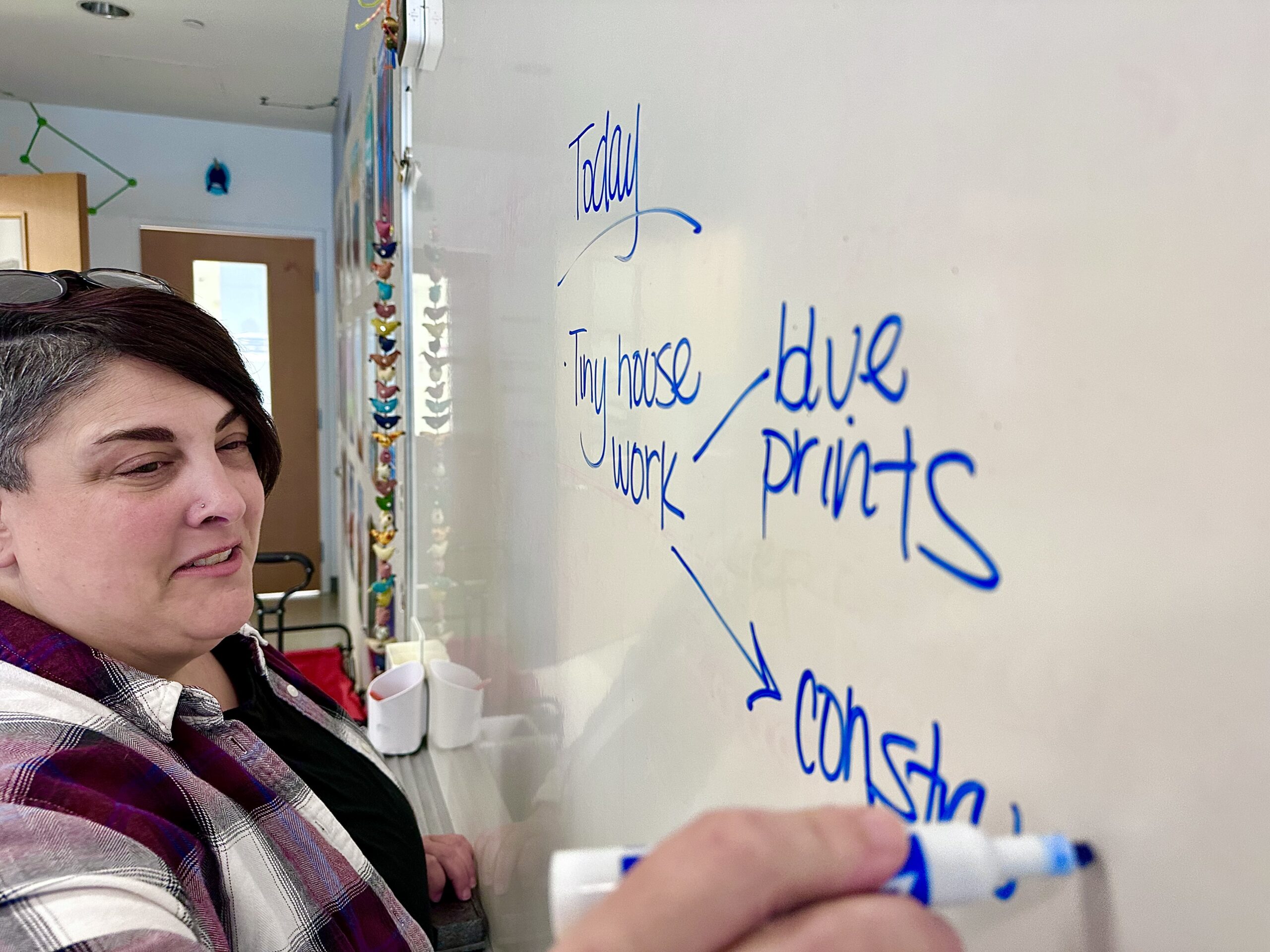

As their lunch period came to an end, 15 students made their way into the science classroom at the corner of the fourth floor, grabbing large white trays from the lab tables in the back, each holding a sharpie, a ruler, a poster board, a cardboard cutter, and a blueprint.

