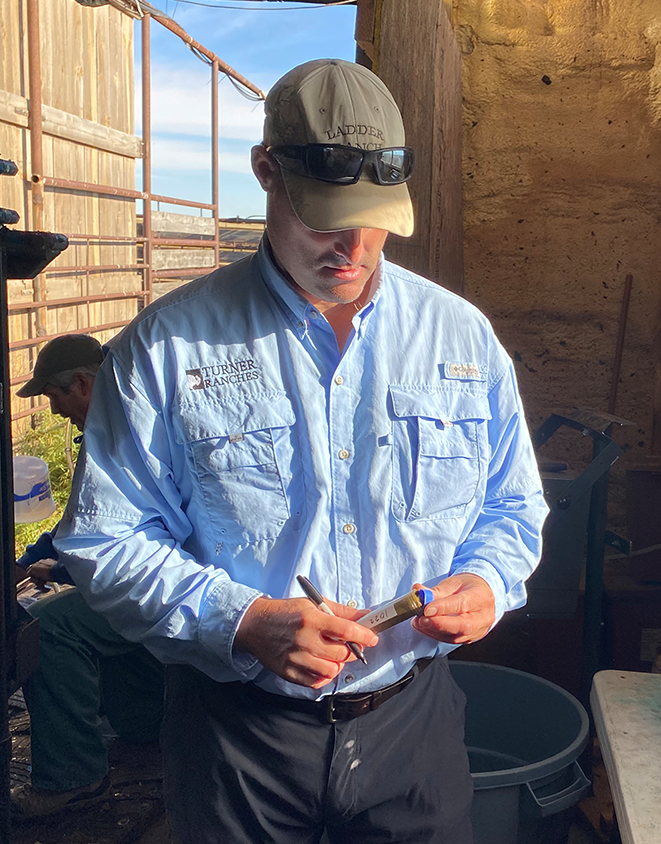

Tyrell McClain holds up a clump of soil on McGinley Ranch while discussing the high biodiversity under the surface of the ground on September 17, 2022. (Dr. Imani Cheers/Planet Forward)

Tyrell McClain holds up a clump of soil on McGinley Ranch while discussing the high biodiversity under the surface of the ground on September 17, 2022. (Dr. Imani Cheers/Planet Forward)

In the Midwestern strongholds of American agriculture, a tipping point creeps closer. Flashing past seas of rolling hills, fields of tilled soil, and towering pivot irrigation systems, Mark Kossler rounds off a trio of trucks making for the 80,000-acre inflection point deep in Nebraska’s Sandhills. Twenty minutes of kicking up dust on a one-lane gravel road, and he pulls into McGinley Ranch: the first of Ted Turner’s ranches to be transferred to the Turner Institute of Ecoagriculture.

Here, Kossler is at the top of the food chain. As the vice president of ranch operations at Turner Enterprises (TEI), Kossler oversees all 15 ranches in Turner’s 1.85 million-acre land empire and the 45,000 bison on them – the largest private bison herd in the world. Growing up in the 1960s on a ranch in Colorado, the experienced rancher is a living witness to over six decades of change in agriculture and the communities it sustains. With the rise of what he calls “additive agriculture,” Kossler has seen farmers and ranchers grappling with declining profit margins, degrading land quality, and an exodus of youth from the industry.

He explains that additive agriculture stems from the intensive use of chemical additives – fertilizers, pesticides – to increase monoculture agricultural yields. The results? Short-term gains that compromise ecological integrity and long-term profitability. It’s a model where man allegedly triumphs over nature, and an industry standard that the Turner Institute of Ecoagriculture is challenging.

According to the TEI mission statement, Turner Enterprises has always had a triple bottom line of economic sustainability, ecological sensitivity, and conservation. The company’s goal is still profit, “but not at the expense of nature,” Kossler said with emphasis. This “balance of conservation and commerce,” as Kossler calls it, pushed TEI toward implementing more holistic land management practices. Years later, Kossler finally matched TEI’s guiding principles with a name: regenerative agriculture.

