Courtesy of Karen Harland

Courtesy of Karen Harland

Steelwork smoke in the air, young faces on their way to school, and the familiar silhouette of industry in the distance. This is Teesside — a region tucked away in the northeastern corner of the British Isles, long burdened by a legacy of petrochemical production and laborious toil.

In the early 2000’s, Tees Valley thrived as the steel-making capital of the world, shipping raw materials to even the most remote edges of the globe. However, in 2015, the collapse of the region’s iron and steel industry saw a shadow cast over the manufacturing heartland, tarnishing the pride and grit of the “Smoggies,” a community now marked by economic deprivation and environmental pressure.

Today, Teesside has become one of several dumping grounds for the nation’s waste, hosting multiple incineration and landfill sites. And with the construction of a new waste-incineration facility looming in the future, local families, councillors, and grassroots campaign groups are expressing concerns over regional air quality and economic hardship.

The Tees Valley Energy Recovery Facility (TVERF) is a waste-incineration site proposed for the area of Grangetown, a historically deprived district of the UK where average healthy life expectancy falls well below the national average. This large-scale, £2.4 billion (approximately $3.2 billion) infrastructure project is a publicly led initiative, organized by a partnership of seven different councils across the North East. With the promise of 50 permanent jobs, and enough electricity to power 60,000 homes, the facility frames itself as a sustainable alternative to landfill for managing residual waste — material that cannot be recycled.

However, alarm bells have begun ringing over these sustainability claims and some community members allege that the operator of the site, Viridor, has not had a promising environmental track record. A 2025 UK governmental report by the Environment Agency outlines 916 breaches of pollution limits at a station in Southern England, which the company attributed to human error in calibrating monitoring software.

Tristan Learoyd, an unaffiliated independent councillor from Teesside said that the proposed site holds “massive effects for the environment locally and for the planet internationally.”

“It’s a cumulative effect of one incinerator after the other,” Learoyd said. “The TVERF will produce more carbon than the whole of Redcar and Cleveland,” he said, referencing one of the councils involved in the proposal. This issue, he adds, makes a “mockery of anyone” who installs a heat pump, lowers their carbon footprint, or drives an electric vehicle.

However, according to a statement provided on behalf of the project partners, the TVERF will be “future-proofed,” designed not only to generate electricity but also to export heat and capture carbon emissions if the opportunity to develop supporting infrastructure arises.

Meanwhile, Learoyd highlights that projects of similar waste-composition globally have shown levels of pollution that could cause severe damage to lung health, lead to heart problems, and accelerate brain issues such as dementia. These concerns are particularly significant at a time when air pollution already claims the lives of more than 30,000 individuals in the UK per year.

“The TVERF is regressive. It’s not needed,” said Fiona Dyer, a volunteer and campaigner for the North East Climate Justice Coalition, and Stop Incineration North East. “People are thinking about their kids, and their kids’ futures.”

As of 2023, the North East region’s capacity for processing residual waste is on target to exceed municipal needs based on volume of solid and residual waste. And, with the introduction of government recycling schemes such as the Circular Economy Package, the amount of waste available for incineration in districts like Teesside becomes increasingly scarce.

According to advocates like Dyer, there is a broad suspicion that, as fuel supplies drop, more waste will be shipped in from elsewhere as councils potentially buy up refuse to avoid penalties for missing incineration targets.

Learoyd expands on this, arguing that councils importing waste, alongside paying gate fees for incineration, covering carbon taxes on emissions, and funding the initial contract with operator Viridor, will result in a “15% increase in council tax for every single payer in the North East of England for 30 years.” This concept, he adds, is an “economic disaster and politicians need to wake up.”

In contrast, the TVERF project partners maintain that this technology is the only “safe, reliable, sustainable, and affordable” solution for disposing of the region’s residual waste. They further claim the facility will create “hundreds of employment and training opportunities,” while injecting “nearly £30 million [$40 million] over the contract term” into the local economy and its communities.

Critics argue that despite assurances, these financial complications could not only negatively affect individuals in Teesside already facing cycles of entrenched poverty, but also threaten environmental targets.

“What I anticipate councils will do is they’ll deliberately reduce the amount of recycling they do, so they’ve got more to burn in the incinerator,” Learoyd said.

