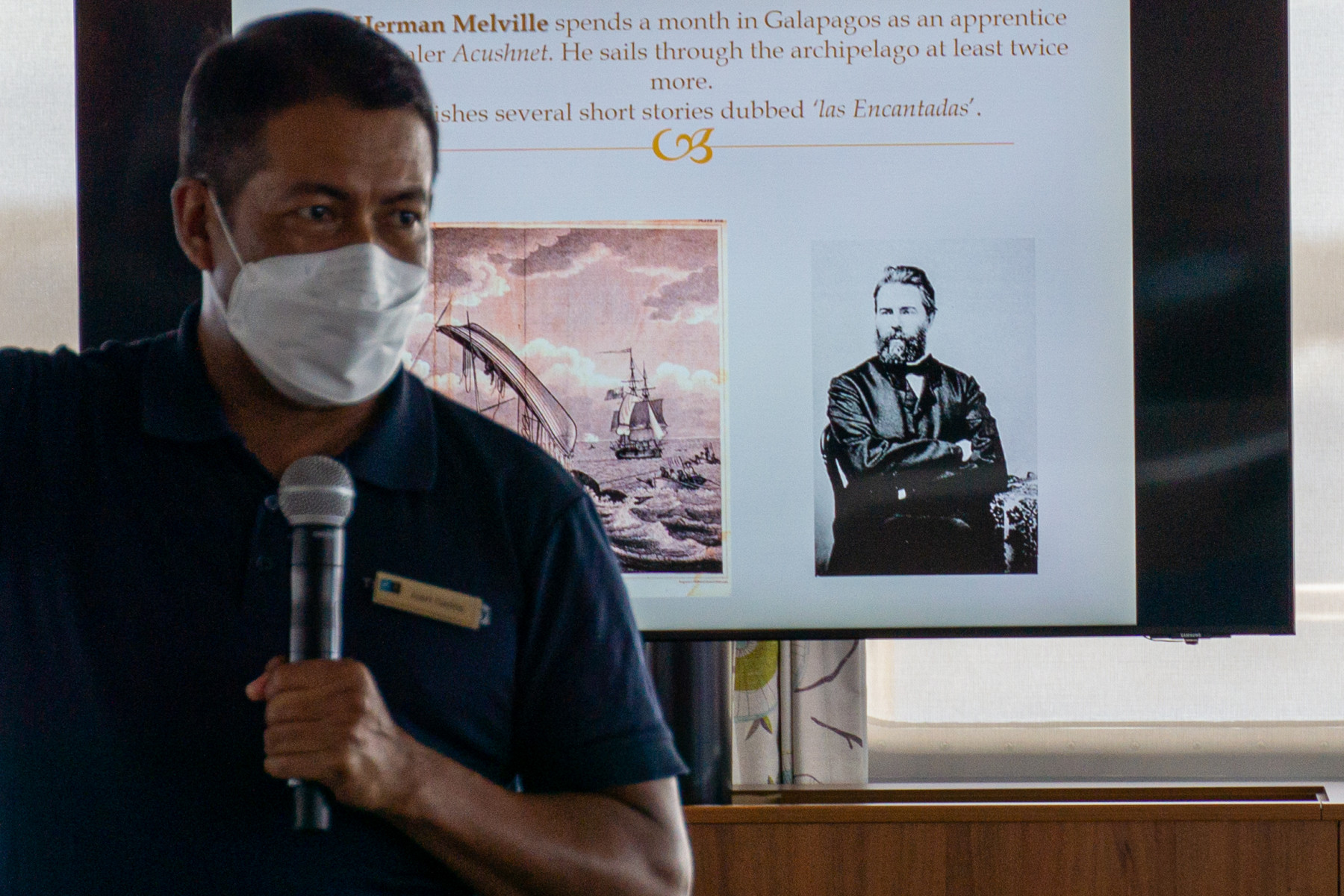

Juan Carlos Avila, a naturalist and expedition leader aboard the National Geographic Endeavour II, is also a farmer. (Photo courtesy Juan Carlos Avila)

Juan Carlos Avila, a naturalist and expedition leader aboard the National Geographic Endeavour II, is also a farmer. (Photo courtesy Juan Carlos Avila)

In 1989, when Juan Carlos Avila was 11, he and his family moved to the Galápagos Islands to work on his father’s cattle ranch.

