Liz Kailies

Liz Kailies

In the middle of a solar panel array in North Carolina, the grass rustles with movement. A raccoon wanders between the panels. A fox wriggles through the permeable fencing and darts around the site. A cluster of turkeys stare accusingly into the wildlife camera. Eventually, a curious bobcat prowls outside the fence, slinking inside and outside of the site boundary.

The animal sightings were made possible by a carefully-placed camera trap used for conservation research. The project is part of efforts from the Nature Conservancy to investigate how solar development influences animal movement and work with solar developers to preserve the small corridors — or wildlife passageways — that allow for that movement.

The sight of wildlife lingering at a solar facility between crystalline panels is an unusual one. But in North Carolina, a state that ranks fourth in the nation for solar energy production and ninth for biodiversity, scientists and developers are realizing that the choice between renewables and biodiversity doesn’t have to be a trade-off.

Amid national efforts to decarbonize the U.S. energy sector and achieve current emissions reductions goals, the U.S. is increasing its buildout of renewable energy. In the last decade, the solar industry saw an average annual growth rate of 24%, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association.

As more and more renewables projects gain traction in states like North Carolina, biologists have raised concerns over potential impacts on wildlife populations, especially amid overdevelopment and fragmentation. Scientists have begun to research those impacts, but many studies have focused narrowly on bird deaths, habitat conversion, pollinator habitat, or soil ecosystems, with fewer insights on migration and movement specifically. With climate change exacerbating the need and scale of future migrations, this research gap is a pressing one.

While people often think of climate change as the biggest threat to biodiversity, the answer is actually habitat loss. Liz Kalies, the lead renewable energy scientist at the Nature Conservancy, spreads this message in her conservation work. “We can’t justify poor siting of renewable energy in the name of biodiversity,” said Kalies.

“But similarly, if we ignore climate change, that will also have severe consequences for biodiversity. So, we just really need to keep the two in our mind simultaneously, and not sacrifice one for the other,” she said.

