Sandcastles and the seawall

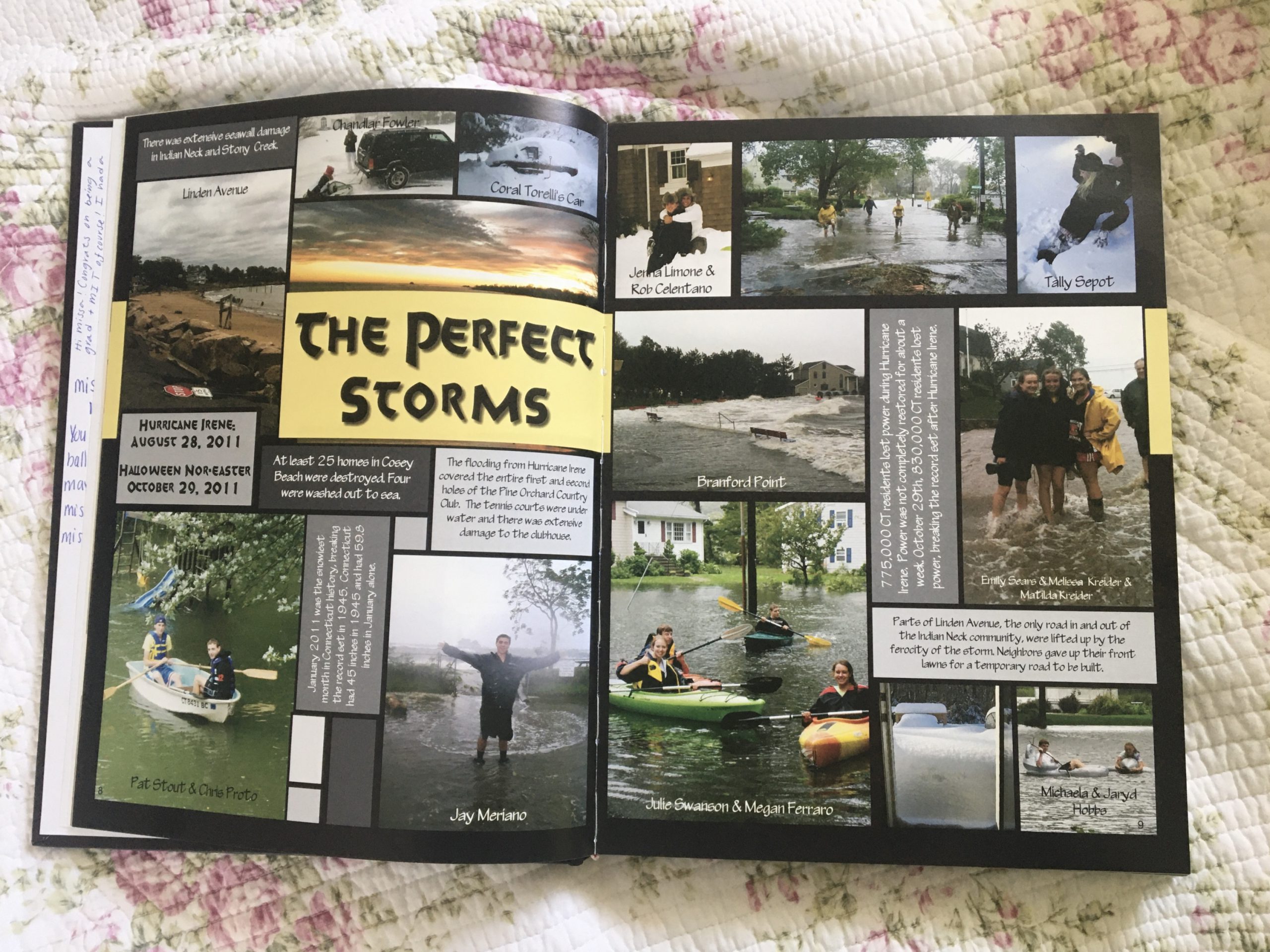

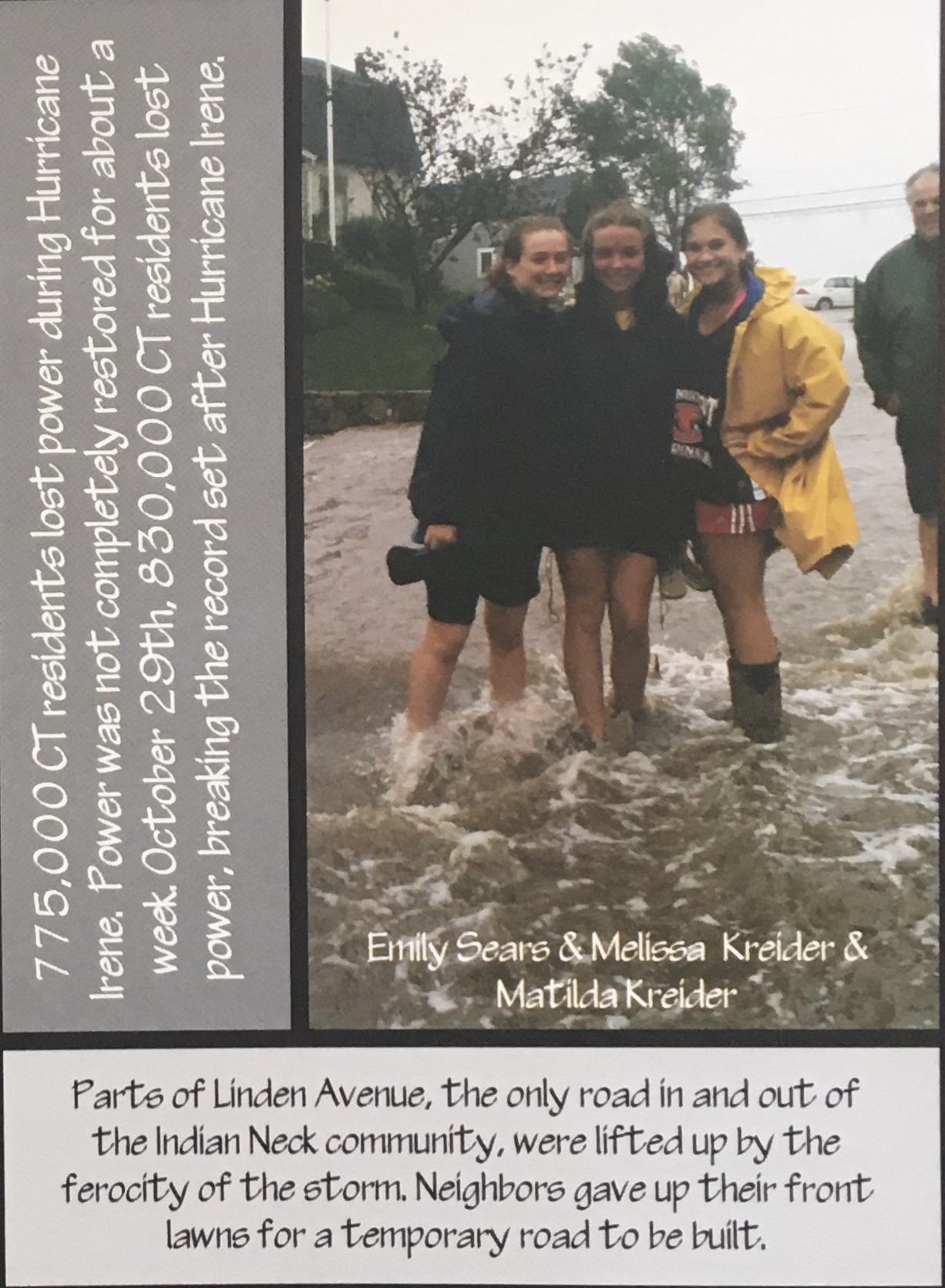

I never viewed the sea as a destructive force until Hurricane Irene hit my hometown of Branford, Connecticut, when I was 13. Like the reckless people you see on a newscast, my family didn’t evacuate because we had no idea what to expect.

We watched waves pour over our front yard, our mailbox looking like it had been mistakenly plopped down in the middle of the ocean. Waves hit the windows on our second-floor deck, water rushed past our windows, and I began to wonder if we might float away, too.

When the storm had mostly passed, the neighborhood began to come out of hiding to check on each other and fulfill our curious natures. The massive Jersey barriers – made of concrete and bolted down with steel – had been pushed across the street onto our lawns. Our backyard was covered in inches of sand, and there were starfish lying prone in the driveway. The ocean we all loved so dearly came closer than ever before to pay us a visit, and maybe to give us a warning.

The following year we evacuated for Hurricane Sandy and returned the following day to find that the sand beneath the state road had been washed away, leaving the road suspended in the air. The granite blocks in front of our house had dropped into the ground as it opened up, and I remember staring at the hole where my front yard used to be and feeling that we were in over our heads in more ways than one.

For me, growing up in a beach house in a town that comes alive in the summer was paradise. But it will soon be paradise submerged.

