(Brian Yurasits/Unsplash https://unsplash.com/license)

(Brian Yurasits/Unsplash https://unsplash.com/license)

Last month, the state of Washington became the 8th state in the nation to implement a statewide ban on single-use plastic bags. Likewise, New York State celebrated the one year anniversary of it’s own plastic bag ban, which was instituted in October 2020.

More are likely to follow—and with good reason.

In the U.S. alone more than 100 billion plastic bags are used each year. These bags take centuries to degrade and remain toxic long after, polluting waterways, oceans and cities.

Still, there’s plenty of confusion and debate around plastic bans on both the political and practical level. It’s easy to get lost in the logistics of it all—but, at the heart of it, there’s one question:

Are bag laws effective?

Plastic bag bans are often regarded as a low-hanging fruit in the grand scheme of plastic waste. Everyone has seen plastic bags rolling across the street, caught in trees or floating in rivers. Given that it is such a visible form of pollution, it is an easy target for plastic policies; and this isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

As Mark Murray, executive director of Californians Against Waste, explained, it is exactly this visibility which makes banning bags a powerful symbol against plastic pollution.

“I’m not going to pretend that banning single-use plastic bags is going to be a major reduction in plastic pollution, but the fact that they are so visible is part of the reason to target them,” Murray said. “It’s easy for people to grasp that this is a wasteful product and it’s also pretty easy for people to see that there are alternatives.”

Another advantage is that implementing bag laws can serve as a gateway to other plastic policies down the road. The District of Columbia for instance, was a front-runner to the bag ban bandwagon, imposing a five-cent fee on all plastic and paper bags back in 2009. Since this law was passed, the Washington, D.C., government has been at the forefront of other plastic initiatives, becoming the second major U.S. city to ban single-use plastic straws in businesses and organizations selling or serving food or drinks.

Lillian Power, environmental protection specialist in District’s Department of Energy and Environment (DOEE), said that implementing these additional policies has been easier thanks to the initial bag tax.

“It really prepared a baseline as something to build off of, which has really helped us in our outreach campaigns for all these expanded regulations and requirements,” she said. “What it did was prepare these businesses for upcoming future changes and really realize that this is not the end of the line, it is just the beginning,”

