In the heart of Austin, Texas, lies a salamander sanctuary that exists as a backup, in case the wild population were to be wiped out — but is it enough to save the species?

The salamanders at the end of the world

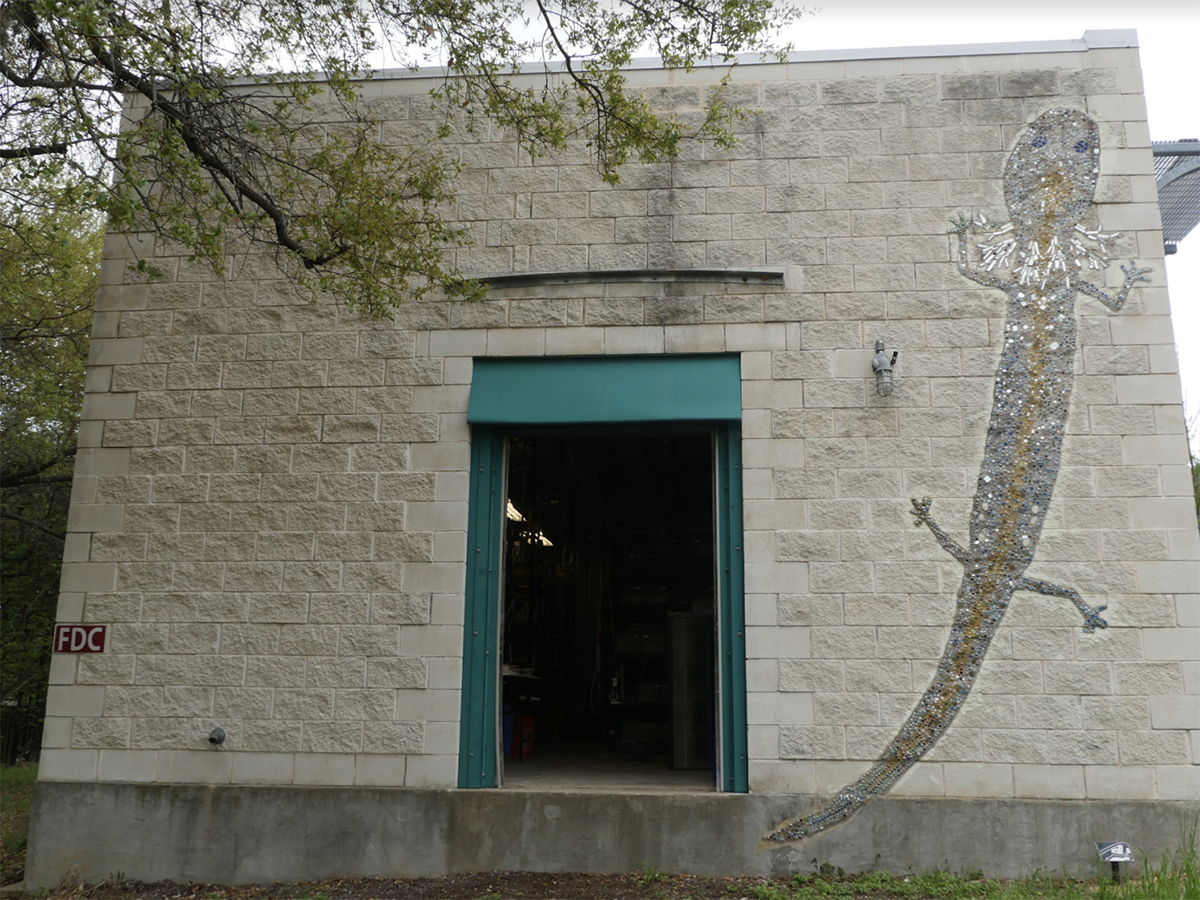

At the heart of the Austin Science & Nature Center, a mosaic of a salamander scales the exterior of an otherwise nondescript cinder-block building. The salamander’s body is a deep, royal blue, with a gold stripe cut through the center. Chunks of reflective glass scatter light, making the salamander look like the inside of a kaleidoscope, or perhaps, like a deity. The salamander’s tail almost brushes the grass at the building’s base, and its snout reaches just shy of the roof. It’s looking up, perhaps even crawling up, as if it wants to know what’s on the other side.

