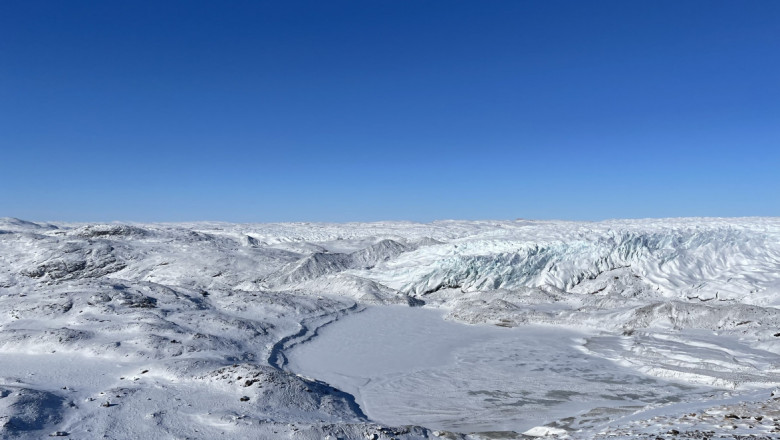

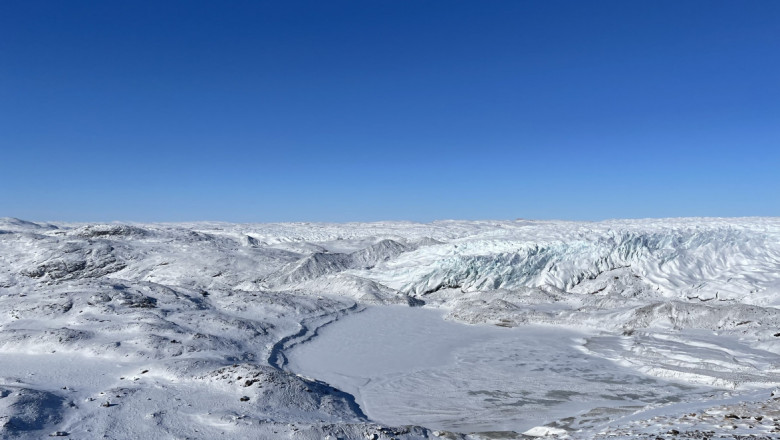

Greenland's ice sheet is slowly melting. Several sought-after resources are becoming increasingly available as a result. (Mia Rosenblatt)

Greenland's ice sheet is slowly melting. Several sought-after resources are becoming increasingly available as a result. (Mia Rosenblatt)

When I spent a week in Greenland last spring, it was impossible for me to miss how residents’ lives have been affected by the climate crisis. Now Greenlanders face a new dilemma, or perhaps a new opportunity.

Since 2002, the Greenland Ice Sheet, a vast body of ice that covers 80% of the island, has been losing 273 billion metric tons of ice per year. This immense number signals that the ice sheet is in a negative mass balance, meaning that the ice is melting faster than it can be replenished. According to Inger Seierstad, an ice core scientist who lives in Denmark and took part in Greenland ice core drillings, there have been periods of unusual warmth in Greenland in recent years and melting events so major that they have occurred at the top of the ice sheet – which is historically extremely rare.

It is no secret that this ice melt is due to the effects of climate change, which are causing the oceans and air temperatures to become significantly warmer, especially in the Arctic regions. As a result, Greenland is seeing immense changes, from thinning ice and glacial front retreat to new areas opening up for resource extraction.

With Greenland’s ice melting away, the extraction of several different kinds of resources has become an increasingly important topic of recent debate. According to multiple sources, three of the main resources in contention are metals (such as nickel and cobalt), glacial flour (a mix of sediments deposited by the glacier), and trade routes.

Mining for nickel and cobalt has only become a possibility in recent years due to the fact that the ice melt is exposing more land, making it easier to mine. Metals like nickel and cobalt are used in the production of certain technologies, such as batteries, and thus are essential for electric cars and renewable energy sources. Thus, many have argued that mining in Greenland could actually help mitigate the climate crisis by allowing us to produce more sustainable energy opportunities. Billionaires have flocked to Greenland in a “treasure hunt” for these metals with the promise that this will end up being beneficial for the planet.