Unlike additive agriculture, regenerative agriculture is a set of practices that focus on maximizing productivity through restoring ecosystem services, like building healthy soil microbiomes, enhancing carbon sequestration and water infiltration, and supporting native ecosystem biodiversity. The connection was instant, Kossler said, “I just knew this was the next step for [TEI]. We were already doing a lot of it, but there was more we could do…it became a mission in our company.”

As a result, in 2021, Kossler and the team at Turner Enterprises founded the Turner Institute of Ecoagriculture as an Agriculture Research Organization dedicated to “researching, developing, and disseminating sustainability strategies and techniques for conserving ecosystems, agriculture, and rural communities,” according to the Institute.

Driving across McGinley Ranch is evidence that principles of regenerative agriculture have been embraced with open arms: Pastures are divided uniquely to support high-intensity grazing, the lush meadows are grazed instead of hayed for the winter, and two fleeing prairie chickens signal a rebounding endangered population. The ranch aims to “lead by example” in the agriculture industry, turning a profit off the land while also actively supporting its regeneration. Their products, Kossler said, are of higher quality as a result of it.

Still, there are profound challenges ahead for the transition to more sustainable agricultural practices.

“Change is fearful,” Kossler said, especially when there is a way things have always been done culturally ingrained in the agriculture community. “Many are more comfortable doing something that’s not really working well,” he said, and what they’re doing is often reinforced by a higher education system that supports industrialized additive agriculture. “What we were taught was only half of the story – one side of a two-sided story. I feel as though I was only told half of the story.”

Financially, farmers and ranchers can also be put in a tight spot if they are seeking to transition. Despite long-run increases in yield, the tight margins in agriculture can make it hard to front the initial cost of switching to regenerative practices due to upfront costs like fencing and the “three-year trough,” or a time of lower production while natural systems adjust to new agricultural practices. It can be a hard sell, and many “hardcore ag producers are skeptical,” Kossler said, especially older generations.

But in the fertile soils Kossler and his team are growing, they’ve cultivated more than prairie grasses and carbon sinks: Change is taking root. As the outliers in the equation, McGinley Ranch and the Turner Institute of Ecoagriculture have been in the business of influencing others to create “synergies” for change. “We’re kind of herd animals,” Kossler said, and like bison, once some go, others will follow.

In the Sandhills, the dominoes have already begun toppling. After watching, then inquiring about the success of McGinley’s regeneratively-managed pastures, a nearby rancher has adopted what ranch techs McGinley say is the uncommon practice of grazing meadows instead of haying them for the winter. Partnerships between the Turner Institute of Ecoagriculture and research institutions, like South Dakota State University’s Center of Excellence for Bison Studies, are changing the traditional understanding of agriculture in academia and adopting regenerative approaches.

Perhaps most importantly, younger generations are buying in. Jessica Lovitt, McGinley Ranch’s primary Range Data Specialist, is one of them. Like many in agribusiness, Lovitt started with very traditional cattle ranching on her family ranch. After coming to McGinley, she admits to harboring doubts, having “never seen things done [differently] before.” Despite her reservations, she said, “the results speak for themselves,” and credits her traditional background for pushing her to ask more questions. Now, she offers others the same advice: “Get out and go see it for yourself…give it a chance. Ask the questions.”

Lovitt embodies a critical generational transition that McGinley is investing in to help turn the tides: Educating the younger generations helps bring viable paths of integrating regenerative practices into family agricultural operations. As the Turner Institute takes on more young staff and interns, Kossler is hopeful that they will “go home and make some changes,” and the pace of progress will quicken.

Together, Kossler and Lovitt hope that private and government support can help alleviate the financial barriers for agricultural communities seeking to do right by themselves and by the land they live off. Both are optimistic that 10 years from now, the rolling sandhills of Nebraska will have healthier soils, pastures, and communities.