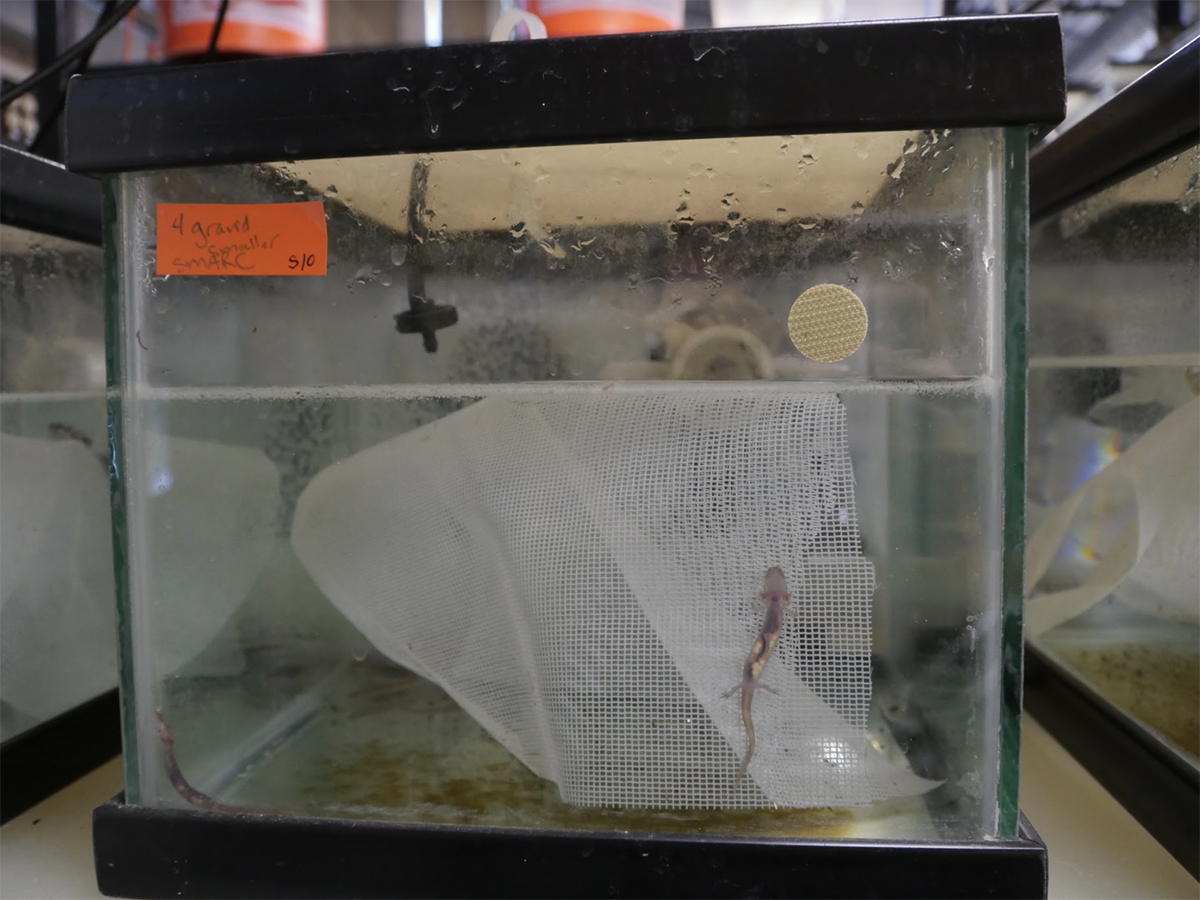

Inside the building, in tanks stacked ceiling-high, the mosaic’s real-life counterpart peers through glass, hiding behind plastic sea grass. Aside from the size difference (these salamanders are just three inches long as adults), the striking patterns of the mosaic aren’t far off. Their translucent skin is spotted sometimes with yellow and opal; other times with orange, or purple, or magenta. In the right light, their tiny hearts beat through luminous skin. Pink gills protrude from their necks like an old-fashioned ruff. Looking at their gills through a microscope, one can see red blood cells absorbing dissolved oxygen. Close observation is crucial, each scientist knows, for when the tank water’s chemical balance is just slightly off — too much or too little calcium or dissolved carbon dioxide or heat — the salamander may expand, balloon-like, or develop other strange health problems. In response, an irrigation system sends well-fresh spring water to each tank, drip by drip.

