Sara Cottle/Unsplash

Sara Cottle/Unsplash

As another hot D.C. summer encroaches, the 19,000 people living near Rock Creek will need to find a way to cool off — but not in the water.

While the waters may look idyllic, a century-old sewage system and dangerously high levels of bacteria have made the urban national park unswimmable for decades. Now, a team of volunteers is working to change that, one water sample at a time.

D.C. residents know that swimming in the city’s waterways is not the best idea — in fact, it’s been illegal since 1971. Lorde shocked concert goers and made national news last year when she claimed to float in the Potomac before her show. There’s a stigma around the cleanliness of these rivers from decades of pollution, but in recent years, the waterways have been slowly improving.

The Environmental Protection Agency has been trying to make the city’s waterways swimmable and fishable since the Clean Water Act of 1972. While the original ten-year timeline for that goal passed forty years ago, the act set in motion a clean water agenda the city is hoping to reach in the next few years.

In 2019, city officials began floating the idea of relaxing or lifting the swim ban. But even after decades of cleaning up the waterways, environmentalists question whether the water is safe enough to open to public swimming. Data from the D.C. Volunteer Water Quality Monitoring Project is helping shed light on the state of the city’s rivers and streams.

On a cool day in early May, the ground is damp and the water is high in Rock Creek Park. It’s the first day of the 2023 water monitoring season, an overcast morning after several days of on-and-off rain.

