Paul Leoni

Paul Leoni

In Maine, lobster is more than a meal. It is the lifeblood of the state’s coastal economy, accounting for tens of thousands of jobs and $464 million in revenue in 2023. Yet, climate change threatens the viability of lobster populations in these productive waters. In particular, changing ocean currents are making the Gulf of Maine warm three times faster than the global average, or faster than 99% of the ocean.

Rapid ocean warming poses existential challenges to Maine’s largest commercial fishery. Stress induced by rising temperatures can make lobsters more susceptible to shell disease, compromising their ability to reproduce successfully. In warmer waters, tiny copepods eaten by larval lobsters are growing smaller and shifting their seasonal migration patterns. This results in less nutritious food for baby lobsters, greater mismatch between lobster larvae release and food availability, and fewer juveniles surviving into adulthood. In the wake of these changes, experts predict that lobsters will increasingly seek refuge in colder, deeper waters and migrate northward toward Canada.

Transcript: Generally, we are seeing a pattern of lobster shifting further into the northeast region of the Gulf of Maine into cooler, deeper waters during certain life stages. But, that doesn’t necessarily imply that they’ve all migrated there or moved or marched up from southern New England. It will be more about redistribution of where lobsters are more available, which relates to how readily some people compared to others can capitalize on those different changes. And perhaps abundances returning to early or mid-2000s landing levels rather than staying at that peak that we have known in more recent years.

Kat Maltby, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Research Associate in the Integrated Systems Ecology Lab at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute (GMRI).

Notably, ocean warming has supported a boom in Maine’s lobster industry and a bust in southern New England. In the Gulf of Maine, temperatures have become optimal for lobster reproduction and species range shifts have contributed to record commercial catch. Yet, experts predict that rapid warming will only exacerbate the volatility of Maine’s lobster industry, posing novel challenges to fishers and business owners to adapt alongside the shifting crustaceans.

Ivan Bly started lobstering in Midcoast Maine when he was young. Today, he hauls commercial traps from the Iris Irene, a boat named after his grandmother, Irene, and 12-year-old daughter, Iris. Alongside her father, Iris has been lobstering her entire life. “We’ve had her out here before she remembered. We used to put her in a lobster crate,” Bly said.

Bly lobsters out of Tenants Harbor, where his state commercial fishing license allows him 800 traps within an established fishing zone. State and federal licenses are coveted and scarce in Maine, requiring extensive apprenticeship, extended processing times, and expensive permitting costs. Those born into the lobster industry are entering increasingly precarious waters, where rigid rules and regulations preoccupy fishers and lack adaptive measures for climate impacts.

Bly recognizes ocean warming and its contribution to Maine’s lobster boom. He also knows the challenges and costs of fishing in deeper waters. “When you go further out, it costs more money, and it’s a bigger risk. You need bigger rope, heavier, bigger traps,” he said.

Yet, faced with the annual volatility of a dynamic industry, his anxieties are resigned to the short-term: “I think we’ll kill the industry with chemicals and nonsense before that. Warming is the least of my concerns. When the water warms up that much, I’ll be long gone.” For Bly, “nonsense” includes the environmental and economic costs of chemical pollution, offshore wind development, and inconsistent rope and trap regulations for North Atlantic right whale protection.

Contributing to Bly’s focus on pollution and regulation is the rigid territoriality built into the culture and permitting of the lobster industry. While a commercial fisher can move their traps within a permitted zone, they risk retaliation and violence from encroaching on another fisher’s territory.

According to Bly, “You’d be welcomed with shotguns and knife blades” if you messed with another’s traps. Notably, a state license prohibits fishing in federal waters further offshore and can rarely be transferred to a different zone within state waters.

In this rigid framework, fishers like Bly cannot follow lobsters into northern, deeper waters beyond where their permit allows. “The fishing grounds do move. Different areas have had great fishing and hopefully, we get our turn. But, you gotta fish where you live,” Bly said.

