Warming trend may intensify infectious diseases, scientists say

By Ester Wells

Global warming may make infectious diseases such as COVID-19 more widespread, warn health and climate experts. They say increasing temperatures are changing disease progression and interaction among people in ways that make it hard to predict and prepare for future public health crises.

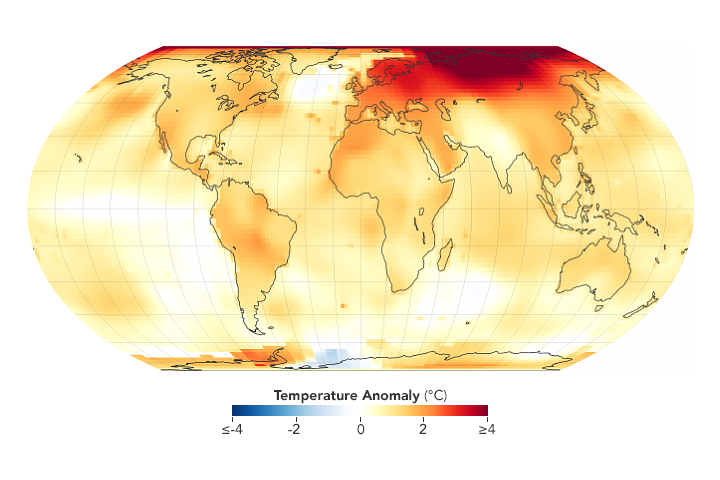

With 2020 tied with 2016 for the warmest year on record and COVID-19 topping 400,000 deaths in the U.S., climate change and public health are both at crisis points and inextricably linked. NASA scientists report that rising temperatures are part of the long-term trend of global warming, resulting in more droughts and heat waves, more intense and frequent hurricanes, and increased flooding and infrastructure damage.

“All of those things are being affected by the changes in climate, so the net effect of those is quite hard to predict ahead of time,” said Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, in a press webinar on 2020 temperature rise.

The warming climate is also affecting disease progression. Schmidt said diseases carried by hosts that are sensitive to temperature — mosquitoes, parasites or other organisms such as bats — will shift, making people more vulnerable to unknown diseases in the future.

These diseases may be spread more rapidly as people congregate in warmer weather. But colder weather is posing challenges as well. In the case of COVID-19, the winter season has made it likelier that people congregate indoors, where the virus is more easily transmitted to others.

“Coronaviruses are spread person to person, so the way that climate change is going to affect the spread of infectious diseases such as the COVID-19 virus is really how it changes the way people interact,” said Dr. Robert Horsburgh, professor of epidemiology at Boston University and founding steering committee chairman of the CDC’s Tuberculosis Epidemiologic Studies Consortium.

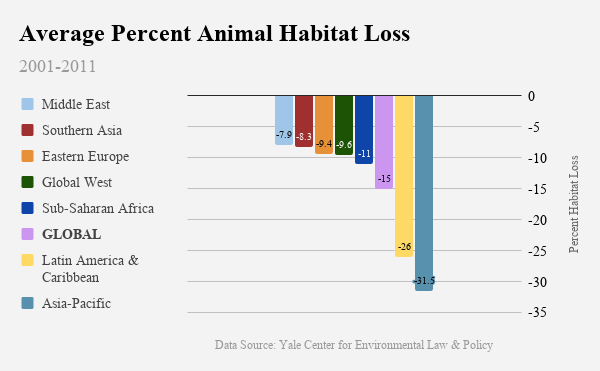

Horsburgh said deforestation and habitat destruction, accelerated by climate change, may expose more people to zoonotic diseases (those that pass from animals or insects to humans). Human expansion into natural areas increases interaction between people and pathogen-carrying animals.

At the same time, biodiversity loss poses challenges for antibiotic development to protect against new diseases. The World Wildlife Fund’s 2020 Living Planet Report found a nearly 70% decline in the population sizes of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish between 1970 and 2016. One in five plants are now threatened with extinction.

“We don’t know what we’ve missed,” he said. “Many of our effective biologicals come from plant sources … so there’s certainly a theoretical possibility that by changing the environment, we will lose some possible antibiotics in the future.”

Responding quickly is key. In his first few hours in office Wednesday, President Joe Biden signed a series of executive orders, including rejoining the Paris Agreement for international cooperation to curtail climate change and mandating mask-wearing on federal property. The day one directives promise more aggressive action by the Biden administration to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change.

But there is a lag in the effect human corrective activity will have on environmental recovery. The rollback of protective measures under former President Donald Trump, together with the delay of international negotiations due to COVID-19, will continue to have serious public health consequences.

“I’ve been saying for years that we’re not spending enough time to try to prevent the spread of infectious diseases, and perhaps the COVID epidemic has been a wake-up call,” Horsburgh said. “We need to be vigilant about looking out for the next epidemic — and it won’t be a coronavirus. It’ll be something that we never expected. That’s what’s hardest to prevent: something that you don’t expect.”