A towering sand dune in Wadi Rum. (Farzona Comnas/George Washington University)

A towering sand dune in Wadi Rum. (Farzona Comnas/George Washington University)

When I went to see Denis Villeneuve’s “Dune,” I was expecting to be transported to an alien planet––but instead I was brought home. With an immediate Google search during the rolling credits, I learned that this sci-fi adventure does take place in the harsh environment that I grew up in. Oh Jordan, how I’ve missed you on the big screen!

If you don’t know much about the country, you certainly know what it looks like thanks to Hollywood location scouts. Most recently, “Dune” intensifies Jordan’s bare rocky landscapes and sprawling desert dunes to depict a water-deprived planet, but there are dozens of other well-known films that make use of the country’s remarkable scenery. Jon Stewart’s “Rosewater” captures the capital’s urban sprawl, “Lawrence of Arabia” shows off its beaches, and films such as “Star Wars: Rogue One,” “the Martian,” “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade,” and the 2019 adaptation of “Aladdin” take advantage of its most famous features: the Wadi Rum Desert and the city of Petra.

While most of my American friends’ first time camping took place in a wooded and stream-striped forest, I slept soundly in my sleeping bag beside a fire amongst beetles and scorpions. Instead of tackling a shrubby and rocky hill, my first hike was up a seemingly unconquerable never-ending sand dune. Even my first time at a dance party was during a fifth-grade class trip with traditional Jordanian drumming prompting us to hold hands and rhythmically skip around our campfire’s flames. I grew up in the Hollywood backdrop to alien and/or mystical societies and I feel an overwhelming sense of pride, nostalgia, and humor when I see it blown up and projected on the big screen. While Hollywood continues to portray a familiar and timeless, dry Jordanian landscape, I know from my annual visits and videos sent from my family that it now has an inconsistent and turbulent climate.

To assume that global warming makes the desert hotter and drier would be correct! The World Bank confirms that Jordan is at high risk for drought and research projects that Jordan’s average temperatures will increase from about +2.5°C to +5°C by the end of the century. With a water-scarce country that houses ten million citizens and three million refugees, Jordan’s leadership must implement water-conserving infrastructure immediately to save itself from future disasters. However, the cities continue to grow and urbanize amidst the warming climate, which creates more impermeable surfaces that flood with (rather than soak up) rainfall. Since water scarcity has been a major environmental challenge for time immemorial, much of the public and leadership overlook flash floods as yet another risk of a warming climate despite them claiming the lives of local children and threatening unknowing tourists. These floods make the country’s projected climate instability even more precarious.

Before expanding on the issue of flooding, it’s important to note that the information available is limited due to a low number of meteorological stations, as well as some research papers being published only in Arabic. Dr. Al-Raggad, a Jordanian hydrogeologist, said that only in 2016 the Jordanian government began monitoring precipitation in real-time, “but the historical data will remain as they are.” Regardless, basic climate science tells us that a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture, and in a desert setting where temperatures drop as soon as the sun sets, that water is expected to condense and fall. Another recently discovered phenomenon called an atmospheric river, may explain how warmer and wetter winds coming up from the African continent reach the dry Levant. Local researchers have concluded that in the “last two decades, the region has experienced a dramatic shift in its rainfall records patterns,” noting the series of floods that affected cities across the Middle East and North Africa over the past decade. In Jordan specifically, flooding events in the early 2000s affected less than 200 people on average, but in the last four years, the average has been over 200,000.

When Hollywood only comes to Jordan to film in its undoubtedly breathtaking desert landscape, it not only fails to capture how places like Petra now see destructive floods, but also how the country’s urban areas cannot keep up with the changing climate. These flash floods impact the cities as much as, if not more than, the desert. With growing refugee populations and limited funding, urban spaces grow larger with outdated flood systems and increased surface runoff. What can be done?

