Fires of the future: Meet the Oregon innovators fighting global pollution with rocket stoves

Known as the “Grandfather of the Rocket Stove,” Dr. Larry Winiarski of Corvallis, Oregon, has spend most of his life “playing with fire” as he calls it. Raised in old mining camps that ran exclusively on giant sawdust burners, Winiarski spent his childhood building fires as a Boy Scout and his adult career investigating wood powered cars and jet engines. But it is his invention of a clean burning and super-efficient combustion device that has perhaps had the most positive impact on the lives of thousands of people in rural and developing countries.

The story of the rocket stove began in 1979, when Winiarski, a Ph.D. graduate in mechanical engineering, was working at the EPA. After his wife died in a freak traffic accident leaving him with three sons to raise, Winiarski made what he called a religious vow to dedicate the rest of his life to doing the right thing.

“I said ‘Lord I can’t handle this but if you somehow help me get through this, I’ll try to devote all my expertise, time and talents to where it will do real good in the world,’” Winiarski said.

His search for a cause brought him in contact with Aprovecho — Spanish for “to make best use of” — a non-profit based in Cottage Grove, Oregon, that was focused on improving cookstove technology for the approximately 3 billion people worldwide that still cook indoors over an open fire or traditional cookstove.

According to the World Health Organization, over 4 million people die prematurely due to indoor air pollution from cooking or heating with wood, animal manure, or coal.

“You go into places into places in South America and then they don’t even bother cleaning the walls because the next day it will be all be black again. The cobwebs are like stalagmites of creosote,” Winiarski said. “And the women has the baby on her back and they are breathing this all the time.”

Drawing on his childhood experience with efficient fire-making as well as his years as an engineer and scientist, Winiarski set about developing a set of basic stove design principles to improve combustion efficiency which became the origin of the rocket stove.

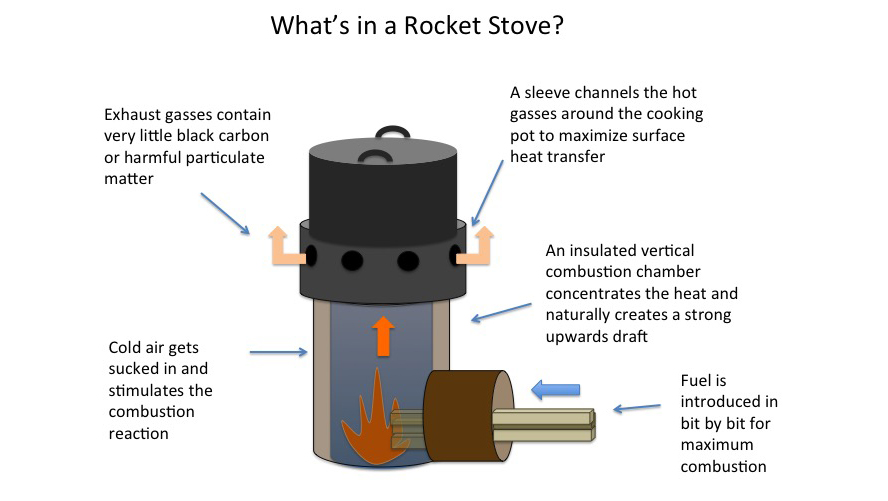

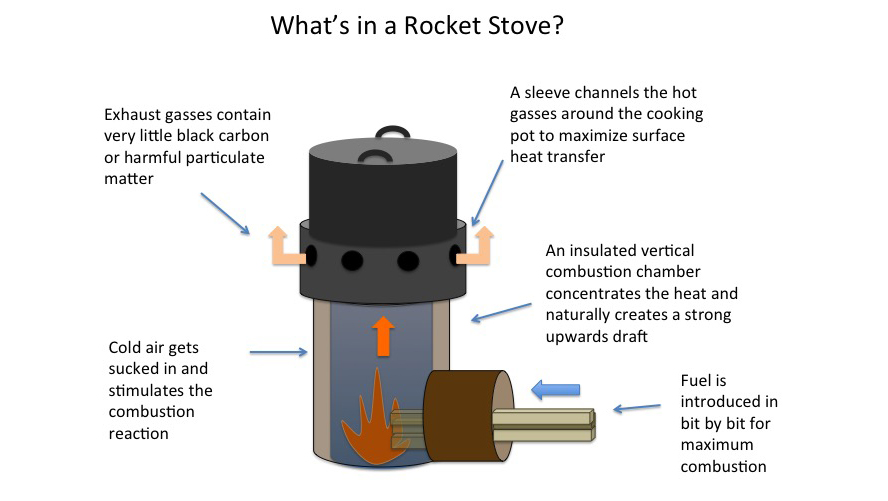

The key, Winiarski explained, is the insulated vertical combustion chamber which concentrates the heat and also produces a strong upwards draft from the warm air being drawn upwards. Another major component is that the fuel (usually wood) must be introduced bit by bit so all of the material burns efficiently without overloading the combustion process. Finally, a sleeve at the top of the stove circulates the hot gases rising from the fire around the cooking pot, maximizing heat transfer to the food.

These simple innovations put Aprovecho Research Center on the frontlines of a revolution in clean cookstove technology. Studies indicate that rocket stoves can reduce the amount of fuel used by 39% to 47% compared to an open fire, and can reduce emissions by about half what is produced by an open fire or traditional chimney stove. In many developing countries, using less wood is directly linked to decreased deforestation and the increased efficiency means that less CO2 gets released into the atmosphere. The higher temperatures inside a rocket stove also drastically reduce black carbon, a particulate component of wood smoke that is a large contributor to climate change.

Despite its many benefits, Winiarsky has never attempted to patent his rocket stove technology, insisting instead on open sourcing his basic principles to be shared, adapted and improved by stove makers and entrepreneurs around the world.

“I’m so proud that I’ve created local businesses for people that do a good job on the stoves,” Winiarski said.

Andrew McLean, chief operations officer at Aprovecho, explained the importance of having the rocket stove design be fluid and adaptable to fit regional cooking styles.

“In China all they want is high heat all the time because they are using a wok. In Mexico they’re boiling beans; so a low simmer for a very long time and they also need a griddle for tortillas,” McLean said.

“In Africa, they have a huge pot they’re making a very thick porridge in and they’re pounding the top of it all the time so they need a very durable stove that won’t break down from all the force.”

Aprovecho now operates 30 laboratories serving communities in 15 different countries around the world such as Nepal, India, Senegal, and China. Local rocket stove manufacturers can come to these labs and have their rocket stove prototypes tested for their efficiency and emissions level using the same technology which Aprovecho developed and uses in Oregon.

Every summer, Aprovecho also hosts a “Stove Camp” in Oregon where students and researchers from the international labs come and learn how to operate the testing equipment such as the emission monitoring hoods. Representatives of the U.N. High Commission for Refugees and the World Food Programs have attended these events in past years.

“This has advanced far beyond what I would have hoped for or I could have imagined,” Winiarski said.

But he’s not done yet. Besides his ongoing research into garbage incinerator and dehydrator designs, Winiarski is also working on an improved prototype of the rocket stove that uses double vortex directed airflow in the chimney to improve mixing of oxygen and fuel molecules and push the stove’s efficiency to new records.