However, it is also important to note the consequences of mining for metals such as these. These mines not only cause significant pollution, but also damage the previously pristine landscape. One study on a few of Greenland’s former mines shows that these areas are still polluted with metals decades later. The study strongly advocates for Environmental Impact Assessments (the process that evaluates likely environmental impacts of a project), especially in areas such as the Arctic where the ecosystems are so delicate.

Glacial flour, or the sediment that is directly deposited by the glacier itself, is also a valuable resource that many are hoping to extract given its growing availability as a result of increasing glacial melt. The sand that the glacier pumps out is actually the perfect consistency for making concrete. The sediment also has the potential to be added onto farms as a kind of fertilizer. According to the IPCC, climate change is also affecting our food systems thus, using this glacial flour to create nutrient-rich soil could be extremely beneficial for our future. Even though this idea is still in the early stages, scientists have stated that the extraction process wouldn’t be as invasive as mining for metals because glacial flour often accumulates on the banks of glacial lakes and rivers, where digging is not necessary to extract it.

As the Greenland ice sheet melts, the trade routes around the area become more navigable for longer periods of time. A variety of different routes will open up, allowing for ships to more efficiently take Northern routes instead of the traditional Southern ones. Researchers at Brown University have pointed out some of the positives of an increased diversity of trade routes, noting that a lot of these Arctic trade routes can be shorter than typical ones like through the Suez Canal. These shorter routes would save fuel, thereby reducing carbon emissions and contributing less to our already increasing climate change problem. However, the Arctic is extremely remote, and there are minimal emergency response systems in place. Therefore, accidents in the Arctic have an even greater impact on an already delicate area. If a shipping accident or oil spill were to occur along these new routes, it would be incredibly difficult for Greenland and other Arctic stakeholders to respond quickly.

When examining Arctic issues, it is essential to also address the Indigenous population in the area. Greenland has a complex and difficult history, and it is ultimately still part of the Kingdom of Denmark. Thus, in any of these decisions surrounding mining, sand extraction, or trade routes, it is important to consider the Greenlandic perspective. It is worth mentioning that the population of Greenland is 88% Inuit. The dilemma that Greenlanders have to weigh is the conflicting goals of preserving the intrinsic beauty of their land and the pristine nature of the island versus increasing their financial independence from Denmark.

A recent survey, however, showed that 75% of Greenlanders would support the extraction of the sand deposited by the glaciers. Crucially, the majority of those surveyed prefer that this extraction is done so that Greenlandic people are able to receive the profits, thus leading to greater financial independence from Denmark.

Even though Greenland’s melting ice is clearly dire, many are seeing an opportunity to leverage this situation to promote initiatives that could ironically mitigate our global climate impact. However, ice core scientist Seierstad takes a broader perspective. She notes that these proposed initiatives like mining, sand extraction, and re-routing of trade routes are “not solutions to the climate crisis.” Rather, she puts the emphasis on the big picture: “We need to find a way to reduce our carbon emissions drastically by moving away from fossil fuels, and we will need to carbon capture as well.”

While caught up in the growing excitement around resource extraction, we can’t lose sight of the larger picture that Greenland’s melting ice is an anthropogenic tragedy, or one that has been caused by humans. Seierstad also said that, “climate change is happening extremely fast in the Arctic – so fast in fact that Greenlanders can see it almost from year to year.” Seierstad is also witnessing how glaciers are shrinking and how sea ice is thinning or disappearing since her first visit to Greenland in 2001.

This ice melt is affecting the livelihoods of many, if not all, of those that live in the Arctic. Should we choose to extract, we should bring all stakeholders to the table and run environmental impact assessments to know exactly how any new initiative would affect the area. And for Greenland’s sake in particular, let’s not take our focus away from the broader, global solutions that will make the largest impact.