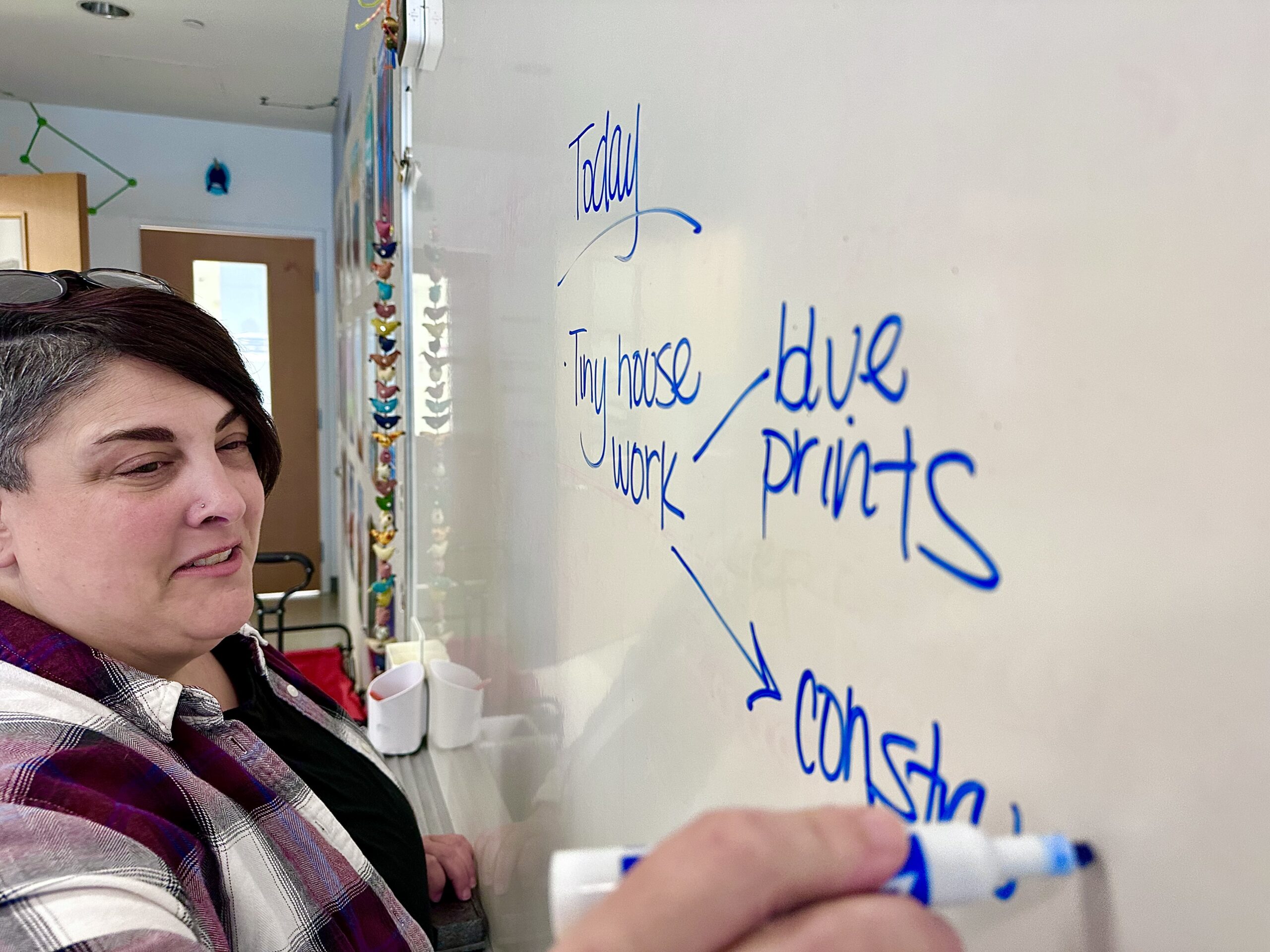

Amy Cataldo’s seventh-grade class at the Edmund Burke School in Washington D.C.’s Ward 3 is building tiny houses. Well, models of tiny houses.

Cataldo gave each group a hypothetical $15,000 budget, a location in the U.S., a family to house, and exactly 240 square feet to work with, with just one catch: It had to be fully sustainable and able to adapt to the climate challenges of their specific area.

“Right now we are working on building houses that are, like, small houses, in really climate active places,” said 12 – “almost 13” – year-old Sana. “And the challenge is to make our house as sustainable as possible.”

Sana’s group excitedly finished the blueprint for their tiny home in Maui, Hawai’i, featuring an outdoor pineapple garden, a compostable toilet, a solar paneled roof, and recycled driftwood floors. And the group has an extra advantage because they can ride their bikes everywhere, Sana happily explained – after all, their house is less than a quarter of a mile away from the Maui city center, she boasted.

4,762 miles east of Maui, E.C.’s group is working to build a tiny home that will be resilient to the over 100 inches of snow that falls on Syracuse, New York each year. How? Solar panels, a heating system, a $76 couch from Amazon, and a barn for the backyard.

“We found a barn for $466,” his classmate said. “We’re not sure if that’s a scam.”

