(Christina Trexler/University of Arkansas)

(Christina Trexler/University of Arkansas)

Author’s note: This essay is inspired by Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species,” Chapter III. I analyze the checks and advantages of a potential invasive species in the Galapagos Islands following the format of Darwin’s third chapter, “Struggle for Existence.”

***

Plasticus Vastum affects the lives of each and every one of us every day, and it is spreading across the Earth at rates unmatched by nearly any other species to date, so why haven’t we heard about it?

The short answer is that the research on this species is new, and many are hesitant to report on the dangers of its growth, because its existence inarguably improves the quality of life of most humans today.

Traces of Plasticus Vastum can be found in homes, automobiles, food, computers, clothing, any many other locations. It’s established a huge presence, yet we too often refuse to acknowledge it for what it is. Plasticus Vastum is a species belonging to the Omnes Materiales family, referred to by some as Plastika Apovlita.

The species was first discovered in 1907 by Leo Hendrik Baekeland, a Belgian born American scientist. However, it is believed that this species has dated back to the pre Columbian civilizations in Mesoamerica as far back as 1600 BCE. Plasticus Vastum is a particularly diverse species, as its lifespan can range from 10 years to over 1,000 years depending on different characteristics.

It has also shown promise in adapting to different climates and is one of the few species that can survive at soil and sea. Members of the species can take many different shapes and sizes, which is where they derive their name, Plasticus, which means capable of shaping and molding. The species’ unique reproductive tendencies can be described through a mutualistic relationship with humans and erratic spawning.

To expand, all species belonging to the Omnes Materiales family have a mutualistic reproductive method with humans where, when one or many members of the species serve as a direct facilitator of human life, like bees become vehicles for the reproductions of flowers, humans become vehicles for the reproduction of species belonging to Omnes Materials.

For Plasticus Vastum in particular, humans have enabled the growth of over 6.3 billion tons of growth in only the past 70 years. Furthermore, each member of Plasticus Vastum can produce thousands of offspring without the need for human intervention through erratic spawning. (Note: The appearance of Plasticus Vastum is measured by weight rather than individuals in a population solely because it is extremely difficult to count the individuals since they are constantly spawning and regrowing into various shapes and sizes.)

Jessica Howard, a research assistant in marine bio-invasives at the Charles Darwin research station, has been able to share her firsthand account of the appearance of the species in the Galapagos Islands.

She said it has “come in and caused problems for the endemic and native wildlife or the economy,” which is by definition an invasive species. Their unique reproductive tendencies, where any single being can produce thousands of offspring, but the offspring can’t grow without a mutualistic relationship with humans, highlight the extreme danger of this invasive species to spread rapidly, but also give hope that humans could learn to adjust their ways to prevent the growth of offspring.

We may need to act fast, however, because the wildlife of the Galapagos Islands are already facing a struggle for existence to accommodate the large amounts of Plasticus Vastum.