Untangling the web

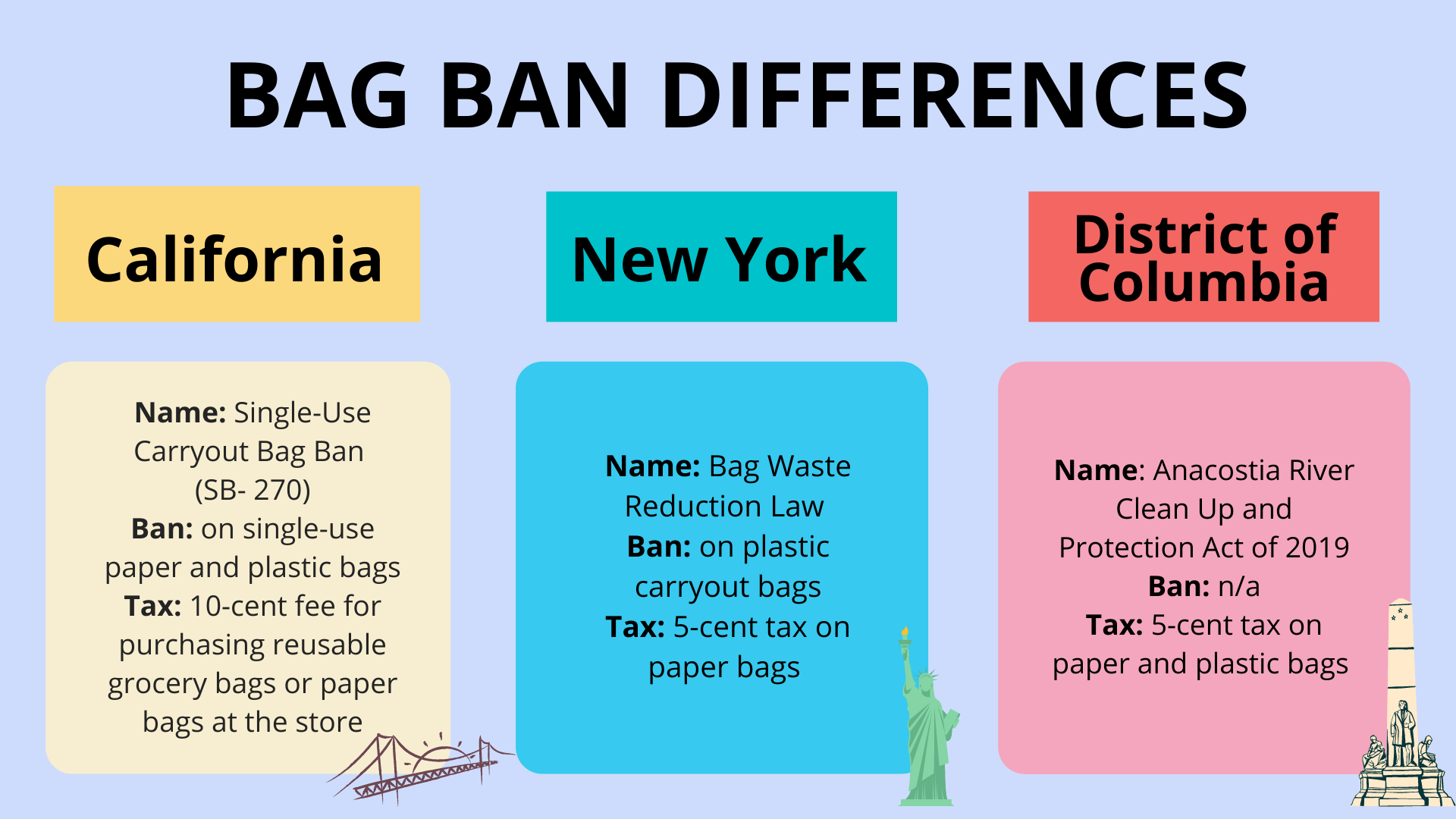

Keeping track of different bag bans and taxes can be confusing. As discussed, Washington, D.C., has a tax on both paper and plastic bags. In contrast, California passed a ban on single-use paper and plastic bags and began requiring stores to sell reusable grocery bags or recycled paper bags at a minimum of 10-cents per bag. Meanwhile, New York State has a ban on plastic bags and a five-cent fee on paper bags. Unlike Washington, D.C., the money does not go directly to the government and subsequent plastic clean-up programs. The five cent charge is a fee, not a tax, so the proceeds go directly to the businesses instead. All of these regulations can be even more varied on the local and municipal level.

The fact of the matter is that there isn’t a one-size fits all approach to bag laws. Each type has its own advantages and disadvantages––and having a variety of structures to choose from means states and cities can choose a method that best suits their needs.

An outright ban can be a sweeping change with a powerful message, but it can also be difficult to implement in the face of plastic bag lobbyists and manufacturers who may be inclined to sue. Enforcement also becomes an issue when a ban is implemented on a state-wide scale.

A tax, on the other hand, might seem like a half-measure—but it is actually extremely effective at changing consumer behavior by making customers more mindful about their bag usage. The money collected from the tax can also be used for plastic cleanup as illustrated in Washington, D.C., where revenue from the tax is put into a fund to clean up the local Anacostia river, as well as purchase and distribute reusable bags to low-income and eldery populations in the district.

Murray noted that ultimately both bans and taxes are successful at reducing plastic bag use because it causes the consumer to consider their own bag usage with every purchase.

“I think that having that charge upfront whether it’s in the form of a D.C. bag tax or in the form of having to buy a reusable bag … is causing people to reduce the number of bags that they generate,” he said. “Both you and the checker at the store are conscious of the fact that these aren’t freebies. There’s no such thing as a free bag, it was never a free bag.”

These assertions are backed by numerous studies. In California, a report by CalRecycle, a department within California’s Environmental Protection Agency, found that six months after the ban was implemented, 86% of customers brought their own reusable bag or opted for no bag. Consequently, there was an 85% reduction in the amount of plastic bags grocery stores provided to customers. Washington, D.C.’s 5-cent charge has led to a 60% drop in overall single-use bags and significant reduction in plastic bags found in the Anacostia river. Thanks to the tax, the bag law has generated more than $19 million in revenue to use toward cleanup and education efforts over the past decade.

Tips for Success

In the wake of bag law successes in places like California and Washington, D.C., many states and cities are eager to implement their own practices. However, gaining support for such a movement can be a daunting political challenge.

Tommy Wells, director of D.C.’s Department of Energy and Environment and the creator of Washington, D.C.’s bag tax shared his advice on making people more accepting of bag laws.

