Green Corn’s grand gardeners

The first thing Renee Studebaker did when she showed me the Smith Elementary School Garden was tell me who planted what. “Elijah planted the carrots,” she said, fingering laced carrot fronds that stuck from the sandy soil. “David planted the beets.” She told me the names of these third-graders in her after-school garden class with such affection that I almost began to feel that I knew them myself. Each plant paired with a painted wooden label. One had polka-dots; others had rainbows and stripes. The crops themselves made a colorful display: bunches of broccoli bloomed yellow; white cauliflower heads grew heavy; yukon golds abounded. I wondered briefly if the kids painted their impression of the plants’ personalities on that wooden canvas.

It was a windy, bright afternoon in March when I visited the Smith Elementary in south Austin. The first thing that struck me was its size. Upwards of twenty beds — some wooden, some cinder-block, some stone-cobbled, surrounded a large shade structure and a picnic table. Invasive bermuda grass gained a firm grasp on many beds, and many shrubs were brown from February’s freeze. “I’ve got lots of weeding to do out here, obviously,” Studebaker said, scrutinizing her domain. I, on the other hand, was enchanted. Mustang grape vines with brown, gnarled stems surrounded the fenced-off garden. Bumblebees buzzed lazily between dandelions. Pear and apple blossoms yawned open in the warm air. Studebaker told me that last fall, pumpkins plants from discarded Halloween seeds overran the garden’s compost pile. When I visited, the grapevine was beginning to green, and so were many of the seemingly-dead plants. Studebaker would pull back brown stems, and with a “wait wait wait is it green?” or a “okay, look at this!” point out barely-visible green popping from the plant base. I felt like I’d stepped into Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Secret Garden: “It seemed almost like being shut out of the world in some fairy place.”

***

The Smith Elementary School Garden is one of hundreds of gardens that a nonprofit group called the Green Corn Project has implemented in Austin over the 23 years of the nonprofit’s existence. “I always like to say that Green Corn was urban gardening before it was cool,” said Brooke Leterelle, Green Corn’s program coordinator. Thinking back on the hundred of beds raised by the organization, she added, “That’s a lot of good-feelin’ stuff –– a lot of food. It’s a lot of happiness.” Green Corn’s garden clients come from all stages of life — from senior citizens to parents to preschoolers. But what their clients all have in common is that they have difficulty accessing fresh, healthy food. “We’re growing food in a food desert, basically,” added Leterelle.

A food desert is a place where people don’t have access to fresh produce –– whether it be in a low-income city neighborhood surrounded by fast-food stands, or a rural town without stocked grocery stores. This may lead many to suffer from life-threatening diseases such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes. Studies have shown that food deserts disproportionately affect low-income and minority populations. According to a study at the University of Texas at Austin, access to reliable transportation plays a big role — in auto-centric Austin, families without access cars are especially vulnerable. Green Corn sought to shift that paradigm. “It’s harder to change larger systems,” said Leterelle, but “Green Corn dives right in there… The repercussions are multiplied with a successful garden, because it makes you feel good, the healthiest food that you eat is the stuff that you grow and you’re not paying money for it.”

The Green Corn volunteers directly target their clients, setting up booths at other nonprofits like the Central Texas Food Bank and Coats for Kids. There, Green Corn volunteers are able to explain their mission and potential clients have the opportunity to fill out a garden request form. Then, each spring and fall, volunteers set out to about 50-60 sites per season for “dig-ins,” where they amend existing gardens and create new ones –– turning “grass to garden,” as Letterele puts it.

“I think the hardest part about gardening is the starting part,” she said. “I like that we come in and take that off their plate.”

The benefits to their clients have been astounding. Some have been with Green Corn for years, and are now gardening experts, feeding their family and neighbors. Letterele has become a close friend of many clients, and through building a community, she is able to lift up those around her. Letterele told me of one mother she worked with a few days ago who didn’t know what a seed looked like. A few hours later, she was pressing lettuce seeds into the earth, and telling Letterle all about it. “It’s that simple education –– those simple things that just click once you have a little bit of information… It makes people happy to have their hands in the dirt and to watch something grow. You get to care for something.”