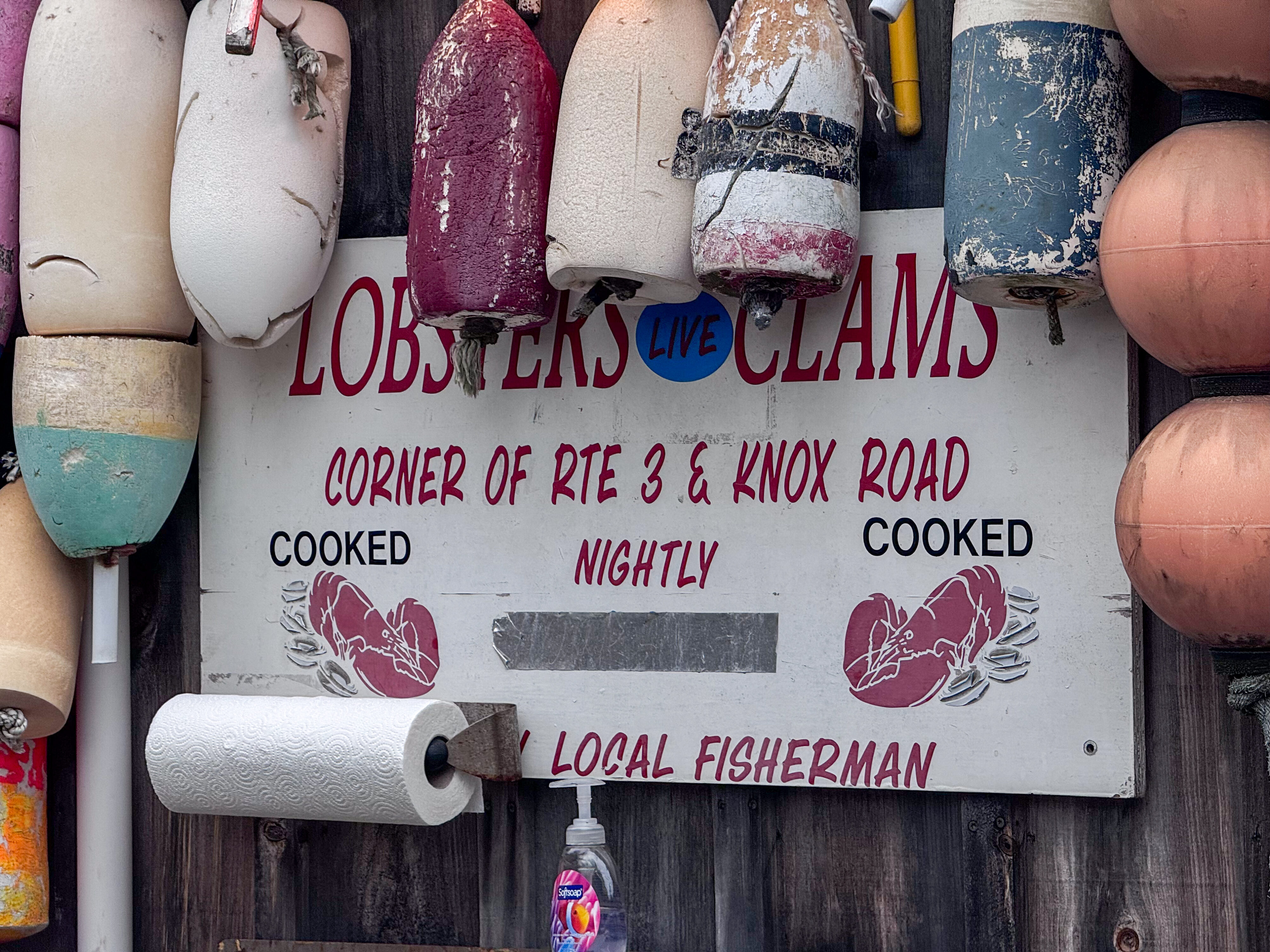

In Maine’s coastal economy, changes in the water directly affect livelihoods on land. In Bar Harbor, Patti Staples is the owner and manager of the Happy Clam Shack, where hand-picked meat is enjoyed by consumers in iconic lobster rolls.

Since 2015, Staples has operated a sea-to-table business that values quality over quantity. To do so, she buys catch directly from local fishers and picks the lobster meat in-shack each morning. Having experienced increased costs, decreased tourism, and supply chain shortages during the pandemic, Staples sees ocean warming as another existential threat to her business and local suppliers.

