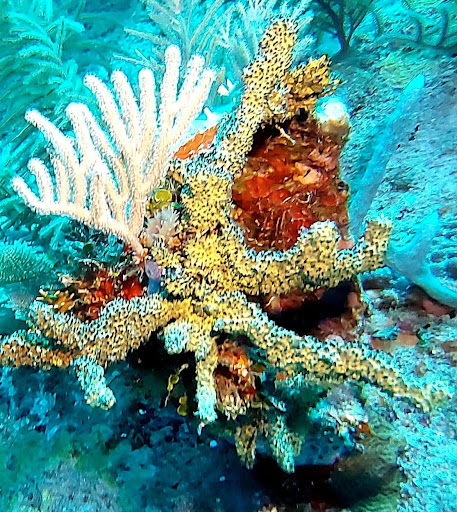

Staghorn coral outplants at Cane Bay, St. Croix. (Kemit-Amon Lewis)

Staghorn coral outplants at Cane Bay, St. Croix. (Kemit-Amon Lewis)

It was back in 2015 when I was scuba diving in Cane Bay on the west end of the island of St. Croix. I was lying in the water, floating on my back, when an entire school of baby squid swam right next to me. As I moved, the babies all turned at once in response to my movement. Then, as I dove down under the surface, I saw the magnificent coral reefs, bright and brilliant. I swam around the reef and I saw two sea turtles eating sea grass and later ascending to the surface for air. Just as I was getting ready to surface as well, I saw what looked like little poles with coral on them. I swam over to look. I had no idea what they were, but knew I needed to learn more.

I asked my best friend, who lives on the island of St. Croix if she knew about what was in the water in Cane Bay. “Those are coral reef nurseries,” she said. My friend suggested that I speak with Kemit-Amon Lewis, one of the marine scientists working on the coral reef nurseries in St. Croix. These are places where marine scientists rehabilitate salvaged corals to later be transplanted back into wild colonies.

I talked with Lewis about coral reefs and the coral bleaching that is taking place due to rising water temperatures, and he had some very valuable information about coral reef bleaching events. In these events, increased water temperature stresses out corals and causes them to turn white and appear bleached. When corals go through a bleaching event, they are at a great risk of death unless water temperatures go down.

Lewis is the Development Director at the Perry Institute for Marine Science. His role within the Perry Institute is to explore strategic partnerships and, otherwise, support ocean conservation work in the Bahamas and some other Caribbean islands. Lewis has been working on reefs since 2010 and is involved in many programs to help the coral reefs including, BleachWatch Citizen Science Program, the “Reef Responsible” sustainable seafood campaign, and PADI Coral Nursery and Restoration Specialty Diver Course.

After a near-death experience in 2019 from an unknown bacterium, resulting in septic shock, and suffering multiple amputations, Lewis has brought special attention to reef recovery programs and has lectured about his journey after losing his limbs. He is a personal inspiration to me, as he is still a scuba diver and photographer of the ocean.

Lewis talked about his memories of the Virgin Islands’ beautiful waters and reefs and how the local public-school marine biology program introduced him to marine science as a child. He also has many fond memories of his family’s time spent on the west shore where he learned how to snorkel. He said that the first time that he saw a coral bleaching event was in the Virgin Islands in 2010. There were large areas of bleaching, but temperatures did not persist for a longer period.

“Some of the corals paled instead of bleached,” he said. “A lot of corals appeared able to rebound from that bleaching event and not be completely lost. This is excellent news that the corals rebounded after a bleaching event, which proves that coral can rebound and become healthy again.”

Coral reefs have been going through coral degradation for 40 years, caused by anthropogenic activities that have warmed the ocean due to increased greenhouse gasses. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has been monitoring bleaching events using satellites for over 20 years and has collected extensive data showing that a coral reef can recover many times after bleaching takes place.

Some of what has helped coral reefs recover are marine sanctuaries. These are protected waters that include habitats such as coral reefs and are important in sheltering the coral reefs from such things as over-fishing and damage by collisions with passing boats. Regarding the use of marine sanctuaries to conserve the coral reefs and sea life, Lewis said, “They can be very successful if properly managed, to protect the coral reefs.” He continued, “They help to ensure there is no overfishing and [contribute to the] protection of reefs.”

Coral bleaching is not a phenomenon unique to the Virgin Islands. It is happening across the equatorial world. I have a friend, Melissa Drapeau, who lives in Honduras, whom I have known for many years. Like me, she was also a SUNY-ESF student studying biology and has been an avid diver for 30 years. She said she has observed coral bleaching gradually grow worse over the last couple of decades.

“[It went] from a single coral that was bleached out, and one that was obviously ill for some reason, to it being patches of coral and then being more widespread areas and then now seeing a lot of that,” Drapeau said. “Whether it is bands on the coral where half the coral appears alive, and half of it is bleached out.”

Honduras has a program called the Coral Reef Alliance, which has made great strides in protecting the coral reefs, focusing on clean water, healthy fisheries, and habitat protection. This program along with several other factors have helped Honduras to have some of the healthiest coral reefs in the Caribbean.

There are several things that we can do to help protect the beauty of the ocean and the coral reefs, which include using reef-safe sunscreen, not using single-use plastics, recycling and properly disposing of trash. Additionally, Lewis had some solid advice for scuba divers and anyone exploring the ocean, “[Be] mindful of not touching stuff… I know it’s our nature as human beings to be inquisitive and to pick up random stuff, however, just observe them,” Lewis said. “Our eyes are there for a reason. Take pictures and leave bubbles.”