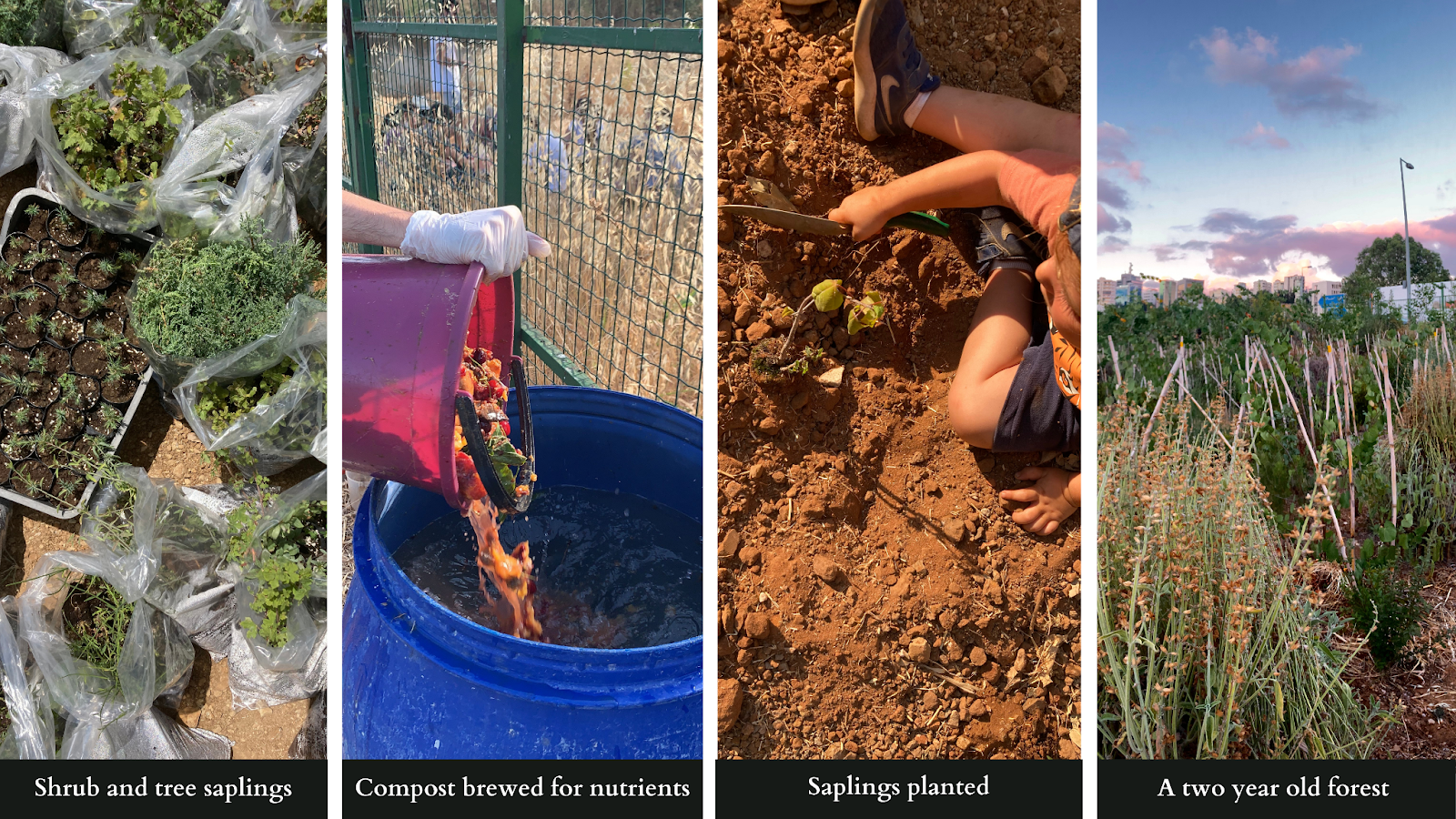

I was fortunate enough to travel to a nearby country to see how a driven group of urban foresters, theOtherForest, adapted to their changing environment. During the summer of 2021, I visited Lebanon and volunteered with theOtherForest which works on introducing “Miyawaki Forests” to neglected pieces of land. These forests, developed by the late Japanese botanist Akira Miyawaki, create green spaces that can absorb excess rain as well as provide shade for poorer and neglected communities. By planting native species’ saplings randomly and densely where there’s access to sun and water, within just three years of consistent maintenance the community will get a self-sufficient forest. It’s a process that brings back some of the greenery, biodiversity, and ecological services that a city typically erases.

As I walked through one of the young forests that had once been an abandoned lot, I couldn’t help but think about how I’d love to see this in Jordan. The Jordanian Government is putting in more resources into anti-flooding measures, such as teaming up with the Swiss Government and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation for risk mapping, but I wanted to know if this reforesting approach was taking root there. And I was thrilled to learn from the founder of theOtherForest that a similar group had emerged in Jordan called Tayyun. To prevent future floods and restore biodiversity, Tayyun found the powerful self-sustaining solution of urban foresting. These Miyawaki Forests serve as a green infrastructure method to 1. serve as a carbon sink where shrubs and trees pull carbon dioxide out of the air as part of photosynthesis, 2. create more habitats and encourage a return of biodiversity, and 3. restore degraded land and slow runoff from rain.

Looking through Tayyun’s Instagram page gave me the same giddy nostalgia as Dune’s grand cinematography did, except the former was the documentation of real heroic work being done in the region. In face of the highly damaging and deadly flash floods of the last decade, local leaders have looked to nature-based solutions to soften the devastation of extreme weather. While it’s fun to go to the movies and recognize my home, I prefer to go home and learn how people there are setting an example for resilience for all of us to follow.