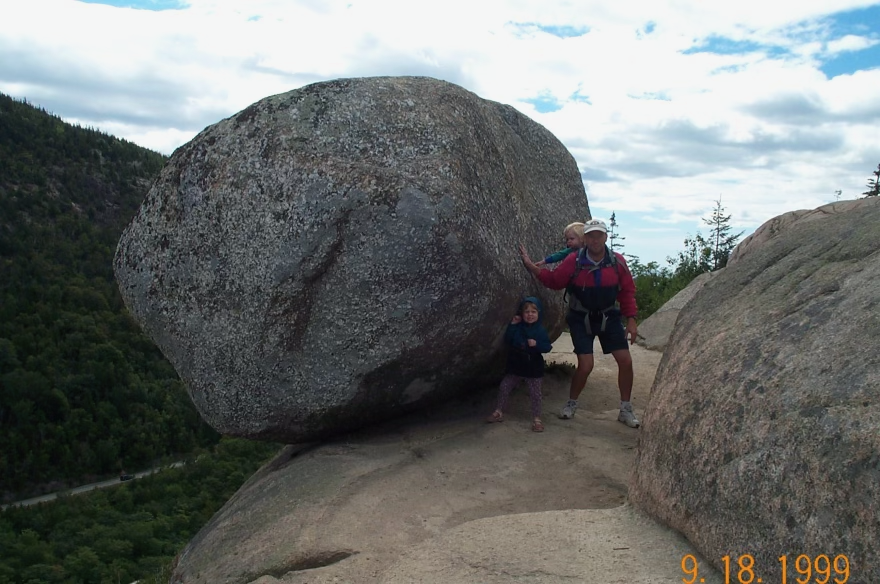

(Courtesy of Kristen Caldwell)

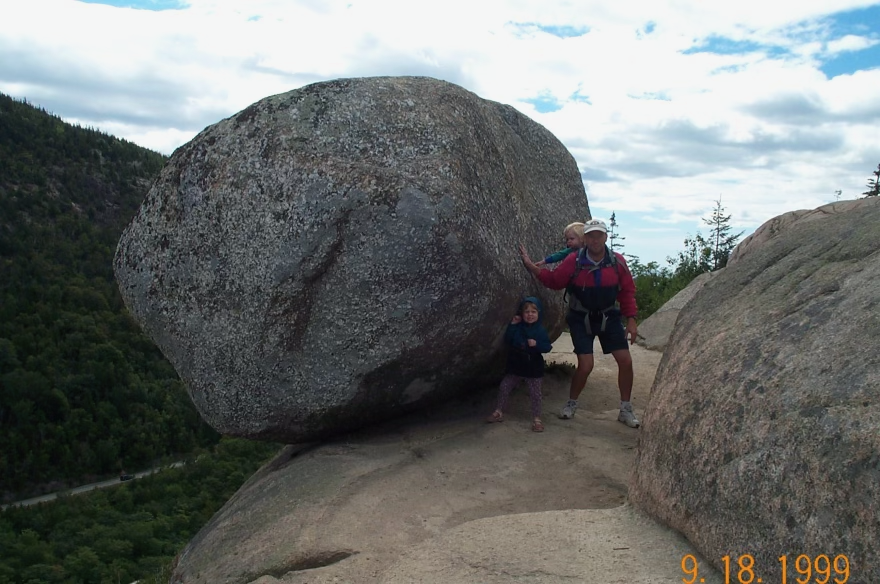

(Courtesy of Kristen Caldwell)

“Race you to the top!” my sister yells at me as we run up the Bubble Rock trail in Maine’s Acadia National Park. This trail leads us to an iconic summit featuring a gravity-defying boulder positioned on the side of a mountain, looking like it could fall at any moment. At age 5, I would throw all of my body weight onto the boulder in an attempt to push it off the mountain.

The trails that guide us around Acadia on our family vacations have been in use for thousands of years before us as legacy trails. Instead of being used for recreation, legacy trails brought ranchers, Indigenous peoples, or firefighters from point A to point B as quickly as possible, long before the times of cars and paved roads.