Wells explained that when he was first considering implementing the tax, businesses feared customers would become angry with them and assume the tax was another way to make money. As a result, Wells implemented an extensive educational campaign to ensure people knew the tax was the government’s doing.

“We put ‘Skip the Bag, Save the River’ stickers all over the bus and stores and we made it clear to everyone that the government was doing this,” he said. “People just get it now. It’s part of living here. Some people will still grumble but there’s not enough out there for any politicians to say they would repeal it.”

Powers added, “It does require really deliberate action on getting the word out … (The stickers) are one of those eloquently simple solutions where the cashiers are just pointing to the stickers and saying ‘call the DOEE, it’s not our fault.’”

The statistics back this claim with a survey commissioned by the DOEE showing 83% of DC residents and 90% of D.C. businesses support the bag law or are neutral towards it.

Looking back at his work advocating for the legislation of California’s single-use bag ban, Murray recommended gaining support and implementing laws on a local level. California was the first state with a uniform state-wide plastic bag reduction law, but that all began with cities like San Jose and San Francisco first implementing their own local laws to significant success. San Francisco, in fact, was the first major US city to ban single-use plastics.

In terms of tangible steps, Murray suggested reaching out to a local recycling coordinator, who can be an ally and resource for further political action.

“Every community typically has a local recycling coordinator or a staff person for the city or county that works on these issues, whose task is to reduce waste and increase recycling,” he said. “Not only can they help in terms of giving you a little bit of history, like if anyone tried this before, but they can also tell you who are the champions on the city council or on the board of supervisors…”

Murray said Californians Against Waste employed this exact technique during their efforts to pass the single-use carryout bag ban. Now as the organization looks to expand the scope of the ban––extending the policy beyond single-use plastics and beyond non-food retailers––they have continued efforts at the local level and remained in contact with recycling coordinators.

The future of plastic

When it comes to continued action after plastic bag bans, there are many routes to choose from. As Californians Against Waste has demonstrated, one option is to expand upon bag law requirements, such as petitioning for a plastic ban beyond just single-use. Another option is to ban other types of plastic, like Washington, D.C., did with single-use straws.

However, an increasingly important focus in the bag ban debate is the idea of “Extended Producer Responsibility,” or EPR for short. While most of the existing bag laws seek to change existing consumer behavior, EPR legislation seeks to stop plastic waste at its source by taxing the producers of the plastic bags in the first place.

While this is certainly harder to implement in the face of huge plastic bag companies and lobbyists, this type of taxation requires plastic manufacturers to take responsibility for their actions, meaning at the end of the day, the polluter is the one that pays.

As Jackie Nuñez, program advocacy manager for the Plastic Pollution Coalition, explained, advocating for this type of legislation is necessary because big companies will not reduce waste by their own accord.

“There is a place for it because historically time and again businesses won’t self-regulate themselves,” she said. “They need those parameters, you need those boundaries … The people who make this stuff should be responsible for it in life.”

While the task may seem intimidating, Powers insisted this could be done from the local side.

“You just need to get resident support and you gotta pass the laws,” she said. “You’re not going to get these behemoths of industry to make these changes on a closed time scale unless they are 100% forced to.”

This is easier said than done, but EPR laws are gaining traction in the U.S. In July of this year, Maine became the first state in the U.S. to pass an EPR packaging law requiring big corporations and manufactures to pay for a portion of the recycling costs of the packaging material (typically plastic) that they put into the market. Oregon followed suit with a similar law in August.

It hasn’t been so easy in California, where Murray said Californians Against Waste has been trying to implement EPR laws for years, with little success. He added that while EPR might be the right policy to implement, it’s not necessarily the easiest.

“Sometimes the ban is the easier policy for policy makers in the public to wrap their arms around and understand,” he said. “We don’t always get to do the best thing when we’re advocating these policies.”

Despite the hurdles, Murray remains optimistic as more people become open to bag laws.

“At the beginning … we would pass one or two of these policies every few years and now policymakers are really seeking us out and seeking out these policies,” he said. “Really, for the first time we talk about circular economy and producer responsibility and they know what we’re talking about … I feel like policymakers are getting it.”

––

Editor’s Note: This story is part of the Planet Forward series “So Long, Single-Use?” Check back over the next several weeks for more stories about how communities and individuals can––and are––reducing single-use plastic waste.