Illustrations by Sachi Kitajima Mulkey.

Illustrations by Sachi Kitajima Mulkey.

In California, native plants are back in vogue. On its website, the California Native Plant Society lists over 200 native plant nurseries in the state. The Los Angeles Times maintains social media accounts just for stories about native plants.

After a century of hard-fought controversy over invasive varieties such as toxic and flammable eucalyptus trees, shoreline-enveloping ice plants, and the unstoppable pampas grass dominating everything else, it seems residents of America’s most biodiverse state have had enough. But for Indigenous cultures, this latest trend in gardening is old news.

Native societies have lived in California for thousands of years, gathering and propagating native plants for food, medicine, crafting material, and cultural practices. As the environmentally destructive side of western agricultural practices becomes increasingly impossible to ignore, even state legislators have turned to traditional ecological knowledge for best sustainability practices in environmental planning.

“Native peoples are able to now tell their own stories,” says Nicholas Hummingbird, whose popular classes on Indigenous knowledge are offered through his native plant-focused Instagram. “Not be seen as victims of a genocidal past, but show what we have always been capable of.”

In lecture halls, in the greenhouse, and on Zoom, the students of Hummingbird and other Indigenous teachers not only learn how to care for native plants, but how to build a reciprocal relationship with nature.

Before the curtain fully closes on the California summer, heatwaves turn the valley of Santa Ynez into a frying pan, toasting the landscape and residents with temperatures over 105 degrees Fahrenheit. Several times a week, Diego Cordero turns his back on the Santa Barbara ocean breeze and makes an hour-long commute to the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians reservation to check on the native plant nursery where he works.

“I can’t miss a day of watering with brutal heat like that,” says Cordero, “I’ll lose a bunch of plants.” Cordero is the lead environmental technician for SYCEO, the Santa Ynez Chumash Environmental Office, where he works with a small team to monitor, manage, adapt, and restore the natural ecosystem on the reservation.

While many native plant nurseries exist across California, Cordero says the nursery on the Santa Ynez reservation is “a little bit different.” Instead of focusing on plants with ornamental value, aka pretty enough to put in your lawn, he often works in collaboration with the tribe’s cultural office, focusing on plants that the tribe would historically use in every-day life. Plants are provided to members of the tribe on a suggested donation basis.

“Even if the plants aren’t endangered, they’re hard for people to get to,” says Cordero, who says that many of the most sought-after native plants are native to wetland habitats, which are often now the sites of California’s major cities. According to the California Water Quality Monitoring Council, 90% of California’s wetlands are now lost. Other popular plants are grown in grassland habitats, where according to the 2016 textbook, “Ecosystems of California,” 90% of the native plants have been replaced by non-native or invasive varieties.

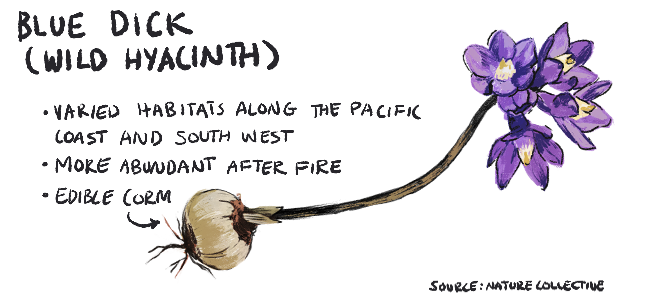

As climate change continues to alter the natural landscape on the reservation, members of the tribe can look to the nursery on the Santa Ynez reservation for a healthy, well-managed stock of their most culturally significant plants. Medicinal plants, such as the cold-remedying yerba mansa, are available for those with experience using medicinal plants. Juncus, also known as black rush, can be dried and woven by basketweavers. Blue dick, which Cordero describes as a slow-to-propagate, but “pretty little plant,” grows a garlic-like bulb, known as a corm, which is delicious when roasted and served as a historically significant source of starch.

To keep the wealth of knowledge of native plants flowing to the next generation, the Santa Ynez Chumash Environmental Office runs several educational programs throughout the year. For the Homework Club, a youth education program in collaboration with the Tribal Learning Center, Cordero and other team members teach kids about the native plants and ecosystem on the reservation through scavenger hunts, art projects, and hands-on workshops. The Environmental Office coordinates with the culture department for activities at Camp Kalawashaq, a children’s environmental summer program, and hosts Chumash earth day celebrations, and reservation clean-up events.

Cordero sees the resiliency of the tribe mirrored in his favorite class of plants, native grasses. He says the secret to these plants’ survival is in the depth of their roots, which can go up to 12 feet deep to seek out any traces of moisture in the soil, allowing them to survive long periods of drought.

“It’s literally a deep-rooted existence,” Cordero says. Despite hardships, “eventually the rains do come.”

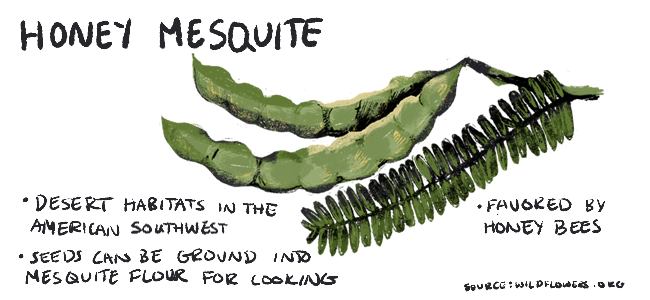

The fruit of the prickly pear ripens in spring, peppering the desert landscape of Southern California with its magenta flesh. In the summer, the plump green pods of the honey mesquite tree are ready for picking. In the fall, rich, starchy California black oak acorns tumble from their canopy.

