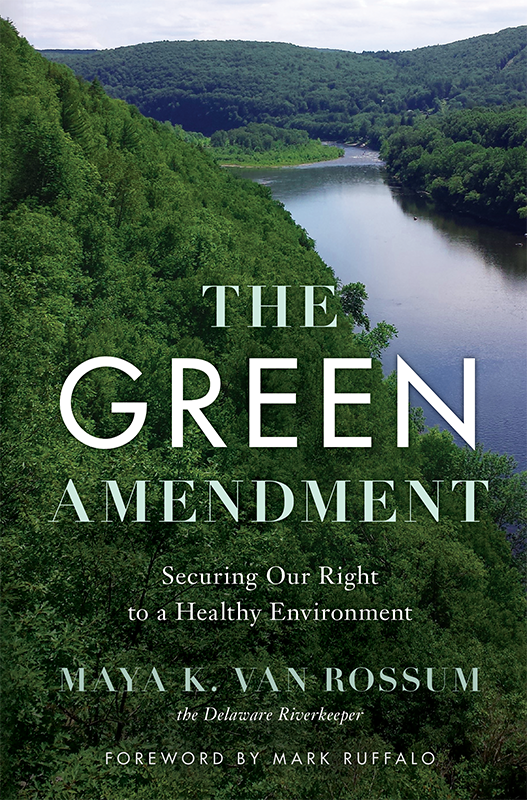

Maya van Rossum, shown here at an event in 2014, recently released a new book called “Green Amendment: Securing Our Right to a Healthy Environment.” (Chesapeake Climate/Creative Commons)

Maya van Rossum, shown here at an event in 2014, recently released a new book called “Green Amendment: Securing Our Right to a Healthy Environment.” (Chesapeake Climate/Creative Commons)

Maya van Rossum has been the leader of the Delaware Riverkeeper Network since 1994. She has been an active environmentalist throughout her career, focusing on protecting the Delaware River watershed in its entirety. She recently released a new book called “Green Amendment: Securing Our Right to a Healthy Environment.” In her book, van Rossum advocates for a constitutional approach in the fight for a clean environment. Planet Forward sat down with the author and advocate to discuss some of the subjects she touched upon in “Green Amendment.”

Planet Forward: Can you tell us a little bit about your work at the Delaware Riverkeeper Network and how you got involved in this group?

Maya van Rossum: My official title is the Delaware Riverkeeper. My job is to be the voice of the Delaware River. What that means is that I work hard to make sure that any time decisions are being made, or actions are being taken that would impact the Delaware River or any of its contributory streams, that the Delaware River has a voice in the room. [I make sure] its needs and goals of protecting it are given the highest priority in the decisions that are being made. Now of course that’s not the job of one person. There’s no one person that can protect an entire river or, certainly, an entire river’s watershed. It really requires a community effort. And so, I do have a wonderful community that works with me. I have a staff of 20 at the Delaware Riverkeeper Network… and then we have nearly 20,000 members throughout the watershed that help us fight the good fight for the river.

Planet Forward: In your book, you talked a lot about the failures of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. Can you tell us why these environmental agencies tend to fail at fulfilling their basic duties? Would you equate these failings to regulatory capture [that is, where a regulatory agency doesn’t act in the public interest]?

van Rossum: So it’s not just in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, it’s really every environmental agency at the state level and at the federal level across the nation. They are not doing anything and everything that needs to be done to protect our natural resources, [and] in order to protect people’s health safety and the quality of their lives. A fundamental reason why that’s the case is because the laws in the United States of America, whether we’re talking local, state, or federal law, are not written to prevent environmental degradation or to protect people’s rights to a healthy environment. [These laws] are actually written to allow pollution. They just put in place a process to identify: how much, when, and where that pollution or environmental degradation will be allowed. The implications for community health, individual health, and individual and community quality of life isn’t given independent consideration in that legal process. It’s presumed that people’s right to a healthy environment or the concept of the right to a healthy environment will be protected by virtue of the fact that you’re going to regulate the how, when, and where environmental degradation takes place. It’s not really considered, legally, on its own as an overall concept that needs to be achieved. In some cases, such as the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, regulatory capture is absolutely taking place. That is a federal agency responsible for reviewing and approving pipelines and fracking infrastructure projects. In over 30 years, FERC has only denied one pipeline project brought before its commissioners for approval. There are a handful of ways we can demonstrate that that agency really does suffer from regulatory capture. And I’m sure there are others depending on the state you’re talking about. However, broadly speaking you don’t have to have regulatory capture for agencies to day in and day out be making decisions that really side with industries ability to pollute, over the health and safety of people.

PF: You also talk about the overbearing power that industries and corporations have when it comes to forming policy in the United States. Do you think the U.S. has reached a point in our democracy where it is dominated by oligarchical forces, especially after Citizens United v. FEC?

van Rossum: I think we’ve reached a very problematic situation in the United States, were people’s rights, people’s needs, people’s voices really are subservient to the desires, goals, and greedy nature of industry. Many politicians prioritize their own political careers and desires to advance and make money, over their obligation to protect the health and safety of people and the environmental resources we depend upon. I think that the U.S., for a long time, has been suffering from this reality that people are subservient to the goals and desires of industry, who [are able to] capture politicians. I do think that it is getting worse and worse every year. Part of it is because of legal decisions such as Citizens United that make it easier for industry to co-op with politicians and hold the power of the purse over their heads — if they want to continue their political careers. That being said, I think we’re at a tipping point, a moment in which the overreach by industry and self-serving politicians, is now blatantly obvious to an increasing number of people. No longer are people counting on their representatives to do the right thing and prioritize people’s needs over industry’s needs. People are now trying to find ways to hold government officials accountable. So while rallies, protests, and certainly voting are important ways to do that, I think that the passage of constitutional provisions to protect our environmental rights is a high priority way to hold government accountable for protecting people’s right to a health environment.

PF: Can you tell us more about this constitutional approach to environmentalism and why that would be more constructive than our current legislative approach?

van Rossum: So our constitutions, whether you’re talking about the state constitution or federal constitution, are above the law. So when you have a constitutional right, like the right of free speech, it’s a higher level of protection. Government officials have to prove they are complying with the law but also have to prove they are complying with the constitution. In the case of the environment, if you have a situation where an industrial operator is spewing pollution into a waterway, and the people downstream are upset about it, these citizens may not be able to do anything because the operator has a permit to pollute backed by standing law. But if there’s a constitutional provision in place, the industrial operator and the government official stating that they complied with the law on the books is not good enough. [A constitutional right] is another layer of review and another obligation for protection. If a constitutional right to a healthy environment is violated, or a person believes their right has been violated, they can go to the courts to vindicate their right. They do not need a law written by a legislature… they can go straight to the courts.

PF: If a concerned citizen does notice environmental degradation occurring in their community, how should they go about defending their right to a clean and healthy environment?

van Rossum: If you’re seeing pollution, you’re going to want to contact your local regulators. This might be your local town or the police if it’s a significant danger. All state agencies and federal agencies have pollution hotlines you can contact to request for a survey of damage that may be taking place. You may even have a constitutional issue if you live in Pennsylvania or Montana which do have constitutional protections for the environment. If your state doesn’t have a constitutional protection, then you’re really going to have to count on your regulatory agencies or state law. And if these avenues fail, that might just inspire a person to fight for a constitutional right for a clean environment within their state.