Gladys Asu Ngouana

Gladys Asu Ngouana

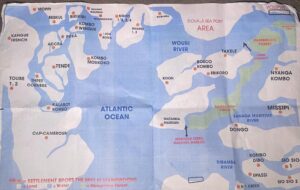

Potable water is a treasure and difficult to find in Cap Cameroun – an island perched in the Atlantic Ocean precisely in the Littoral region of Cameroon. It plays host to a population of about ten thousand, mostly fishermen immigrants from Nigeria and other neighboring countries. They stay in wooden flood-proof houses to protect them from the high tides experienced daily.

One of these residents is Eke Cynthia, a Cameroonian who was internally displaced by an ongoing secessionist war in the Northwest region of the nation. The young mother remains troubled with the sanitary conditions of the island and the consequences for her one-year-old baby girl.

The poor quality of water and hygiene has made water sources endemic to diseases like cholera and measles. “It is a bit challenging for us here with the nature of the environment and everything. No access to drinking water, lack of medical personnel and poor transport and health facilities. I suffered during my pregnancy and had complications. Now I fear for my child who is growing up,” said Cynthia.

According to the World Health Organization, “Between 29 October 2021 and 30 April 2022, a total of 6652 suspected cases including 134 deaths (case fatality ratio 2%) have been reported“ in the country. “We have been at the mercy of international non-governmental organizations like the Clinton Health Access Initiative and Doctors Without Borders. If not for their prompt intervention the cholera situation would have been worse,” said Pa Mbi Mathew, a community health worker.

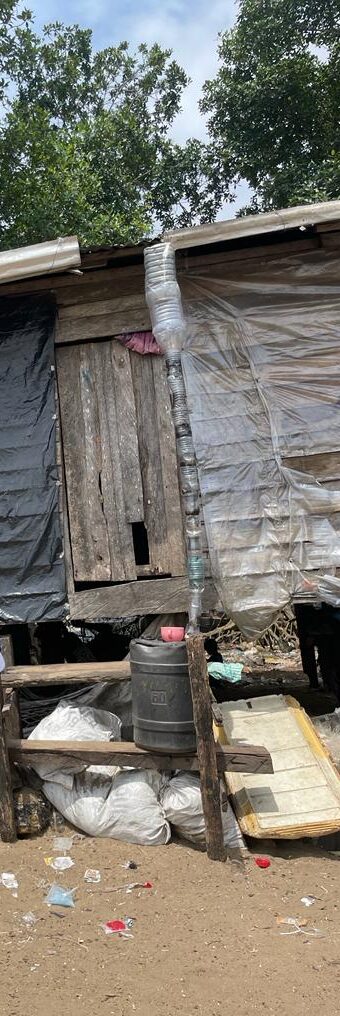

Cynthia and the rest of the islanders rely on rain barrels and the purchasing of potable water from the mainland, a two hour round trip by canoe. “In order to survive we buy water from Tiko and Douala in big drums of 200 liters and gallons of 20 liters and even mineral water in plastic bottles. The prices range from 400 FCFA (0.7USD) to 4000 FCFA (7USD) excluding transportation to and fro,” said Cynthia. The high importation of mineral water makes matters even worse with plastic bottles littered everywhere which are often washed away into the ocean.

Just when she thought things would be better in 2020 when the community tried digging a borehole, the project was met with failure. The project yielded only salty water, none of it was fresh enough to drink. So the next option was to make use of what she had, by collecting and conserving water especially during the rainy season.

Cynthia also uses imported plastic mineral water bottles, but instead of dumping these bottles, she recycles them into pipelines to collect water and fill the rain barrels. “After our disappointment in 2020, we decided to use plastic bottles to collect water rather than litter the environment with no proper waste disposal system. When we collect the water it can sustain us for the whole year especially those with more barrels,” said Cynthia. She is now more confident that her health and that of her daughter is assured as her environmental friendly measure to get drinking water reduces their vulnerability to waterborne diseases.

The practice of recycling empty water bottles makes her community an example of sustainability and care for the environment. As an activist in the community, Cynthia clings to a glimmer of hope that the government will come to their rescue as they continue surviving the storms.