Gerald Clarke Jr., a member of the Cahuilla Band of Mission Indians and two-time elected tribal official, has fond memories of gathering edible plants throughout the year with his two daughters and making traditional dishes. “It’s really a plant calendar,” he says, explaining that the Cahuilla tribe would follow the annual growing cycles of edible plants across the diverse landscape of Southern California, gathering plants intentionally to ensure a plentiful supply year after year.

But as a professor of Ethnic Studies at UC Riverside, Clarke says he follows the plant calendar in addition to an academic one. This balancing act is one he has long practiced: Before teaching Indigenous culture and history, he shared his sculptural and conceptual art practice with college students as head of the art department at Northeast Texas Community College and assistant professor at East Central University.

Clarke’s art focuses on Indigenous themes, blending multimedia methods of weaving, sculpture, and painting. But due to the scarcity of native plants in natural environments, Clarke says he doesn’t employ traditionally-used native plants in his art. “If I’m going to go out and gather plants, I want it to be for something vital to my subsistence, you know?” he says. “I don’t want to use the forest to make art. I don’t like to cross those boundaries.”

Into his classes at UC Riverside and art studio alike, he carries the weight of Indigenous history. “Native plants and native history are inherently interlinked. The organized genocide of the environment and our people are one and the same,” says Clarke. His students not only learn a comprehensive curriculum on TEK, a popular shorthand for traditional knowledge, but the importance of applying this knowledge correctly. Clarke and other scholars say well-intentioned policies often ignore the diversity of California’s ecosystems: What works in one environment could harm another.

“Fire is a great example I always share with my students,” Clarke says. Studies have shown that before colonial settlement in the 1800s, Indigenous tribes regularly practiced cultural burning as a method of forest management, contributing to an estimated 4.5 million acres of California that would naturally burn each year. But after colonization, a zero-tolerance fire suppression policy took over, leaving the forest underbrush to become the kindling fueling the deadly megafires of recent decades.

Only since the spring of 2022 has state legislation begun to clear the way for prescribed burns to manage this crisis, but historical cultural burning practices are not necessarily the same thing. Indigenous activists say that seasonal timing, methodology, and post-fire management derived from TEK are more effective at restoring biodiversity and ecological health.

Clarke’s students are angry, and he loves it. “They’re like, ‘why didn’t we know that?’ There’s a hunger for the truth, not the romanticized history we’ve been taught since kindergarten,” he says. In the classroom, he strives to uplift his students to action.

“If I just focused on the things that we’ve lost, I think that’s a depression we’d never recover from. Instead, I focus on the miracle that we’re even still here,” he says.

In a Zoom class in early December, a PowerPoint slide shows a young boy gently smiling at the just-gathered acorns cupped in his palms. His father and instructor of the class, Nicholas Hummingbird, named him Tuhui, which means a drop of rain in the Samala language, historically spoken by Indigenous tribes in Southern California.

“It only takes a drop of rain to germinate a seed, for a seed to seek out more water,” Hummingbird says. “But the promise of that seed is a new beginning, a new future.”

In his popular online classes on native plants, Hummingbird’s students can pay on an affordable sliding scale to take two-hour online classes on a broad range of topics, spanning from the minutiae of tending to native plants in your own backyard, to Indigenous uses for California native plants. Through his Instagram @California_Native_Plants and @_Native_Hummingbird, Hummingbird sells and ships seeds to students who live in the state and occasionally offers in-person cooking classes with the native plants that he gathers with his son.

“My job as an educator is to take what I’ve learned, and make it accessible to anybody and everybody so that we are on equal footing,” says Hummingbird, whose lessons are not only drawn from his lived experience as an Indigenous person but also his background in native plant management in both national park service and private native plant nurseries. While building Hahamongna Native Plant Nursery in Pasadena, California, Hummingbird grew his reputation as a teacher and horticulturist, leading a team of volunteers to sustainably and responsibly propagate native plants with habitat restoration in mind.

Even with these successes, Hummingbird found these experiences bittersweet, opening his eyes to the widespread mismanagement of native plants. In his classes, Hummingbird pulls no punches: His students not only learn how to grow seeds, but how to spot ignorance and manipulation. “Money is the incentive, not a better environment,” he says. “People with good intentions can cause catastrophes when they’re not given context or the right information.”

To offer his students a deeper understanding of his culturally-driven techniques for responsible plant propagation, Hummingbird’s lessons weave the complex relationship between the historical genocide of Indigenous people, habitat loss, and climate change. “When you have a concept of the past, you know what has been lost,” he says, referencing the widespread biodiversity loss in California due to single-crop agricultural practices, or landscaping with invasive plants that decimate native plant populations. “Do we double down on the arrogance of settler colonialism and try to make failed practices work?”

While there is some knowledge he won’t share out of respect for his community, he hopes his work informing the greater non-native public can contribute to a “better, more livable” future.

“At the end of the day, I’ll take what I’ve learned, and give it to the next generation,” says Hummingbird. He compares teaching to walking down a path together, with no experts and only mutual learning. “Even if my footsteps only go so far, yours can then continue on that journey.”