“If they don’t have their product, we don’t have their product, and the families don’t have their product. If the Gulf doesn’t stop warming up, they’re going to crawl into Canada,” she said.

Profit and catch in the lobster industry fluctuate with consumer demand and market price. For instance, in 2023, Maine experienced its lowest lobster haul in 15 years, as inflated fuel and bait costs disincentivized fishers to get on the water. Yet, the second-highest price ever recorded ($4.95 per pound) contributed to a noticeable rebound from lower profits in 2022.

Ocean warming will only exacerbate these unpredictable boom and bust cycles. As warming decreases regional productivity and increases operational costs, per-pound prices will reflect the increased effort and resources needed for fishing in deeper waters. As a result, Staples anticipates higher costs for herself and her customers.

Transcript: Unfortunately, we will see the prices go up. We won’t see as many businesses like our lobster pound being able to sustain if we don’t have a product. If it gets too costly, a lot of people — the families we want here to enjoy our lobster — won’t be able to afford it. And if our fisherman aren’t catching their product and they are paying all this money for their sternmen, their gas, their bait, how are they going to be able to sustain also? It’s scary. We don’t want to see our product leave.

Patti Staples, owner and manager of Happy Clam Shack

Since ocean warming intersects with the economic and regulatory challenges facing fishers like Bly and business owners like Staples, climate adaptation is an opportunity to build a more resilient, productive, and profitable industry. At the Gulf of Maine Research Institute (GMRI), Kat Maltby, Ph.D., studies the social resilience of imperiled fisheries to inform adaptive planning in Maine’s lobster industry. To her, adapting to warming waters requires a holistic management approach in collaboration with industry, government, and the scientific community.

Transcript: There’s an opportunity for us to be more integrated in joining efforts to think more holistically about supporting resilience. When we talk about adaptation strategies, we need to talk about that in the context of all the other issues the industry is concerned about and think holistically about the future needs of the fishery and the industry together. Just thinking about climate change in a silo risks maladaptive strategies or implementing strategies and solutions that might not work as effectively or successfully because there are other drivers of change that haven’t been considered.

Kat Maltby, Ph. D., Gulf of Maine Research Institute

For fishers, she emphasizes empowering a sense of agency over diverse livelihood options, including:

Maltby upholds that the burden of adaptation should not be on fishers alone. She contends that all levels of the industry must adapt simultaneously. This includes changing processing and handling capacities in the supply chain in order to enable diversification into other fisheries.

She also recommends maintaining working waterfronts that protect coastal properties for commercial fishing and aquaculture use. Lastly, Maltby supports the creation of more flexible permitting structures that incorporate information and decision-making from lobster fishers like Bly.

While lobster redistribution is inevitable in Maine’s warming waters, fishers already follow strict sustainable fishing standards that support stable, resilient lobster populations in the Gulf of Maine. These practices include notching the tails of egg-bearing females and measuring catch to ensure small juveniles and large, reproducing lobsters remain in the water.

Transcript: Ivan: Is it a boy or girl? Iris: Girl. Ivan: Does it have a V-notch? Eggs?

A GMRI study found that the lack of protections on larger reproductive lobsters in southern New England made the population less resilient to warmer waters, contributing to its collapse. On the contrary, conservation measures in the Gulf of Maine supported a lobster boom and can mitigate expected productivity declines. Given Maine’s lobster fishery is already resilient due to sustainable management, Maltby sees hope and opportunity for the broader industry to operate in warming waters. “It’s not all doom and gloom. This really provides us an opportunity to think about the kinds of futures we want.”

Transcript: Climate change is a very big risk and has a lot of impacts now and will continue to have for many coastal communities in Maine. But, it is not all doom and gloom. This provides an opportunity for us to think about the kind of futures that we want and think about the processes that allow us to get there. Drawing on more innovative and creative ideas and solutions. Really connecting people who haven’t necessarily been able to exchange ideas and information before. It doesn’t have to be such a gloom-and-doom narrative.

Kat Maltby, Ph. D., Gulf of Maine Research Institute