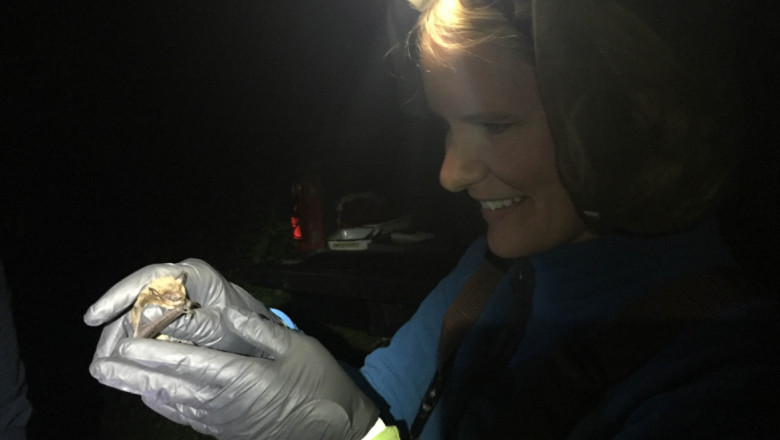

Hohoff uses outreach opportunities to dispel misconceptions about bats. “Just showing people a picture of me holding a bat in my hand, they get an idea of scale,” she said. (Image courtesy of Tara Hohoff)

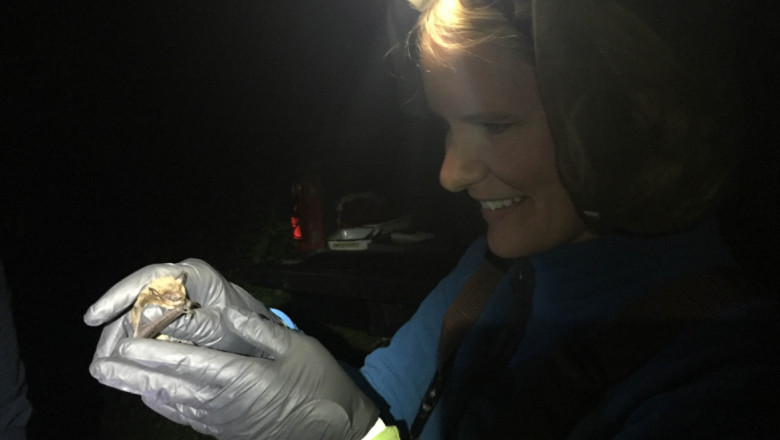

Hohoff uses outreach opportunities to dispel misconceptions about bats. “Just showing people a picture of me holding a bat in my hand, they get an idea of scale,” she said. (Image courtesy of Tara Hohoff)

By Sarah Anderson

In 2013, Joe Kath entered a mine and immediately spotted a bat with a white nose. This fuzzy, silvery mustache announced that white-nose syndrome, a deadly bat fungus thought to have spread from Europe to North America by travelers, had inevitably invaded Illinois. “It was kind of like a gut punch, but we also knew it was coming,” said Kath, the endangered and threatened species manager at the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

When COVID-19 emerged seven years later, conservation researcher Tara Hohoff was instructed to stop handling bats. This pause in her work wasn’t implemented because the bats might give her the virus, but rather because she could transmit it to the bats. “I think there’s this fear of: What if we now introduce something else to these bats?” said Hohoff, an associate mammologist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and co-leader of the Illinois Bat Conservation Program.

Six out of Illinois’ 13 bat species are classified as endangered, subjected to a myriad of threats ranging from disease to clean energy to agricultural development. Researchers across the state are working to protect bats, studying species abundance, activity and habitat to guide conservation practices. Facing the aftermath of association between bats and COVID-19 and a period of increased rabies cases from bat bites, conservationists are engaging in public outreach to gain support for an often criticized, yet critical, creature. “These organisms that we are so hard on are incredibly valuable to our persistence as a species on this planet,” said Mark Davis, a conservation biologist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and co-leader of the Illinois Bat Conservation Program.

With mortality rates exceeding 90%, white-nose syndrome has killed about 7 million bats in North America since it was detected on the continent in 2006, Kath said. The affected species include the federally endangered Indiana bat and the northern long-eared bat as well as the “common” tricolored bat and little brown bat. White-nose syndrome has depleted over 90% of the northern long-eared, tricolored and little brown bat populations, according to the United States Geological Survey. Given this devastating toll, the latter two species may soon be listed as endangered or threatened, Kath said.

Clean energy-producing wind turbines deliver the second of a “one-two punch” against Illinois’ bats, Kath said. The red bat and the hoary bat forage at about the same altitude as the turbine blades, leading to mass mortalities. Destruction of bat habitats for agricultural production is another major hurdle for local bats, Davis said. “All of these factors have conspired together to make life as a bat in Illinois really difficult in the past 20 years,” he said.

