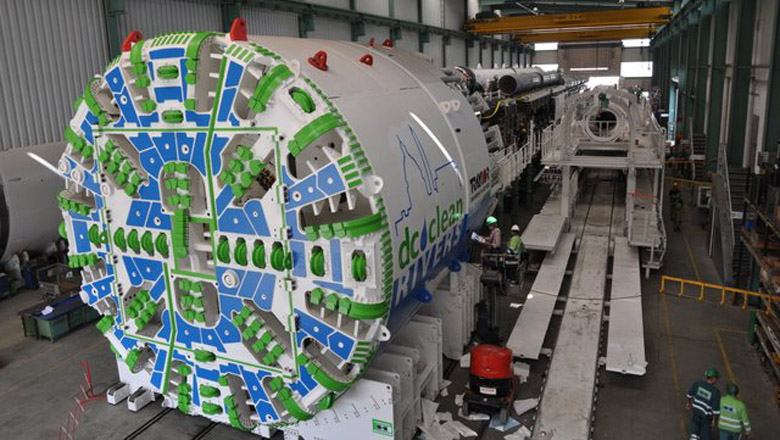

Cutterhead, shield and partial trailing gantries of the tunnel boring machine known as Lady Bird. (Photo courtesy DC Water)

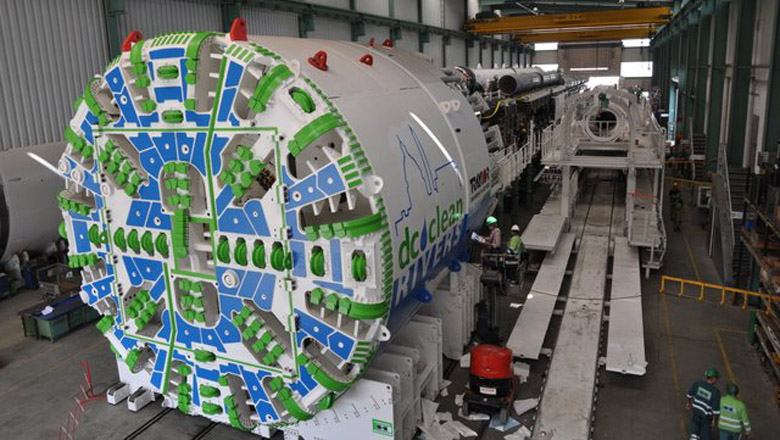

Cutterhead, shield and partial trailing gantries of the tunnel boring machine known as Lady Bird. (Photo courtesy DC Water)

When her husband took office in 1963, Claudia Alta Johnson, better known as Lady Bird, made it her mission to protect and preserve the environment. She created the Committee for a More Beautiful Capital, whose effects can still be felt today, and helped call attention to the disgraceful state of the District’s rivers.

Now a giant machine, akin to a mechanical earthworm, denominated Lady Bird, burrowed deep under the city, creating a tunnel. This tunnel will serve to redirect sewage overflows, keeping the waste out of the city’s rivers on the occasions when the archaic sewage system becomes overwhelmed — a problem that has contributed to 3 billion gallons of raw sewage deposited into the Anacostia and Potomac annually.

This tunnel project is part of a larger commitment, $2.6 billion that D.C., along with the Environmental Protection Agency, has invested in a the Clean Rivers Project, a 20 year rivers cleanup initiative.

One report released by DC Appleseed, a D.C.-based organization focused on solving problems affecting the district and its residents, stated that the Anacostia river is one of the dirtiest in the country, practically unswimmable and for all safe purposes unfishable. Yet, the rivers are still a hub for D.C. life. People boat and fish in both of the city’s rivers, and the banks house parks, stadiums and other centers of activity.

Currently, the District’s sewer system dates back to the 1800s. It uses a combined approach, with one set of pipes for both sewage and stormwater. This means that with any storm that accumulates more than a quarter inch of rainfall, sewage flows into the rivers through 60 main overflow sites.

To give you an example of the extent of the problem, the highest rate of overflow for the last quarter of 2015 was the Northeast Boundary Swirl Effluent Combined Sewer Overflow. There were 10 overflows in the quarter, which equaled spillage of 128.66 million gallons of sewage and flowed for just under 80 hours. To put it in perspective, this is enough sewage to fill just under 195 Olympic swimming pools.

It’s estimated the new tunnel will cut those sewage overflows by 96%.

The machine used to create this tunnel is known as a Tunnel Boring Machine, and consists of a cutterhead, scrapers, a giant screw and a conveyor belt. Lady Bird is 442 feet long (more than a football field in length, according to DC Water), weighs 1,325 tons, and can move at a speed of 4 inches per minute.

To travel forward it braces itself against the sides of the concrete tunnel behind it and uses hydraulic jacks to propel itself forward as the cutterhead slowly rotates. The earth is loosened and mixed with a soapy, conditioning substance. It is then sucked into a giant screw which turns, carrying the muck to a conveyor belt, where it travels out of the tunnel to be disposed of at a dumping site.

After each push a new section of the tunnel is put up by workers, who make use of a mechanical arm to fit the pre-made sections into place. As the next shove occurs, grout is injected between the new tunnel and the outside dirt. Workers lay down rails so the next section of tunnels can arrive and the cycle continues.

While Lady Bird has completed her section of the tunnel, as has a machine named Lucy Diggs Slowe, named for one of the founders and first president of Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, and later an administrator at Howard University. Two other machines will continue to work. The third tunnel boring machine, named Nannie after Nannie Helen Burroughs, a civil rights activist who was very prominent in D.C. and helped provide education for African-American girls. Nannie is digging the portion of the tunnel near RFK Stadium, which will connect to the tunnel that Lady Bird is working on. The fourth machine, a micro tunnel boring machine simply called Abigail, will connect Lucy’s tunnel to existing sewers.

These tunnels, when combined with urban sustainability and green infrastructure projects such as distributing free rain barrels to residents and replacing asphalt with a more porous pavement, green roofs and rain gardens. All of these, and other efforts combine in the $2.6 billion, 20-year Clean Rivers Project. In a decade, at the end of this initiative, District residents can expect to once again see rivers that are swimmable, fishable and compliant to the EPA regulations.