“We were kind of bored in the beginning,” Juan Carlos says. “Back in those years the trails weren’t paved. You had to walk across lava rocks to go anywhere so we always came home with bruises and injuries on our knees.”

Earlier in his childhood, Juan Carlos grew up in the vibrant cloud forests of mainland Ecuador. The region is considered one of the single richest biological hotspots on the planet. Juan Carlos could recall walking through the forest spotting a seemingly endless number of colorful birds, monkeys, and armadillos. When he moved to the Galápagos Islands, all he could see in the surrounding highlands of Santa Cruz Island were just some dark colored finches. Little did Juan Carlos know at the time that these very same finches helped Charles Darwin produce his theory of evolution, which changed the way in how we all understand the natural world.

Even Darwin shared similar thoughts when he first landed on the Galapagos 154 years before Juan Carlos: “Nothing could be less inviting than the first appearance. A broken field of black basaltic lava, thrown into the most rugged waves, and crossed by great fissures, is everywhere covered by stunted, sun-burnt brushwood, which shows little signs of life.”

Juan Carlos recalled the moment when he changed his mind about life on the enchanted islands after seeing a giant tortoise for the first time. “I couldn’t believe these big things could walk! When we were kids, there were no TVs and no electricity, so we would just get close to the giant tortoises and watch them for hours!”

As a kid growing up on the Galápagos Islands, Juan Carlos didn’t have the same access to what the tourists would see. That all changed when he won a voyage on a ship in high school to visit several other islands.

“Everything was different to me, beginning with the rocks,” he says. Before his famed voyage on the H.M.S. Beagle, Darwin was a disinterested medical student who later found his pathway into naturalism through geology. Darwin, too, made careful observations about the geological differences within the Galápagos Islands.

“When I arrived at North Seymour Island for the first time, I started to compare how it was different from Santa Cruz,” Juan Carlos says. There, he could see vast colonies of frigate birds with their characteristic red pouches, blue-footed boobies engaged in courtship rituals, and land iguanas scattered across the decorative landscape.

“I was like, ‘Oh my God! Everything is so different from Santa Cruz!’”

As Juan Carlos continued his journey to the islands of Espanola and Floreana, he started to learn more about the human history of the Galápagos. Well before Juan Carlos’s family, and even before Darwin himself arrived, many pirates, whalers, and naturalists paid the archipelago a visit. “They paved the road for people like my family to eventually come and do farming,” says Juan Carlos, who also now owns a farm on Santa Cruz Island, like his father before him.

After graduating high school, Juan Carlos was set on becoming a mechanical engineer on a boat, before stumbling on an opportunity to become a naturalist guide. “Once I became a naturalist, I realized this is what I wanted to do (with my life),” he says.

Juan Carlos has now been a naturalist guide with Lindblad Expeditions for 16 years. As the Expedition Leader aboard the National Geographic Endeavour II, he enjoys working for a company like Lindblad that is deeply and actively involved in the conservation of the islands. “It’s not like we just operate here, bring visitors, take photographs and then they go away. It is about bringing visitors who would like to do something to preserve these natural places,” he says. “They want to be a part of long-lasting change, and that’s what I like about this company. That is why I am here.”

To Juan Carlos, the job of a naturalist has changed a lot since the days of Darwin. “Back in those years of exploration, during the time of Darwin, a naturalist would catch and shoot animals, do taxidermy, and sell their specimens to museums and universities as a type of business,” he says.

Today, a naturalist must be a permanent resident on the Galápagos Islands. They no longer catch and kill animals; instead, they must keep visitors from disturbing them. “Today, the connotation of a naturalist is something different. They must be somebody who knows a lot about nature, biology, and geology. They must embody the spirit of conservation and be good at passing down the messages and concepts of natural history,” Juan Carlos says.

While the Galápagos Islands face several threats like climate change and invasive species, naturalists like Juan Carlos are working hard to ensure their home can continue to inspire future generations who wish to visit and conserve these enchanted islands.