The decline in bats presents a significant problem for Illinois’ corn- and soybean-based economy. One study estimates that by eating insects that damage crops, bats save the agricultural industry approximately $23 billion in pesticide each year. “More pesticide application results in higher food costs to the average consumer, and then the ball just keeps rolling,” Kath said.

The cascades will continue to reverberate. A dwindling bat population could lead to a boom in their disease-spreading mosquito prey and threaten the pollination and seed dispersal services they provide in other regions. “It sounds like hyperbole, but it’s not,” Davis said. “The loss of bats from our ecosystems would be catastrophic.”

Illinois’ bat researchers are doing their part to keep catastrophe at bay. Hohoff’s work focuses on recording bats’ unique echolocation calls to identify different species and map their distribution patterns. She uses ultra-fine “mist nets” to capture, examine and release bats to corroborate the species indicated by the acoustic signature.

Kath also uses mist netting to survey bat activity during the summer. Some bats are fixed with a radio transmitter, which sends out a signal that can be tracked to find the trees where they roost. He then performs emergence counts, tallying how many bats leave the roost in the evening to help measure local population levels and pinpoint critical habitats. In the winter, he monitors bats at hibernation sites like caves and abandoned mines.

Davis’ research involves analyzing the DNA in a bat’s excrement, called guano, to determine its species and study its diet, which helps him understand how bats are using the landscape.

Collectively, this information can help prevent destructive land management and development projects, such as constructing a wind farm in an area with heavy bat activity or cutting down trees in areas with endangered species.

While Illinois’ bats haven’t turned the corner yet, the researchers have seen glimmers of hope. Death rates due to white-nose syndrome seem to be slowing, Davis said. Europe’s bats eventually developed immunity to the disease, and Davis is trying to find out if the same process is happening in North America now. To do so, he is analyzing bats’ genetic material before and after the arrival of white-nose syndrome to look for any mutations that might grant resistance to the disease.

Habitat conservation projects have also brought good news. Hohoff and Davis partnered with the prairie conservation organization Grand Prairie Friends to evaluate bat activity in habitats converted from agricultural fields and found that bats quickly returned to enjoy the restored land. Kath collaborated with the mining company Covia to stabilize the Magazine Mine at the southern tip of Illinois, which has since become the second largest hibernation site for Indiana bats in North America.

Working to save animals battling extinction is typically regarded with respect and admiration, but bat conservationists face the unusual challenge of unfavorable public perception of their advocate organism. “Bats are a fairly maligned critter, and oftentimes, people have negative connotations associated with them,” Davis said.

In addition to media coverage linking bats to COVID-19, bats have been at the center of a recent cluster of rabies cases. Bats lead the risk of death from rabies in the United States, according to the CDC. Every animal that tested positive for rabies in Illinois in 2021 was a bat, but only 40 were identified in the entire state, according to the Illinois Department of Public Health. “Not an awful lot of animals test positive, but enough to cause an impact on public health because rabies is a deadly disease,” said Mabel Frías, the assistant director of the Communicable Disease Control Unit at the Cook County Department of Public Health.

In the fall of 2021, three people in the United States—one in Illinois—died after contracting rabies from a bat. Two of the exposures were considered “avoidable,” and all three failed to receive the post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) injection that can prevent rabies before the onset of symptoms, according to a press release from the CDC. The release highlights the importance of avoiding contact with bats and receiving PEP after a potential exposure. Public health responses should focus on preventing disease transmission rather than eradicating bats, Frías said. “The value of bats to our economy far outweighs the risk they present to human health,” Davis said.

Still, in light of this bad press, Illinois’ bat researchers have worked hard to garner investment in bat conservation. At the start of the pandemic, Hohoff seized every speaking opportunity she could to remind people that the source of COVID-19 hasn’t been confirmed and that it’s humans’ responsibility to erect barriers with wildlife. Kath has collaborated with the Illinois Department of Public Health to develop seminars on how to minimize the risk of bat encounters. “We do a lot of work with the public to try to relay the message that we need to coexist with bats because our livelihoods depend on them,” Davis said.

In some ways, their efforts have already paid off. Requests to place acoustic recorders on private property are largely successful, and some citizens are actively participating in bat conservation, identifying bat roosts and performing their own emergence counts. Hohoff has noticed that her presentations tend to attract a younger audience that is excited about bats. “I do think things are changing,” she said.

The team hopes their research, conservation and outreach work will help protect an underappreciated part of the environment. “I’m inspired to try to make some sort of a difference to ensure that these things that have captivated me throughout my life and that provide tremendous value to us as a species are around for future generations,” Davis said.