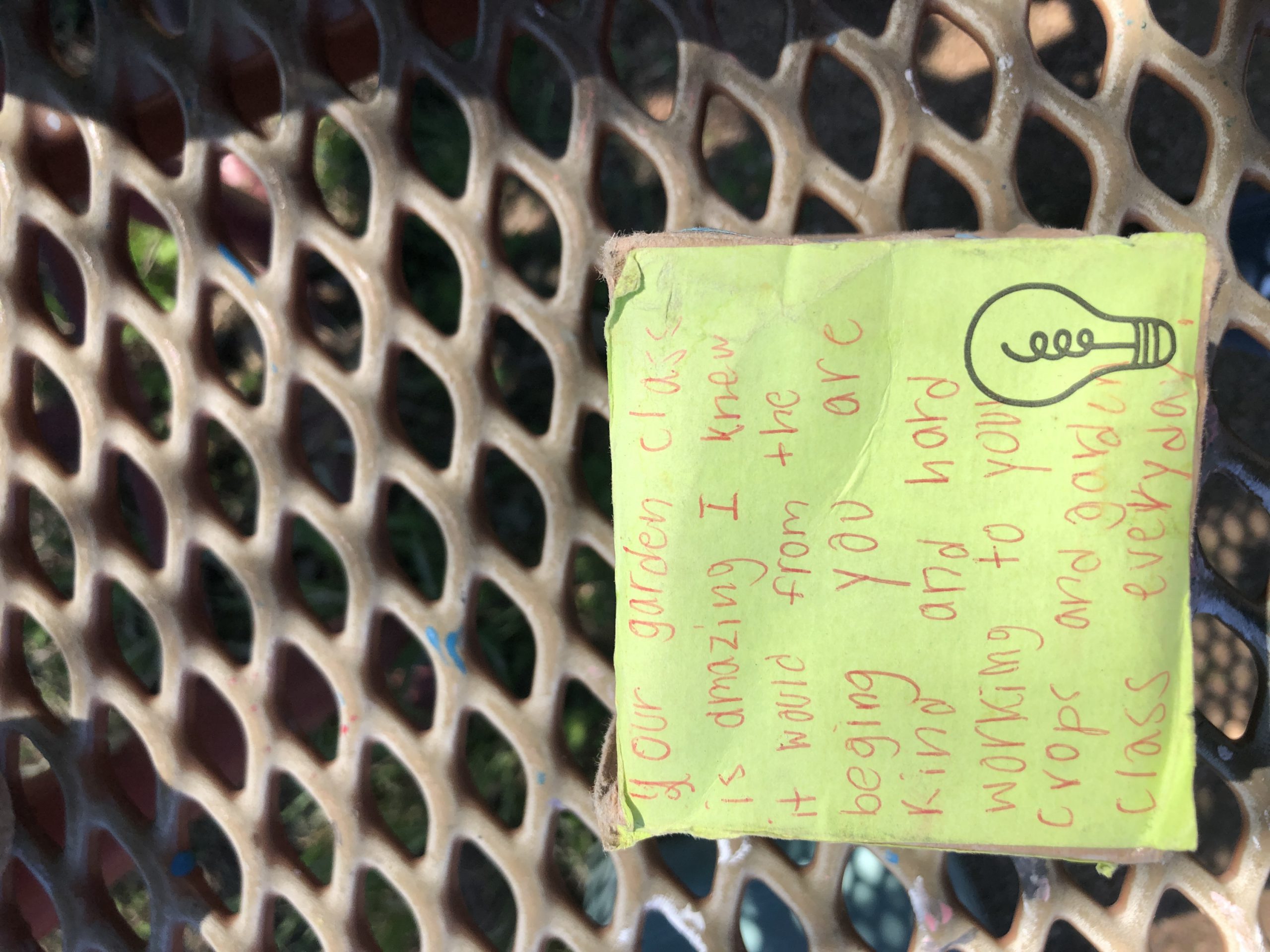

Perhaps the most compounded benefit of Green Corn comes with school gardens. “Those gardens that reach multiple people –– the wonderful impact of them is just magnified,” said Letterele. Green Corn has helped install over a dozen school gardens in the Austin area. Studebaker serves a dual role as both a Green Corn volunteer and an after-school teacher at Smith, a role she acquired after Green Corn became involved with the school. In the after-school program, she teaches students about everything from seasonal plantings to monarch migrations to the ethics of reduce, reuse, and recycle. They collect bugs, cook healthy food, and examine wildlife scat (hopefully not while cooking). “It gives them a chance to learn more about the outdoors and wildlife and the various little beings that we all share the planet with,” said Studebaker.

“We’re in a place where we’re wanting to do some growing and expanding,” said Studebaker, “Getting more involved with helping create local food systems in low income communities.” Green Corn is looking to pair with The Training Kitchen, a community-hub in south Austin, and work with them to create an even bigger demo-garden in which to train their volunteers. They hope to expand their client-base even further, reaching even more low-income homes and schools. Letterele also aims to check in more regularly on their clients. “Starting out… is one thing, but confidently gardening is another. We want to be there to make sure that our gardeners are confident… solving problems before they even have them.”

**

When the Green Corn Project was first starting out in the late ’90s, one of the founders happened upon an article about a Creek Indian celebration called the Green Corn Festival, held once a year when the first green shoots of corn appear in spring. It is a way of thanking Mother Nature for last season’s harvest, and of celebrating the sight of new growth in spring. “As gardeners,” said Letterele, “We’re supporting life and little ecosystems. So I think it’s a very well-rounded name for us.” But Studebaker wasn’t so sure. “We need to at least be growing some corn somewhere!” she exclaimed. “How can we be called this and we never plant corn?”

That March afternoon, Studebaker and I decided to do just that. We got two packets of corn seeds and went to work. The wind had died down, and I could feel the cloudless heat pressing on my neck. I filled my left hand with shriveled yellow corn seeds, and with my right, I created a line-like crevasse in the earth. I pressed each seed six inches apart, then sprinkled them with a nutrient-rich compost mixture. A mocking bird warbled away, watching us as we worked. Studebaker mentioned that after years spent in the same garden, animals began to recognize her. They’d keep her company as she reaped and sowed. I felt compelled, suddenly, to give thanks for this afternoon in nature’s fine blush of spring. I looked down at the corn kernel, golden-yellow and ripe with the promise of life, and pressed it into the earth.