Envisioning an inspiring future requires the right vocabulary to build this world — the upcoming "Loanwords to Live With" is a collection of ecotopian words that should exist in English to talk about the environment, but don't yet.

New words to talk about the future: ‘Loanwords to Live With’

The words we use create meaning and make sense of the world around us. Language culturally constructs our perceptions, and the overarching language used to talk about climate change is negative. The apocalyptic predictions that scientists give for the 21st century and beyond provide us with a vocabulary of trepidation, disaster, fear, and ultimately paralysis about the coming challenges. Changing the way we speak about climate change means acquiring new and different words.

Besides switching our vocabularies and our mindsets to more positive connotations in our own language, there are certain concepts and terms nonexistent in the English language that would aid in our envisioning of a better future.

Published later this year, the collection Loanwords to Live With: An Ecotopian Lexicon Against the Anthropocene seeks to assemble a disparate lexicon that describes “not what exists in fossil-fueled capitalism but what should be: ecological terms and phrases that intimate and inspire better ways of life.” Ecotopian language in the Anglosphere pits mankind as separate from nature, deepening the divide between us and the environment. Reaching beyond English and the dominant narrative of humans triumphing over the elements, we provide here a list of 6 words or terms of potential topics in the collection to reinvent how we talk about climate change and our relationship to the rest of life in the ecological web.

1. Nahual

In Ancient Mayan mythology, each person was believed to have a companion animal that shared their soul and fate – as such, human and nature were intimately connected. The relationship between a person and their nahual is described like wearing a mask: one hides behind the other. The quetzal, Guatemala’s national bird, was said to be the nahual of a Mayan prince who fought the Spanish conquistadors. When the prince was felled by a Spanish spear, the quetzal which was circling overhead in protection, flew down and landed upon the prince’s wound, dipping its breast feathers in his blood – this is why the breast feathers of the quetzal are said to be a fiery red.

Your nahual is assigned to you at birth, and similar to a zodiac, influences one’s character traits.

2. Empath

The term empath is borrowed from science fiction writing, most notably from Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower which is a hopeful tale set in a dystopian United States. An empath is a person with paranormal ability to perceive the mental or emotional state of another individual. Butler’s protagonist in this novel became a “sharer” or empathy because her mother took a drug while pregnant. The protagonist shares the pain of all those living around her, and the connection she has to the rest of the world through compassion and empathy, rather than selfishness, become the guiding principles to a new society that the protagonist founds. Empathy and sympathy are central to the concept of universal humanity, and nurturing our capacities to be empaths, or emotional sponges, from a young age, will allow us to engrave the importance of other life (human and non-human) into our consciousness.

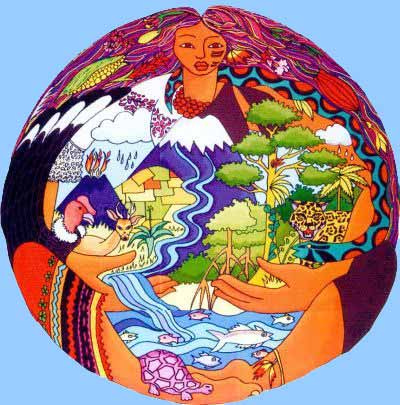

3. Pachamama (and other earth gods/goddesses)

Pachamama is an earth goddess of the Andes Mountains who survived the Spanish conquest and is still revered today. In Incan mythology, Pachamama presides over planting and harvesting and has the power to embody mountains or shake the earth. In English, Pachamama most closely means Mother Earth. Pacha means earth, cosmos, universe, time, space etc. in Quechua and Aymara, and Mama means Mother. The deity is claimed to be the origin of the elements of the world as we know it – the four cosmological Quechua principles of Water, Earth, Moon, and Sun come from Pachamama. The relationship to Pachamama is visible to this day in the practice of challa, or the sprinkling of drops of beer/alcohol on the ground before drinking as a way to give thanks to Pachamama.

The veneration of earth deities is most common in places where people are more closely bound to the cultivation of their own livelihoods and sustenance. As more of the world’s population continues to move into cities, we must not forget importance of balance in nature. In South America, many believe that problems arise when too much is taken from nature because they are taking too much from Pachamama.

4. Forest bath (森林浴)

The longevity of the Japanese may be tied to their practice of “forest bathing,” or essentially meditation in nature. There’s no water involved in this bath. It is rather a submerging of oneself into the elements of nature; quality time in the forest without distractions. The practice of Shinrin-yoku was part of a national public health program introduced in 1982 when the forestry ministry coined the term. Since then, there has been proof of beneficial health effects. The magical, rejuvenating boost that a walk in the woods gives you is rooted in naturally produced allelochemic substances known as phytoncides, or pheromones for plants. When humans are around these phytoncides, they help to decrease blood pressure, alleviate stress, and strengthen the immune system. Garlic, onion, pine, tea plants, and oak trees give off phytoncides (and that’s also why they are so aromatic!).

5. Heyiya-if, from Ursula Le Guin’s Always Coming Home

Famous sci-fi author Ursula Le Guin integrates Taoist beliefs into a cultural group called the Kesh in her book, Always Coming Home. The Kesh are a peaceful people who reject domination over nature. The double spiral of the Heyiya-if is a holy symbol for the Kesh. It resembles the taijitu, or the ancient symbol of yin yang. The swirling motion of the Heyiya-if describes the divine circle of life. Its endless movement represents the constant change of the world and its cycles, where night becomes day which turns into night again; all births culminate in death, which leads to a re-birth. The opposing but complementary forces present in everything show how our own life cycles are interconnected and dependent on the natural world. When our lives and fates are intertwined with the rest of nature, we cannot exist separately.

6. Buen Vivir

.jpg)

Buen vivir literally means a good life or well-being, but it also encompasses a social philosophy inspiring movements in South America. In just two words, buen vivir includes concepts of degrowth, dematerialism, alternative development, happiness, and collectivism. Similar to some of the other loanwords, buen vivir has its roots in indigenous society.

Buen vivir is loosely translated from sumak kawsay, or the cosmovision (world view) of the Quechua. This world view sees humans and nature existing in communion based on harmonious totality of existence (the necessary interrelation of beings, knowledges, rationalities, etc.). The term has inspired social movements advocating for an alternative paradigm of development that is balanced, culturally-appropriate, and communitarian. The defining principle of the collective in buen vivir paves a path separate from that of capitalism and the mechanisms created to put a price on nature, such as ecosystem services. Under the outlook of buen vivir, humans cannot own the earth – we can only act as stewards.

The ideas coming into fruition today from the belief systems of indigenous cultures like the Quechua are visible in concepts like the sharing economy or collaborative consumption.

———

Our words are our ultimately our tools to construct a vision of the future. We must stretch ourselves beyond the limits of the Anglosphere to incorporate multiculturalism and multilingualism in understanding how we talk about our relationship with the earth and our connection to future generations. With the publication of Loanwords to Live With, we can begin to speak in the way we wish to act, living in harmony.