Acadia now hosts about 4 million visitors each year. On trend with many other National Parks across the country, visitation soared after the pandemic. I was first thrilled to hear that many other Americans are taking advantage of their public lands. However, calls from the parks rang a different tone. This rapid increase in visitor use has strained infrastructure systems, spread already overworked staff thin, and battered hiking trails.

Times like these are when the work of recreation ecologists shines through. Jeffrey Marion, Ph.D., is a recreation ecologist with the US Geological Survey out of Virginia Tech and studies how the history of legacy trails shape the sustainability, design, and durability of our current hiking trails across the country. Marion’s goal is to better understand how to mitigate the impact that humans have on the environment while allowing them a taste of wilderness through hiking trails.

Hiking trail design is oftentimes hidden on the paths that I grew up on. Once trail designers and builders have completed their trail, it often should appear as if they were never there to give visitors a taste of “untouched” wilderness. Careful planning is critical in ensuring that a hiking trail is long lasting. This careful planning may often be contrary to the legacy trails that already lie in place—these were built for convenience, not sustainability.

After analyzing the legacy trails in an area, designers must assess if they are already sustainable, can be altered, or must be scrapped all together. Marion emphasizes that water plays the biggest role in a trail’s sustainability. If you were to dump your water bottle down a mountain, the water would take the fall line down to the bottom. If a hiking trail follows that same route or lies at an unfriendly angle to it, water will either wash out or puddle in the trail.

According to Marion, the ideal trail angle is one that is diagonal to the fall line. In the process of trail design, designers then carefully craft the control points of a trail. These points lay out where the trail needs to begin and end, where people should go, and where people shouldn’t go. In the case of Bubble Rock, the iconic viewpoint that makes the hike is a positive control point. Other examples of positive control points include waterfalls or scenic vistas, any beautiful scenery that humans would stray off the path to see if the trail did not already lead them there. Negative control points such as ecologically sensitive sites are used to mark areas that the trail needs to avoid.

Marion says that trail design is not rocket science—it’s just a general understanding of the ecological role that outdoor recreationists have on their environment. With all of the steps that go into the design process, trails reemerge as more sustainable and durable to the effects of high foot traffic and natural elements. Sustainably built hiking trails mitigate the effects that outdoor recreationists have on their environment while giving them the feeling of being in total wilderness.

With the recent surges in park visitation since the pandemic, recreation ecologists suggest that relying only on sustainable hiking trails isn’t enough. In 2020, visitation records were up 335% in July in comparison to May visitation numbers—this figure historically lies at 75%.

Christopher Monz, Ph.D., a professor of recreation resource management at Utah State University, explains that visitor management is also key in mitigating the impacts that overcrowding has on hiking trails. He researches visitor impacts in Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado, the fifth most visited park in 2020. To reduce overcrowding, Rocky Mountain National Park implemented a timed-entry system into the park. Visitors cannot get into the park without a reserved spot at a specific time.

Monz says that timed-entry systems help reduce the burden of overcrowding on park resources while improving overall visitor satisfaction. Some have suggested that extending access into the backcountry areas could alleviate overcrowding, however this raises questions about whether parks exist to serve visitors or the environments they protect. To Monz, the future of managing overcrowding in America’s public lands looks like combining sustainable hiking trail design with managed access into the park.

Behind my family’s hikes in Acadia were trail designers working to ensure that we had the ability to hike to Bubble Rock without harming the native plants, animals, and soil. After learning about how sustainable trail design and visitor management can reduce the impacts of overcrowding, I no longer just see hiking trails as the pristine nature that I once did. I now see the trail designer studying topographic maps to find the best route or the trail crews moving rocks, building stairs, or clearing trees to make a trail passable.

In a way, hiking trails are more beautiful now. I see the future of high visitation in National Parks as a mesh between human impact and natural beauty. We can still preserve our public lands, make hiking trails more durable, and allow access for visitors all while protecting the core environment of parks. It’s something we rarely see in today’s world—a relationship that strikes the perfect balance of human impact and protection to let people appreciate nature while preserving it for generations to come.