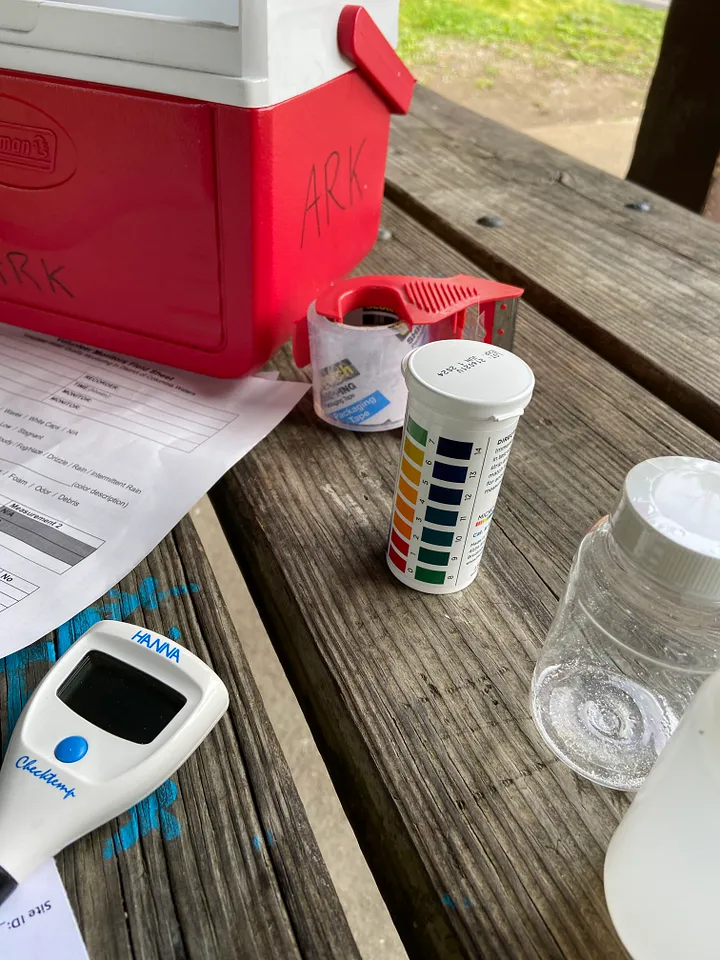

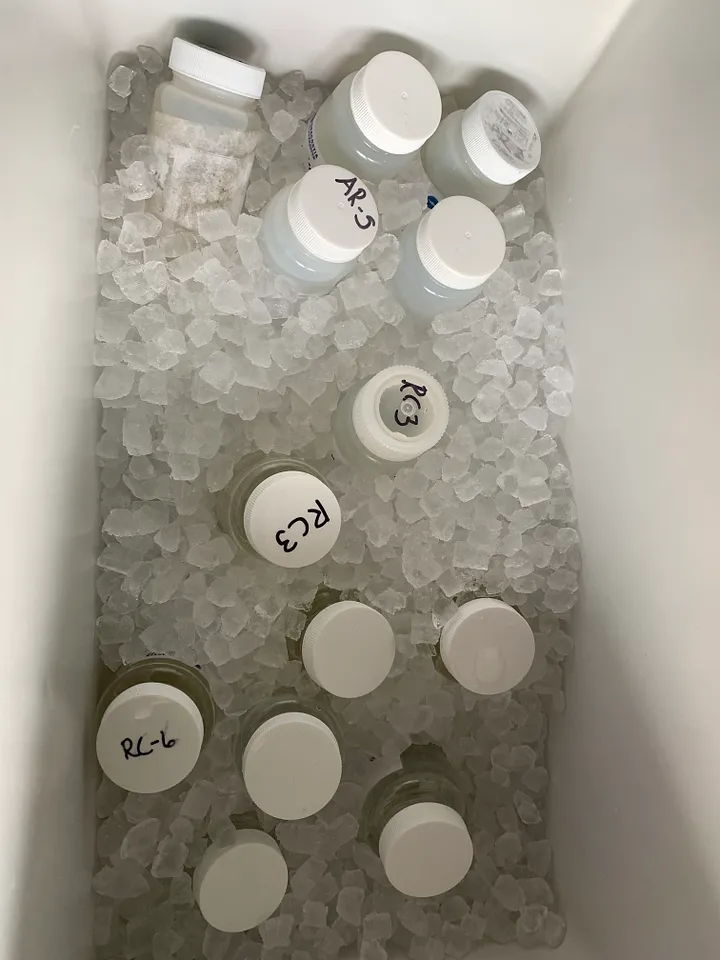

Landrum Beard, Community Engagement Coordinator at Rock Creek Conservancy, sits under a picnic pavilion at a table lined with small red coolers for volunteers to pick up with their water testing kits. They’ll head out toward their assigned sites, marked with ribbons, along the creek and return with the coolers filled with water samples, which are taken to Anacostia Riverkeeper’s lab for testing.

Anacostia Riverkeeper launched the D.C. Volunteer Water Quality Monitoring Project in 2018 to measure and track contamination levels in D.C.’s main waterways: the Anacostia River, the Potomac River, and Rock Creek.

With a $140,000 grant from the D.C. Department of Energy and Environment, the project has grown into a collaboration between Anacostia Riverkeeper, Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay, Rock Creek Conservancy, and Nature Forward. The groups have trained almost 400 volunteers from all eight wards of the city, collecting more than 2,000 water samples from 2019 to 2022.

Each Wednesday morning from May to September — considered the outdoor recreational season — teams of volunteers take water samples at two dozen sites across the city and test for pH balance, E. coli levels, water temperature, air temperature, and turbidity, a measure of water clarity. They also note if they see anyone in the water, as many people and their pets still wade in the creek despite park signs warning against it. The results are posted each Friday and updated in the Swim Guide app, which lets users check the water quality of nearby beaches.

Most of the volunteers are consistent, Beard says. There are some newcomers on this first day of the new season, but others have been a part of the program for years.

Benita Veskimets is one of those veteran volunteers. Veskimets, who used to work in fundraising for Rock Creek Conservancy, is in her fourth year of water sampling. “I’m really curious to see what happens this year,” she says. “Last year, I feel like it was worse than the year before.”