“I find them very fascinating animals,” said Dee Ann Chamberlain, an environmental scientist with the City of Austin and the steward of this captive population. “They’re small. They’re beautiful when you see them up close.”

Years ago, Chamberlain spent 12 hours watching a female salamander lay her eggs, which are stored in her abdomen. That day, the salamander lay each egg with great care, choosing each location separately before placing her eggs in the safety of the plastic plants, netting, and filter media. Once laid, the eggs take three to four weeks to mature. Looking closely, one can see the white orb morph into a white squiggle, then into something that resembled the tiniest salamander — just half a centimeter in length at hatching. When I visited the captive breeding facility, I saw salamanders so slim they could have been a splinter, and so short they could easily be squashed.

This pampered population exists as a backup, ready to sire offspring that would be released if the wild population were to die off — a wild population that exists just a few hundred meters but also a world away from the captive species — where water emanates, myth-like, from deep within the earth. But, some say, even if that population were to be released, it may not be enough to save the species.

***

The Barton Springs Salamander is endemic to the cool, isothermal waters of Barton Springs Pool — a three-acre, one-eighth-mile swimming-hole and terminus of the vast Edwards Aquifer of Central Texas — one of the largest artesian aquifers in the world. Barton Springs natural haven for Austinites — home to ancient religious rituals, ardent scientific inquiry, and polar plunges alike — and is lauded as the city’s ‘crowned jewel.’ The Barton Springs Salamander was discovered in the late 1980’s by David Hillis, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin. Soon after describing the species, Hillis’ team discovered that the species was most likely critically endangered from the effects of development, poor water quality, and the aggressive cleaning methods used on Barton Springs Pool. If added to the endangered species list, the Barton Springs Salamander would receive special protections from the government to help species recovery.

The Barton Spring Salamander was filed for the official endangered species listing in 1990. Seven years later, after many legal battles, political faux pas, and scientific surveys, the salamander joined the endangered species list. Developers and politicians feared the endangered species listing of a creature whose habitat happened to be in the heart of Austin would stifle development. Austin did craft a stricter watershed protection ordinance, but instead of hindering economic growth, Austin became an even bigger boomtown. In Austin’s southwest suburbs, construction rumbles over the aquifer’s fragile recharge zone. And the wild population of salamanders, sensitive to the slightest change in their habitat, continues to stare extinction in the face.

In 1998 — one year after the Barton Springs Salamander (or Eurycea sosorum) got its endangered species listing — the captive breeding program began. The captive facility of Barton Springs Salamanders (and the endangered Austin Blind Salamander) exists as a backup population, in an effort by the City of Austin to conserve the species. “In case there’s an issue with wild populations, you can put them back — Noah’s Ark,” said Andy Glusenkamp, the Director of Conservation and research at San Antonio Zoo and a member of the Barton Springs Salamander Scientific Advisory Committee. The population’s technical name is a “captive assurance colony,” which means that it must represent 85% to 95% of the wild genetics. This effort requires meticulous tracking of which salamander breeds, and when. Dante Fenolio, Vice President of the Center of Conservation and Research at San Antonio Zoo said it took him ten years just to figure out how to breed one species on command. “The answers to these things,” Fenolio said, “They’re not intuitive. And they’re not easy.”

One of the reasons the questions are so hard to answer is that there’s a significant knowledge gap when it comes to salamanders. “Salamanders overall are not well studied,” said Chamberlain. “We’ve had to learn a lot in order to maintain them.” And after decades of close observation, Chamberlain remains in awe of these creatures. “Salamanders have amazing abilities,” Chamberlain added. “They can regenerate more organs than any other vertebrate on the planet.” Talking to Chamberlain, it seems that the body of unanswered questions about salamanders are as boundless as the Edwards aquifer itself.