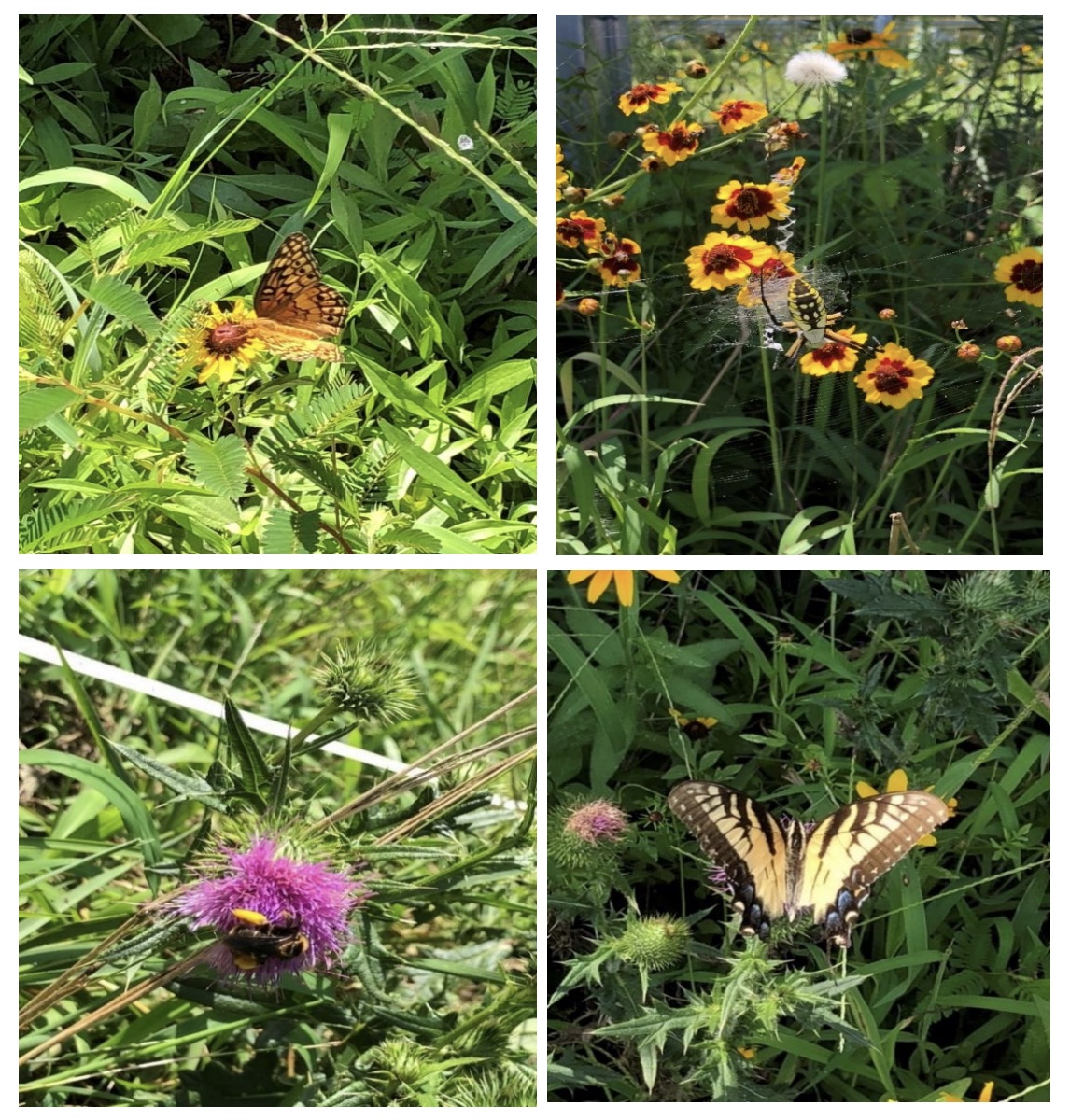

Fortunately, solar developers haves several options to avoid making those sacrifices: selecting sites responsibly (including repurposed mine land), building in wildlife passageways (small corridors to allow animals to pass through)—which could mean splitting a site down the middle—and letting nature reclaim parts of the facility by growing wildflowers, planting native species, or building pollinator habitats. A simple change, such as mowing the lawn in September or October instead of August, after breeding season, can make a difference, according to a research team in New York.

One of the most promising strategies so far is permeable fencing: swapping out traditional chain-link fencing for larger-holed fencing, which is meshy enough to allow small-to-medium sized mammals to slip through. Animal monitoring reports show the early promise of this fencing, as camera traps capture foxes, birds, and coyotes navigating around the fencing. In one study, wildlife-permeable fencing increased the probability that ungulates (hoofed mammals) successfully crossed through the fence by 33% — and they were able to do so in 54% less time.

Kalies and her team have launched several projects to study solar-wildlife interactions, including the camera trap project, direct site visits with developers, and even a bobcat-specific project. Kalies and her team are currently working on the latter, which involves locating, sedating, radio collaring, and tracking bobcats to generate visual maps of their meanderings. Bobcats are secretive, elusive animals who prefer uninterrupted vegetation, making them good candidates to study the challenges that animals may face in in solar landscapes.

Surprisingly, bobcats are interacting with the solar facilities. From the videos Kalies played, it appears some of them are even drawn to the facilities for unknown reasons. In their preliminary data, one bobcat appeared to cut through a solar facility that didn’t even have a permeable fence. The team hopes to increase their sample size of bobcats in order to predict impacts of solar buildout on their populations through simulation alone.

Sometimes, the answer is yes, according to developers. Medium-sized predators may help quell rodent populations, and rodents have been known to gnaw through the panels’ wiring, breaking the solar array.

Wildlife passageways offer other benefits to developers. At face value, building wildlife-friendly infrastructure is great for a company’s brand image and public relations — especially when local opposition to renewable projects is so prevalent, and sometimes stems from animal conservation concerns. Additionally, installing wildlife-friendly fencing is economical, according to Kalies. It costs roughly the same as a chain-link fence and holds up just as well structurally, based on her reports from developers.

“I love the idea of wildlife friendly fencing,” said Scott Starr, co-founder of Highline Renewables.

“You’re going to be a partner with the community for 30 plus years. So, you want to do things like screen it with evergreens or use wildlife friendly fencing […] and even if it’s a small upcharge, you are looking for things to make the project work that don’t just show up in the pro forma but are also a benefit to the community.”

As a developer who specializes in small-scale distributed generation, Starr notes that it’s common to screen for endangered species early on as part of choosing a site. “We are very careful as developers towards critical species, critical habitat, wetlands, things like that. That is part of the process.”

But, when it comes to sharing land with wildlife, the territory is more unfamiliar. Starr elaborates on the policy gaps in how governments incentivize wildlife-friendly buildout.

“The only things that I’ve really seen are ‘we’ll give you adders to put it on this rooftop!’ and ‘We’ll give you adders if you put it on a brownfield or co-locate with some kind of agricultural operations!’ said Starr. “There never is really anything about wildlife corridors—we just don’t know.”

While developers can’t claim that solar sites are equivalent to wildlife refuges, they do share some compelling similarities: they’re quiet, isolated, fenced off, and relatively low-disturbance on the landscape. Whether or not a site is wildlife-friendly often comes down to what’s adjacent to the facility, says Kalies, meaning rural sites typically have better luck than urban, overdeveloped, already-degraded plots of land.

Some of the biggest research-specific challenges for Kalies’s team include accessing sites in the first place, finding partners willing to collaborate, and hours of challenging fieldwork. Another difficulty lies in data interpretation. Even with data from camera traps, for example, seeing an animal onsite doesn’t mean it’s necessarily benefitting. The animal could be migrating, breeding or nesting, foraging, lost, or simply hanging out.

Starr adds that, from a developer’s perspective, even if you support wildlife-friendly fencing, you may get a ‘no’ from the county, from financiers, or from any long-term owners of the project who might consider wildlife a risk to their multi-million dollar asset. (Some developers are even concerned about bird droppings reducing the efficiency of their solar panels.)

Overall, the solar industry’s ability to become “wildlife-friendly” may depend on the level of discussion happening in government. “We need clear guidance and policymaking that incentivizes these kinds of considerations,” said Starr.

Despite these challenges, pursuing wildlife-friendly solar in North Carolina may be a promising step toward preserving biodiversity. The state ranks the 13th highest in the nation for risk of species loss. While wildlife movement patterns are being studied in the western U.S. (such as pronghorn migration), more research is needed on patterns in eastern states.

The first step to preserving biodiverse populations is ensuring that animals can continue to move freely across landscapes. Through siting adjustments, permeable fencing, planting wildflower pollinator habitat, and actively collaborating with scientists, the solar industry has a chance to protect wildlife. Energy developers and biologists alike can take part in this initiative, giving a new meaning to “energy conservation.”