Only a few of the Rock Creek sites passed with safe bacteria levels last year, Beard confirms. Those were mostly on dry weeks, when there was little or no rainfall impacting the stormwater sewage overflow. This morning is not one of those times. After a rainy week, the creek is likely swimming with bacteria from runoff. Not the best way to kick off the season, he admits.

The root of this problem lies with infrastructure, and if you’ve ever walked through Rock Creek Park after a rainstorm, you can smell why.

After just half an inch of rainfall, hazardous waste and sewage flood into the creek from the city’s old combined sewer infrastructure. In this system, stormwater and sewage flow through the same pipes — and when it rains, they quickly fill up and overflow into the rivers. Rock Creek is considered dangerously contaminated when that happens, and recreators are advised to avoid the waterway for up to three days afterward.

Volunteers have tracked that trend at the sampling areas. “All these sites, for the most part, have a storm drain a few hundred feet or so upstream from where the sampling site is,” Beard said. “So after big rain events, we always see that the sites have extremely high bacteria.”

D.C. Water is now working on a $2.6 billion overhaul to the city’s sewage system with the goal of redirecting some of these sewage lines away from the city’s waterways and back toward treatment plants. This plan, the Clean River Project, is set to be completed in 2030.

In the current phase of the project, the National Park Service is teaming up with D.C. Water to take on Piney Branch Creek, one of Rock Creek’s main tributaries and victims of contamination. An estimated 39 million gallons of sewage and stormwater pour into the creek each year.

“The way to do it is to build bigger pipes under the ground that can handle all the sewage and the stormwater and keep it in the pipes and get it down to the treatment plant,” said Steve Dryden, a local conservationist who has worked in the Piney Branch area for years.

The city is expanding these pipes, aiming to reduce the amount of sewage flowing into the three waterways by 96 percent. It’s part of a hybrid plan for Rock Creek that includes both traditional “grey infrastructure” — like basins, drains, and pipes — and new “green infrastructure,” such as rain gardens and permeable pavers in 365 acres of the surrounding urban areas. A pilot program for this green infrastructure plan reduced runoff into the creek by nearly one fifth, surpassing D.C. Water’s goals.

But sewage overflow and runoff after rainfall is not the only contamination source in Rock Creek. The water quality monitoring project reports that some sites have had persistently high levels of bacteria even during dry weather, which may be caused by “outdated infrastructure, leaking sewer pipes, or uninvestigated point-source pollution.”

Jeanne Braha, executive director of Rock Creek Conservancy, said this may also come from pet waste and houses or businesses with sewer pipes that are accidentally hooked up to storm drain pipes that flow into the creek. Construction in the urban area is another contributor, Veskimets adds. While the Potomac and Anacostia bacteria levels are a direct result of combined sewer overflows, Rock Creek’s contamination comes from several sources — making solutions harder to find.

While solving Rock Creek’s water contamination problem is a long process, participants in the D.C. Volunteer Water Quality Monitoring Project are ensuring that city officials and environmentalists have the data to help.

The Potomac and Anacostia rivers have been slowly improving in water quality since the Anacostia was once dubbed “one of the most polluted waterways in the nation.” People debate whether the rivers have recovered enough to be swimmable.

“I think we’re getting there,” said Louis Eby, a longtime water quality volunteer and former Attorney Advisor in the EPA’s Office of Water. He’s seen a lot of progress in the two rivers, but remains cautious about Rock Creek.

“I wouldn’t swim in Rock Creek,” he said. “We’ll get there some day for Rock Creek, but not soon.”

Sure enough, the rain in early May was a forecast of remaining challenges. Both upper and lower Rock Creek sites reported unsafe E. coli and pH levels in the first week of monitoring.

Still, citizen scientists will continue to keep tabs on the water quality each week. As soon as Rock Creek is finally swimmable, they’ll be the first to know.

As the summer recreation season kicks off, people flock to D.C.’s waterways for kayaking, paddleboarding, and sightseeing — and one day soon, they might be able to safely swim in them.