“It doesn’t matter,” E.C. interjected.

Another group worked on a house built from a shipping container, designed to withstand the unpredictable weather of southern California, and the last group began assembling the walls of their tiny house as two of its members debated whether a one foot-wide door would be large enough. They decided it probably would be.

“Across the U.S., they’re tackling different climate issues,” Cataldo said. “They’re realizing what their ‘client’ is going to need to make it functional.”

As she explained, the tiny house project is just one small part of a science curriculum built around climate justice. Throughout their seventh-grade year, students at Burke, in all of their classes, learn about the intersections of sustainability and social justice, as well as themselves and the worlds around them.

At the front of her classroom, which she helped architects design when the school decided to expand and construct an additional building in 2003, Cataldo sits at a desk, iPad in hand, calling students to the front to review a test from the week before. A trio of tattoos is visible on her forearms, owing to the rolled up red flannel she has donned for the day. She occasionally brushes her short hair out of her eyes, and her sandals remain firmly planted to the floor beneath her.

She has been teaching science at Burke for 22 years and comes from a long line of educators: her mother, father, two siblings, in-laws, and a healthy portion of her cousins all work in education. Both of her children also attended Burke, one of them a recent graduate and the other a current high school senior.

The “family affair” at Burke has also become an important part of her love for teaching at the private school in D.C.’s Van Ness neighborhood. As she explained, being with students from the moment they start their first day of sixth grade to their graduations at the end of their senior years provides her with an unmatchable opportunity to watch them grow from children to adults.

“Truly, it’s one of my favorite things ever,” Cataldo said.

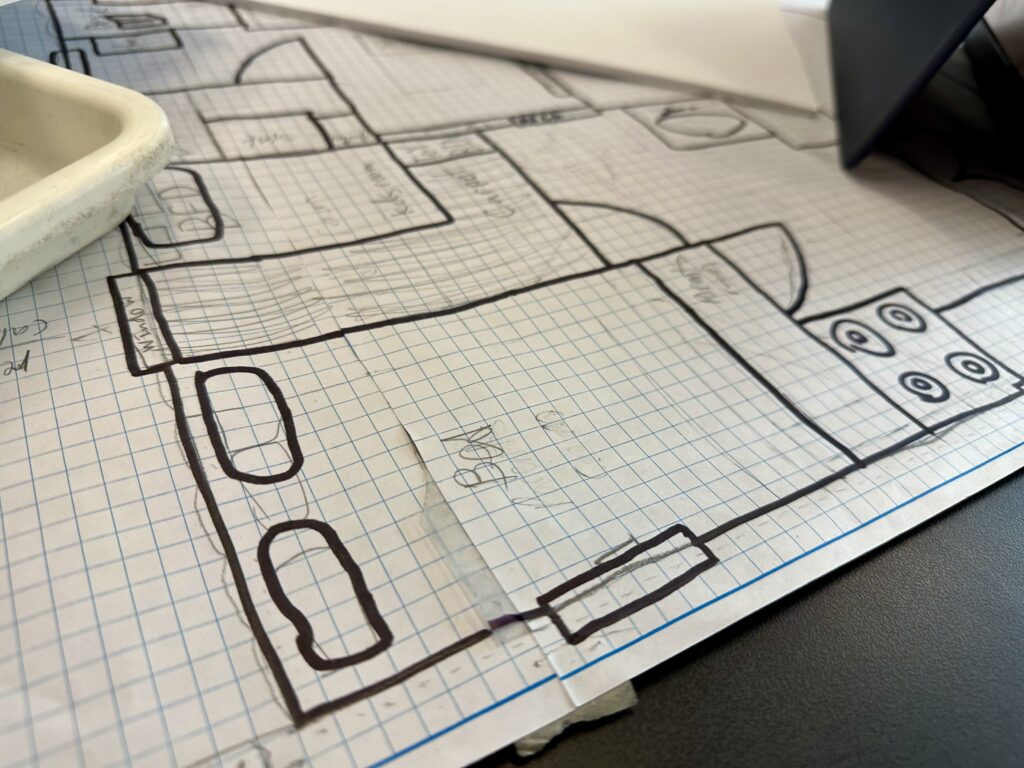

The Edmund Burke School opened its doors in 1968 to 17 students. In the 55 years since then, the school has become home to 315 students, ranging in age from 11 to 18 years old (or 6th grade through 12th grade). Since its founding, Burke has placed heavy emphasis on a progressive education: Classes are small, teachers and students are all on a first name basis, and students are given a significant amount of independence, both in their studies and in their school days.

