Strange Lake Huron sinkholes may be the key to finding life on other planets

Special microbial mat systems in Alpena, Michigan, are helping scientists search for extraterrestrial life.

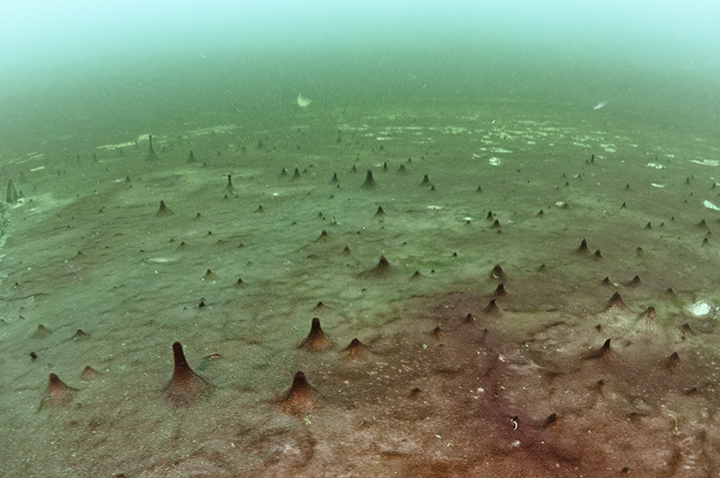

“It’s so different, and feels otherworldly,” said Stephanie Gandulla, a diver with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Thunder Bay Marine Sanctuary. She has sampled the mats near the sinkholes on the lake’s bottom.

You may have seen a microbial mat before — the green algae on wet rocks at the beach is an example.

Algae’s green color comes from chlorophyll — a substance that uses sunlight to turn carbon dioxide into energy. Carbon dioxide and oxygen support most of life on Earth.

But under special conditions, like those at three sinkholes just two and a half miles east of Alpena, primitive forms of microbes called cyanobacteria can survive without either of them.

These are white, not green, and they get energy from chemicals in the water.

“They are everywhere, but they are incredibly hard to find,” said Bopaiah Biddanda, a biologist with Grand Valley State University’s Annis Water Resources Institute, who has been studying them for 20 years.

Such mats are normally found in ocean waters over 32,000 feet deep, but they can be found only 80 feet below the surface of what is known as Lake Huron’s Middle Island Sinkhole.

The sinkhole’s biologically extreme environment can help simulate sample collection in extraterrestrial worlds where life is based on similar chemicals. A new study by Biddanda models scenarios where robots could analyze material beneath the water of other planets. It’s based on the work in Lake Huron.

The study focuses on two methods: suction devices for soft mats and coring devices for hard mats.

The sinkholes near Alpena provide sulfuric, oxygenless groundwater that creates the conditions needed for the mats to grow. Filaments of cyanobacteria drift together, creating a wispy white-purple flow.

“It almost looks like a mirage,” Gandulla said.

It could be a long time before the experience from sinkholes in Lake Huron will be used to explore the potential of life on planets elsewhere, but Biddanda’s exploration is yielding other finds now.

Recently, for example, his team found an explanation for the mats’ mysterious ability to change colors overnight.

The purple and white cyanobacteria travel upwards to capture energy from the top of the mat, according to the study. During the day, microbes with color capture the small amount of sunlight reaching the seafloor with chlorophyll.

As the sun sets, the white microbes move to the surface of the mat to absorb chemicals in the sulfuric water for their energy. This continuous, vertical shift in microbes causes patches of the mat to change between purple and white in a daily cycle.

The microbial mats thrive off a special soup of chemicals in the groundwater, but changes in land use could disrupt it in the future.

The Thunder Bay sanctuary is constantly combating such threats to coastal ecosystems such as the one near Alpena.

“Development might choke off the water supply,” Biddanda said.

The marine sanctuary offers educational programs and tours to K-12 students and operates a welcome center year-round.

“We work together to protect it as a community,” Gandulla said.

The characteristics of Middle Island Sinkhole’s cyanobacteria could hold the key to much more than planetary exploration. They could lead to advances in other scientific fields, such as evolutionary biology and medicine.

“We have a library of pharmaceutical value here,” Biddanda said. “This could help us down the road.”

And, he noted that they look cool: “There is something fascinating and mesmerizing about these colorful mats.”