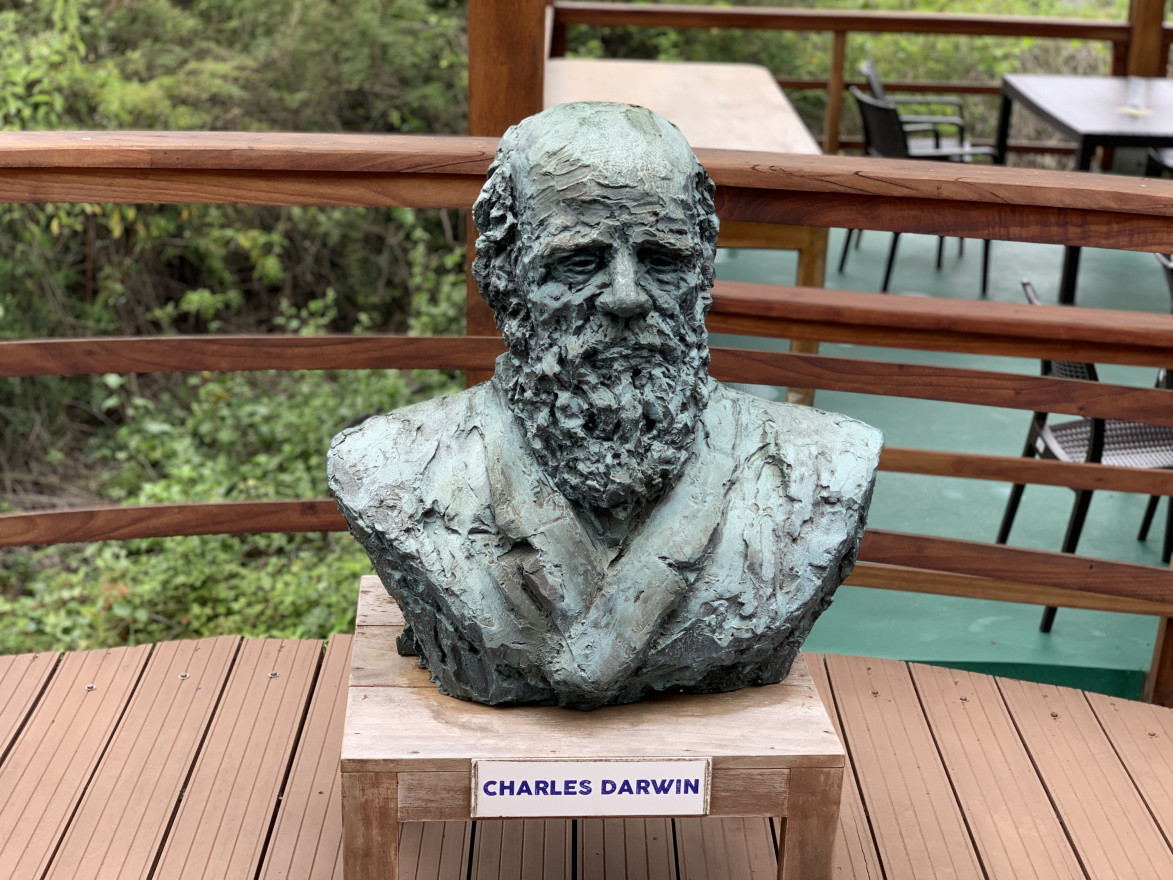

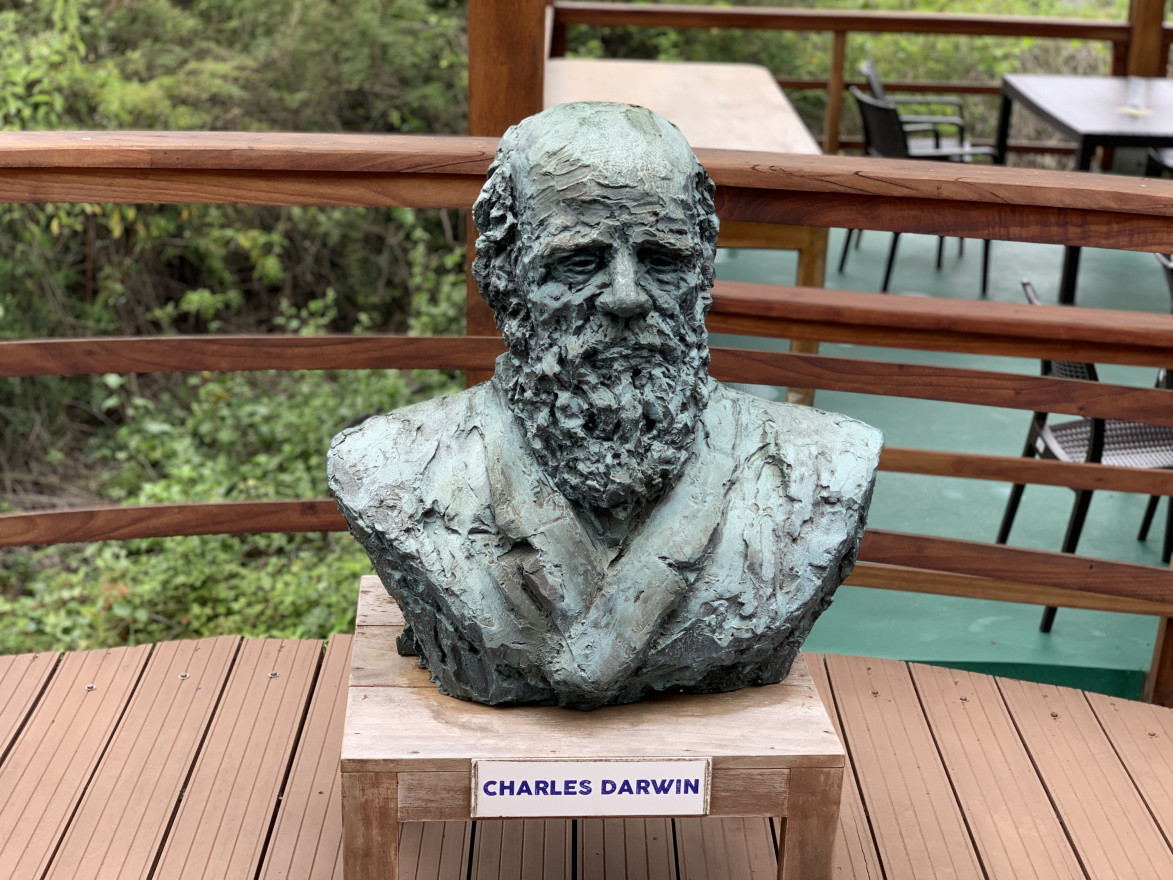

Before entering the subject of this chapter I must make a few preliminary remarks to inform the reader of the connection between Charles Darwin, the struggle for existence and its bearing on natural selection, and Plasticus Vastum in the Galapagos Islands.