As part of the school’s commitment to equity and social justice-oriented education, each grade level spends the year learning through the lens of a particular social justice issue: Seventh-graders focus on the climate; eighth-graders focus on civil rights; sophomores focus on a “soapbox project,” where students do a deep dive into a certain issue of their choosing; and seniors are encouraged to bring all of the themes they learn about together with a capstone project.

And, as Cataldo explained, the justice-oriented curriculum at Burke has led many students to careers in social justice-related fields.

“A lot of our kids go on to do nonprofit work and things of that nature,” she said. “It’s pretty amazing.”

A Burke education is also highlighted by frequent field trips related to the topics students are studying, with some going as far as New York, Pennsylvania, and Alabama. The trips are designed to reinforce the themes students learn about, and are almost always paid for entirely by the school. This year, the seventh graders at Burke are taking a trip to Philadelphia as part of a year-long comparative project between sustainability practices in Pennsylvania’s largest city and those in D.C.

This approach, providing students with opportunities to understand how climate change affects them at home and seeing which sustainability practices work and don’t work, is a key element of effective climate education, according to University of Florida researcher Martha C. Monroe.

A study conducted by a team of researchers led by Monroe found that students resonated the most with climate education frameworks that: Were built around their own personal experiences; encouraged students to engage with one another through discussion and debate; utilized models, visuals, data collection and analysis; and created a space where students were able to freely ask questions, promoting a system of lasting education.

D.C.-area high school science teacher Daniela Munoz couldn’t agree more.

“Given the urgency of the issue, I do think that it is a disservice to approach it in a way that doesn’t really drive that critical thinking piece,” Munoz said. “We don’t tell our students what to think, but once they analyze the data…it’s a very innate human reaction to think ‘okay, so what are we going to do about this?’”

In Cataldo’s seventh-grade class at Burke, that data driven approach is already one that students have fully embraced. As they completed the blueprints for their tiny houses, they continuously raised questions about sea levels, precipitation rates, and constantly rising average temperatures across the country.

But the students were also quickly realizing just how expensive it is to combat some of the world’s most pressing climate issues.

Sana’s group had hoped to install energy-friendly roof tiles, but the recycled wood, locally-sourced wall paneling, and solar panels had all but dried up their $15,000 budget. If they wanted their sustainable roof, they would likely have to give up their sustainable energy supply. And if they gave up their sustainable energy supply, they would have to give up their fully electric kitchen.

Sana was realizing just how difficult it could be to live a sustainable lifestyle, especially with limited resources.

“[It] makes it kind of hard to be sustainable if you don’t have access to as much money,” she said. “It was like $20,000 for a fully sustainable roof.”

While Sana’s group eventually settled on going without the energy-efficient roof, their debate still acts as a sort of microcosm for one of the largest barriers to both sustainable life practices and effective climate education: access.

And robust, climate justice-centered educations, like the one at Burke, are not available to every student. With a price tag approaching $50,000 per academic year, Burke, like many private schools with similar approaches to education, may not be attainable to many families. And climate justice, like so many other urgent initiatives, is one that requires enormous amounts of funding.

But the Edmund Burke School is not unaware of the concerns that may come from its lofty cost of attendance. This year alone, Burke allocated $2.3 million to financial aid, ultimately awarding an average of $20,000 in need-based scholarships to a third of its students. And the school hopes that, with a Burke education, its students will continue to create change for those who need it most in their communities.

Cataldo said that Burke’s approach to education was a large reason she wanted to focus so heavily on teaching her students about climate change and its impacts on communities around the world.

“For us, it really is part of our mission. It’s really about getting kids to understand who they are,” she said. “It’s more than just climate, but for everyone to realize that we’re all different from one another, but we can learn so much from one another.”

As Cataldo’s class loaded their blueprints back into their trays, searched for a couple loose sharpies, and began to gather their bookbags, she reminded them all about their field trip to IKEA the next day to get some final supplies and inspirations for the furniture and decor in their tiny houses. She let them all know that their lunch would be paid for, and said they wouldn’t regret trying some Swedish meatballs.

One student raised his hand and asked if he could bring some extra cash in case he wanted something from the store that the school wouldn’t be paying for.

Cataldo responded quickly. She explained the importance of equity, telling the class that it was important to both her and the school that no student feels left out or left behind by their classmates, and this was one of the ways they could ensure that wouldn’t happen. He nodded in understanding, and a few of the students chimed in with their agreement. Then the class period came to an end, and Cataldo started gathering what she would need for her trip to Spencerville to coach the middle school girls basketball team.

The science lab on the corner of the fourth floor would be empty for the rest of the day. The girls basketball team would win their game against Spencerville Adventist.

And the tiny houses serve as a tiny reminder that climate justice begins in classes like Amy Cataldo’s.