But perhaps the most salient question is, what would happen if the wild population disappeared? “Despite decades of preparation,” wrote a journalist for Austin Monthly in 2018, “There’s just too many variables.” Herpetologists have devised countless doomsday scenarios — each worse than the next. The oil pipelines that stretch across the area’s recharge zone could crack. A pathogen could infect the water table. A sewage line could bust. A drought could de-water the aquifer. The City of Austin does have development regulations, but that doesn’t stop construction in the suburbs. Local protections can’t halt the threats of climate change leading to bigger droughts, and the omnipresent threat of a chemical spill that could wipe out the species faster than biologists could save them. “To date,” Glustenkamp said, “There’s no way to remove any of those threats once they appear.”

Even if the aquifer were to become restored, the question remains, in the words of Fenolio: “How do you put a salamander back into an aquifer?” Fenolio knows of no successful reintroductions of salamanders to a groundwater system — nor of any attempts to reintroduce the species. Chamberlain believes that it might take years of releasing salamanders and monitoring the population’s response before reintroduction is successful. Glusenkamp is not so optimistic. “It’s very difficult to put a three-inch salamander back in the springs without it washing out,” he said. “Do I think that we’re gonna be able to T-shirt cannon salamanders back to their habitat and we’re gonna restore species after extinction events? No.”

If the wild salamanders were to be wiped out, the captive salamanders would not be alone on the metaphorical ark. They would join the ranks of other species with the distinct Red Class listing of “Extinct in the Wild,” or EW — from the sky-blue Spix’s macaw to the regal South China Tiger to the acid-yellow Panamanian Golden Frog — species that don’t exist in the wild anymore, but instead live a captive half-life. This is the “very core of one of the key and critical problems with conservation biology,” Fenolio said. “What do you call it when you have a species in captivity… their habitat is gone in the wild, (and) you can’t put them back anywhere? Is it conservation anymore, or is it curation?”

This beckons the question: should we reintroduce the species, if it goes extinct? If the aquifer remains polluted, should humans step in and try to salvage it? Fenolio suggested that one may be able to inject medical-grade de-activated carbon into the water which tends to bond and sequester contaminants, but that may not be effective, and may do more harm than good. In that case, does one play God and find a new home for the species, risking the introduction of a new pathogen, or of another Australian Cane toad catastrophe? Do we leave the salamanders in captivity for perhaps hundreds of years until a “a “biblical flood,” as Glusenkamp puts it, refills the aquifer with clean water? This brings to mind John McPhee’s remark in his book, “The Control of Nature” (and echoed by Elizabeth Kolbert in “Under a White Sky”) on how the rerouting of the Mississippi in the Eisenhower era “will come to mind more or less in echo of any struggle against natural forces — heroic or venal, rash or well-advised — when human beings conscript themselves to fight against the earth.” Would injecting de-activated carbon, and t-shirt-cannoning captive raised species into this fragile environment be a trespass over our role as humans, “to surround the base of Mount Olympus demanding and expecting the surrender of gods?” Or is it our unique duty to do just that?

“I think everybody involved in this would agree, (reintroduction) is the last tool you want to use,” Glustenkamp said. “Absolutely the last tool. And it’s incumbent on all of us to do everything we can to avoid using that tool, by taking other actions.” Thankfully, there are many who continue to steward the aquifer and its inhabitants. Documentary filmmakers educate the public about the beauty and fragility of Barton Springs. The lawyers at the Save Our Springs Alliance hold local governments and developers accountable to clean water regulations. And the scientists at the city of Austin who work to monitor wild populations and restore degraded habitat — those who grapple necessary truth that one day the wild salamanders may be gone — who cradle their black-spotted heads and watch oxygen diffuse through their gills — may be the species’ fiercest advocates. “Last time I checked, two-inch long blind salamanders made of jelly aren’t very good boxers,” Glustenkamp said. But Austin’s scientists have their gloves on, ready to go to the mat on this one.