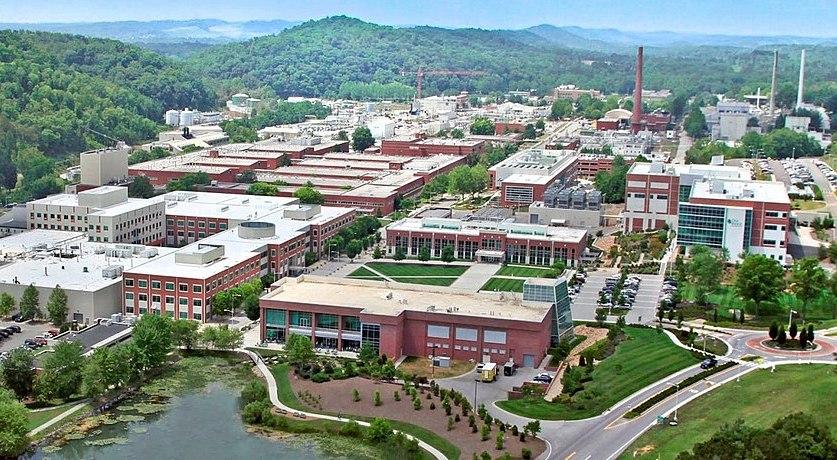

An aerial view of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. (U.S. Department of Energy)

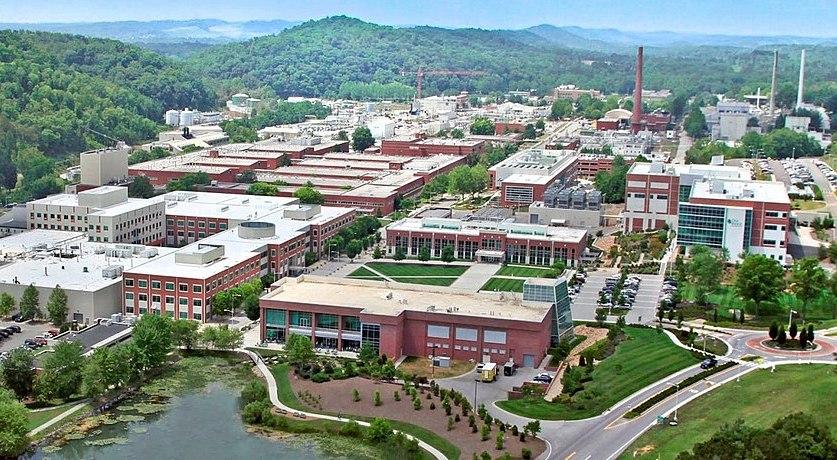

An aerial view of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. (U.S. Department of Energy)

In the Appalachian foothills of East Tennessee lies the country’s largest federally-run science and energy facility: Oak Ridge National Laboratory. ORNL, as it’s known to locals, was established in 1943 as one of the Allied forces’ heavily guarded, secret nuclear research facilities under the Manhattan Project. Though the lab continues to lead the country in innovations in nuclear science and technology, its campus now accommodates a staff of 1,100 scientists and engineers across 100 different disciplines, all devoted to the research and development of energy sciences and technologies, according to an ORNL fact sheet.

Within the chemical sciences department at ORNL, postdoc Neil Williams describes his work as creative problem-solving. When asked in an interview why he took a position at ORNL as a researcher, he replied, “I really like to solve problems. Many scientists and engineers are this way. We can’t stand not having an answer to something.” His current energy problem to solve? Climate change.

By the late 19th century, scientists had begun to argue that human emissions of greenhouse gases could, in theory, change our relatively stable climate. By the 1960’s, carbon dioxide, or CO2, had been identified as a prime contributor to the warming greenhouse effect. Due to sustained global fossil fuel use, atmospheric CO2 has increased 45% since the greenhouse effect was first theorized 150 years ago, as reported by NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory. In response, scientists and CEO’s have recently shifted their focus from prevention to mitigation in the form of CO2-capture technologies.

Williams, under principal investigator Radu Custelcean, recently stumbled upon a unique form of this CO2-capture technology, which he thinks will offer the market an energy-efficient, cost-effective alternative to technologies already on the market. Using commonplace items like a household humidifier and a solar hotdog cooker, Williams and his team were able to create a small-scale direct air capture (DAC) mechanism which can capture, store, and release CO2 from both CO2-saturated industrial flue gas and air in the environment with relatively minimal energy consumption.

Typical DAC processes involve passing air over a solid or liquid CO2-sorbing agent. The (usually alkaline or basic) CO2-sorbing agent will bind with molecules of CO2, effectively lowering the concentration of CO2 in the air. Before the CO2-sorbing agents can be used again, they must be heated to release the CO2 they’ve bound with. The released CO2 can then be stored for commercial applications or permanently sequestered from the atmosphere. The process is cyclical and energy-intensive and commonly used to scrub CO2 from industrial flue gas streams with high concentrations of CO2.

Custelcean and Williams offer two potential major improvements on this traditional method of scrubbing CO2 from both CO2-laden flue gas streams as well as environmental air. Their method introduces new, potentially less-corrosive sorption media in the form of aqueous amino-acid solutions and a new sequestration and release medium in the form of an organic salt called 2,6-pyridine-bis(iminoguanidine), or BIG for short. There have been relatively few new methods of DAC introduced into literature in recent years, and existing methods require temperatures up to 800 degrees Celsius (about as hot as a glowing lava flow), whereas Williams and his team achieved CO2 release between 80 and 120 degrees Celsius (the temperature range of your average sauna).

On the team’s goal, Williams said, “What we’re aiming to do is create a technology that can perform just as well as what’s on the market…that can remove CO2 very effectively and rapidly, then store that CO2 from the solution by scrubbing that solution with compounds we developed called BIGs. Where our technology is a great improvement on what’s already been developed is that we dropped the energy associated with recycling or regenerating the sorbents by introducing these BIGs.” Employing a household humidifier to wick CO2 from the air and a solar hot dog oven to then release that CO2 using the thermal energy provided by the sun’s rays, the team was able to produce consistent, scalable results that offer a completely new mechanism to the field of CO2 scrubbing. Their plan is to finesse the solutions using their benchtop pilot model before eventually experimenting at large-scale, industrial sites.

Quoting a paper from the National Academy of Sciences, Williams asserted that CO2 sequestration will be vitally important for mitigating the effects of climate change in the future, claiming that even if we stopped emitting CO2 from all sources, the amount of CO2 already in the atmosphere would continue to drive up global temperatures on inertia alone. “So it’s important to not only focus on zero-emission standards but also to find a low-energy way to remove CO2 directly from the atmosphere,” Williams argued. “Also, there are companies out there that need CO2 for commercial purposes, and they’re saying, ‘If I can just pull it directly from air, I don’t need to pay people for it. I can just go do that myself.’ So streamlining this technology incentivizes companies to employ it in their factories and production facilities.”

There’s a quote attributed to Isaac Asimov on a magnet stuck to the filing cabinet in Williams’ office: “The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not, ‘Eureka! I’ve found it,’ but, ‘That’s funny!’” Down the hall, a colleague has a comic taped up outside his office door that says, “Research is what happens when you have no idea what you’re doing.” Global warming is a new foe in humanity’s fight for survival on planet Earth, and CO2 is the central culprit. If we are to stand a chance against the ill effects of rising greenhouse gas concentrations, our species will not be saved by a glamorous figure who makes a grand gesture that saves us all in one fell swoop. Instead, our survival depends on scientists like Williams, in labs like ORNL, with household humidifiers and hotdog cookers in hand, taking a second look at data and saying, “That’s funny…”