The Seawall

At a neighborhood meeting in May 2018, I lingered at the back of the room, letting my parents and their neighbors contend with the reality of their disappearing property. Familiar faces leaned over the map held by a state civil engineer who seemed too young to be in charge of saving a neighborhood.

The state of Connecticut is building a $5.8 million seawall on the state road that stands between the Long Island Sound and my neighborhood, which consists mostly of old beach cottages set back less than 50 feet from the place where land gives way to water. The state is aiming not to protect houses but to protect Route 146, since it was severely undermined when Hurricane Sandy washed the land out from beneath it.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers estimates the Long Island Sound will rise 6.24 inches higher in the next 15 years; the road is only three feet above the current high tide mark, so it’s no wonder the state is starting to worry.

The people who built my house and others like it in the 1920s looked at an undeveloped beach and saw only opportunity. Then the deadly Hurricane of 1938 and countless other hurricanes and Nor’easters hit the town with growing intensity, but beachfront houses continued to pop up on my street like elaborate sandcastles just waiting for the tide to come. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the desire for beachfront property remains constant even as the beachfront creeps ever closer.

We severely underestimate the power of the ocean, just as we underestimate the impacts of a changing climate. Whether the year is 2018 or 2033, a Category 3 hurricane like Hurricane Katrina or Hurricane Irma would flood my family’s entire property with a layer of 11 feet of water, while another category 1 storm like Hurricane Sandy would dump five feet of water on us. Nor’easters and hurricanes become more extreme as they’re fueled by increasing ocean temperatures and they reach further onshore due to sea-level rise, meaning we can expect more starfish in the driveway every year.

Climate change and the resultant sea-level rise is the most significant reason we need a seawall, but rarely was the phrase “climate change” uttered at that neighborhood meeting. There’s a major cognitive distance between sea-level rise as an abstract concept and a sea-level that could reach our driveways in less than a century.

But in 2019, the town of Branford did something amazing — something that surprised me. The town invested $1 million in a new coastal resiliency fund as a way to save for the future climate costs like repairing washed-out roads and bridges. Quietly, without any fanfare, Branford made a commitment to its future and acknowledged the threat of climate change in a major way.

The Sandcastles

I have this apocalyptic vision in my head of fish swimming by the stop sign where I once waited for the bus, of my childhood bed floating through sunlit water long after my parents have fled for higher ground. There’s no violent destruction or fear in my vision because I’ve grown up with this reality. Maybe the next hurricane will knock the house down, but in my head, my childhood home stays in the same place as the ocean overtakes it, a symbolic reminder that the land was never ours to begin with, and that humans have majorly screwed up.

In some ways, I believe my drive to become an environmental journalist stems from my life experiences of reckoning with the rising sea. It’s hard to grow up with hurricanes as a character in your life story and not develop a curiosity about the climate. I’m not trying to save myself – seawall or not, I believe it may be too late for my neighborhood – but I want to help turn our trajectory around for other people, if I can, or at least help people adjust to the new world we’ll be living in.

I’m most concerned about people who are far less privileged than I am: people who live in places like the Bahamas or Puerto Rico and have no way to escape the fury of a hurricane. People who have played little to no role in carbon emissions still must watch the sea approach them, suffering the crash of a wave that began on shores far away.

While I may one day lose my house and my neighborhood, other people will lose their jobs, families, and lives. Entire countries will be wiped off the map. Every island you’ve ever vacationed on could be just decades away from being a memory that geographers point to, identifying the spot where land and lives used to be. Not all sea-level rise is equal in effect, and compared to other people in the world, my story is far from a tragedy.

People like my family and neighbors got lucky, living in the middle of a New England beach postcard, and then because of the choices we made, our luck ran out. But maybe we can prolong the daydream for a little longer…

And so we’re building a seawall, which will hold off the storms and seas for some time. But if there’s anything I’ve learned from playing in the sand, it’s that human constructions are trivial compared to the power of the ocean. We’ve seen that with the destruction of levees in New Orleans, piers in New Jersey, and entire towns in the Bahamas. There is plenty we can do to become more resilient in the meantime, like building seawalls and lifting homes onto stilts, but the reality for places like Branford is that people will one day have to move away.

High on a cliff over the Branford River, there’s a big, sandy-colored mansion complete with turrets and crenellations that we jokingly refer to as “the sandcastle.” But the irony is that that house will survive far longer than the houses on my street. The real sandcastles are houses like mine; hastily constructed too close to the sea with the optimism of a child building sandcastles and believing they’ll be there forever. I long for the days when I, too, thought that the rising sea would never reach me.