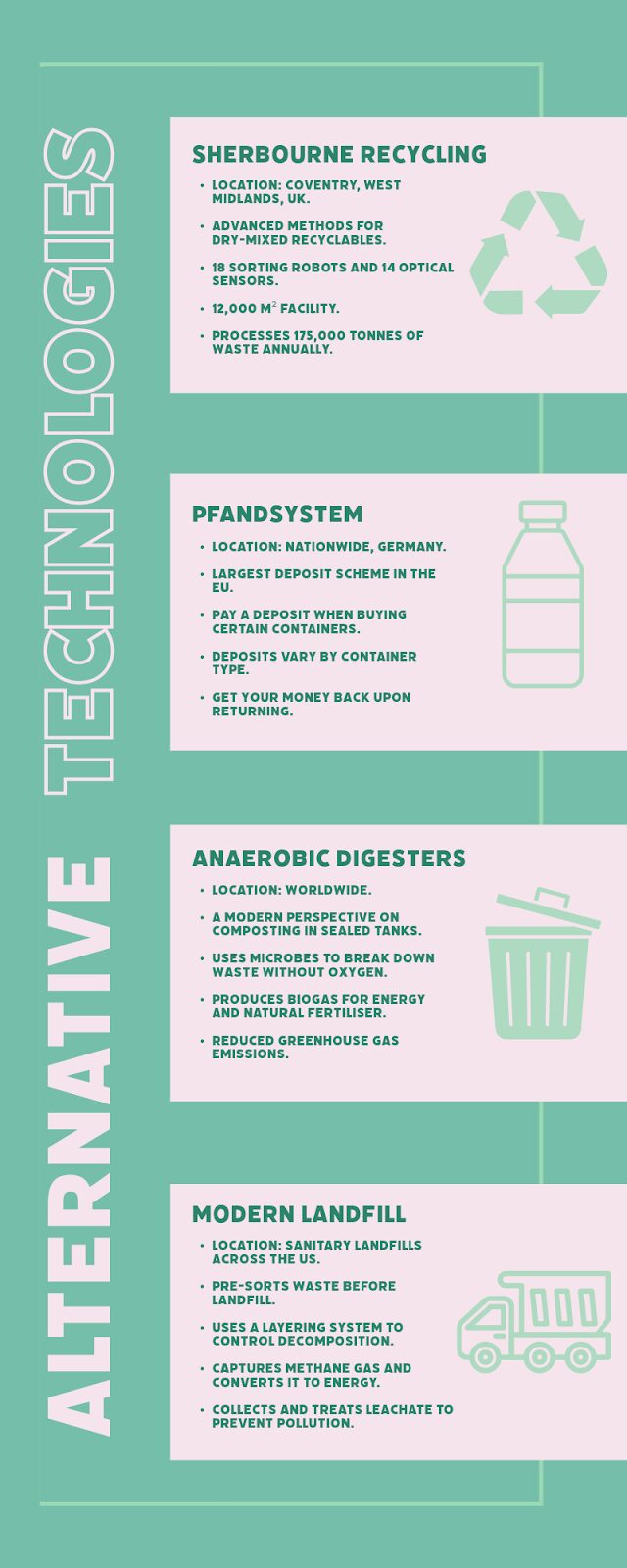

Nonprofit organizations such as the North East Climate Justice Coalition have urged regional councils to accelerate investment into highly innovative forms of waste management that present a promising alternative to incineration for Teesside.

Particular focus has been placed on a facility within the English midlands, known as Sherbourne recycling. This publicly organized program, managed by eight local authorities, uses industry-leading AI sorting and machine technology to process residential curbside waste more efficiently.

Serving a population of 1.5 million people, roughly the same population the proposed TVERF aims to cover, this model shows potential for adoption in Teesside. Nevertheless, observers argue that for an initiative like this to succeed, an amendment of local government direction and re-allocation of funds may be necessary.

Grassroots charitable group, Stop Incineration North East (SINE), are a collective who have advanced suggestions for alternatives to the TVERF. From compiling in-depth reports on anaerobic digesters for food waste management to debating modern U.S. landfill practices — aimed at reducing methane emissions through secured containment — SINE’s grassroots level work is focused on spreading awareness for these alternatives.

Dyer, a spokesperson for SINE says, “We are very keen to get people, more young people in the area to actually join the campaign or support it.”

With the TVERF set to begin construction in 2026, and operations anticipated to commence in late 2029, a verdict on the facility’s sustainability remains unclear. A transparent review of the project and potential alternative technologies could therefore help address community concerns and steer Teesside toward a cleaner, more sustainable future.