“On the Origin of Species,” published on Nov. 24, 1859, is a work of scientific literature by Charles Darwin which is considered to be the foundation of evolutionary biology. The third chapter of this book is titled “Struggle for Existence” and it serves as an introduction to Darwin’s main argument for natural selection. Charles Darwin’s theory was heavily influenced by his travels to the Galapagos Islands. In fact, our first association with the word “Galapagos” very well may be Darwin, or perhaps Darwin’s finches.

In this chapter, Darwin uses botany, zoology, and mathematics to get to the heart of his argument on natural selection, and today, we are going to revise his argument with our modern knowledge of Plasticus Vastum. While Plasticus Vastum has been showing up across the globe, the focus in this essay will be its appearance in the Galapagos Islands in honor of Charles Darwin’s studies there. For the remainder of this essay, we will refer to Plasticus Vastum as PV for brevity. Direct quotes from Darwin will be in italics, whereas my own analysis will be in regular print.

“I should premise that I use this term in a large and metaphorical sense, including not only the life of the individual, but success in leaving progeny. Two canine animals in a time of dearth, may be truly said to struggle with each other which shall get food and live. But a plant on the edge of a desert is said to struggle for life against the drought, though more properly it should be said to be dependent on the moisture. A plant which annually produces a thousand seeds, of which on an average only one comes to maturity, may be more truly said to struggle with the plants of the same and other kinds which already clothe the ground. The missletoe is dependent on the apple and a few other trees, but can only in a far-fetched sense be said to struggle with these trees, for if too many of these parasites grow on the same tree, it will languish and die. But several seedling missletoes, growing close together on the same branch, may more truly be said to struggle with each other. As the missletoe is disseminated by birds, its existence depends on birds; and it may metaphorically be said to struggle with other fruit-bearing plants, in order to tempt birds to devour and thus disseminate its seeds rather than those of other plants. In these several senses, which pass into each other, I use for convenience sake the general term of struggle for existence.”

It is important to note here that the particular struggles that PV face are not completely understood, but there does seem to be a correlation between human carriers of PV and its profound growth in recent years. Due to its mutualistic relationship with humans, it could be hypothesized that it struggles with other species of the Omnes Materiales family whom could fill its mutualistic niche with humans.

Similar to the missletoe’s struggle with other fruit-bearing plants, in tempting birds to disseminate its seeds rather than those of other plants, PV struggles to tempt humans to facilitate it’s growth and disseminate its progeny rather than those of other species belonging to Omnes Materiales.

An important discussion, however, is not how PV struggles with other species, but how many species are struggling because of PV. PV, with its many shapes and sizes, can be mistaken for food by many lifeforms, but scientists agree that it does not provide enough nutritional content to sustain any of these animals, which can lead to their eventual death.

More intelligent lifeforms may not mistake PV for their typical food, but they are susceptible to contamination by consuming prey that have ingested PV. PV has been found in the stomachs of sea turtles, sea lions, birds, iguanas, tortoises, and fish, and it is currently one of the greatest threats to these Galápaganian species.

That is why there have been tremendous efforts in the islands to reduce the presence of PV, many of which have been successful. However, a single nations efforts to reduce an invasive species which has the means to travel via land and sea with lifespans upwards of 1,000 years is insufficient, as evidenced by the findings of PV originating from Peru and other countries showing up in the Galapagos Islands.

So with the unsuccessful efforts of PV eradication, how should we anticipate the struggle for existence of the many beautiful and unique lifeforms in the Galapagos Islands to be challenged by PV?

“A struggle for existence inevitably follows from the high rate at which all organic beings tend to increase. Every being, which during its natural lifetime produces several eggs or seeds, must suffer destruction during some part of it’s life, and during some season or occasional year, otherwise, on the principle of geometrical increase, its numbers would quickly become so inordinately great that no country could support the product.”

By this principle, more individuals are produced than can possibly ever survive, so in every case, including PV, there must be a struggle for existence, either one individual with another of the same species, or with individuals of a distinct species, or with the physical conditions of life.

It is likely unlikely for PV to struggle within itself, and it has been shown to survive in many extreme climates and conditions, so the question of eradicating plastic as an invasive species seems to fall into the category of struggle for existence with individuals of a distinct species, which can fulfill the same niche.