Shannon Beirne and Abigail Foerstner

Shannon Beirne and Abigail Foerstner

By Shannon Beirne

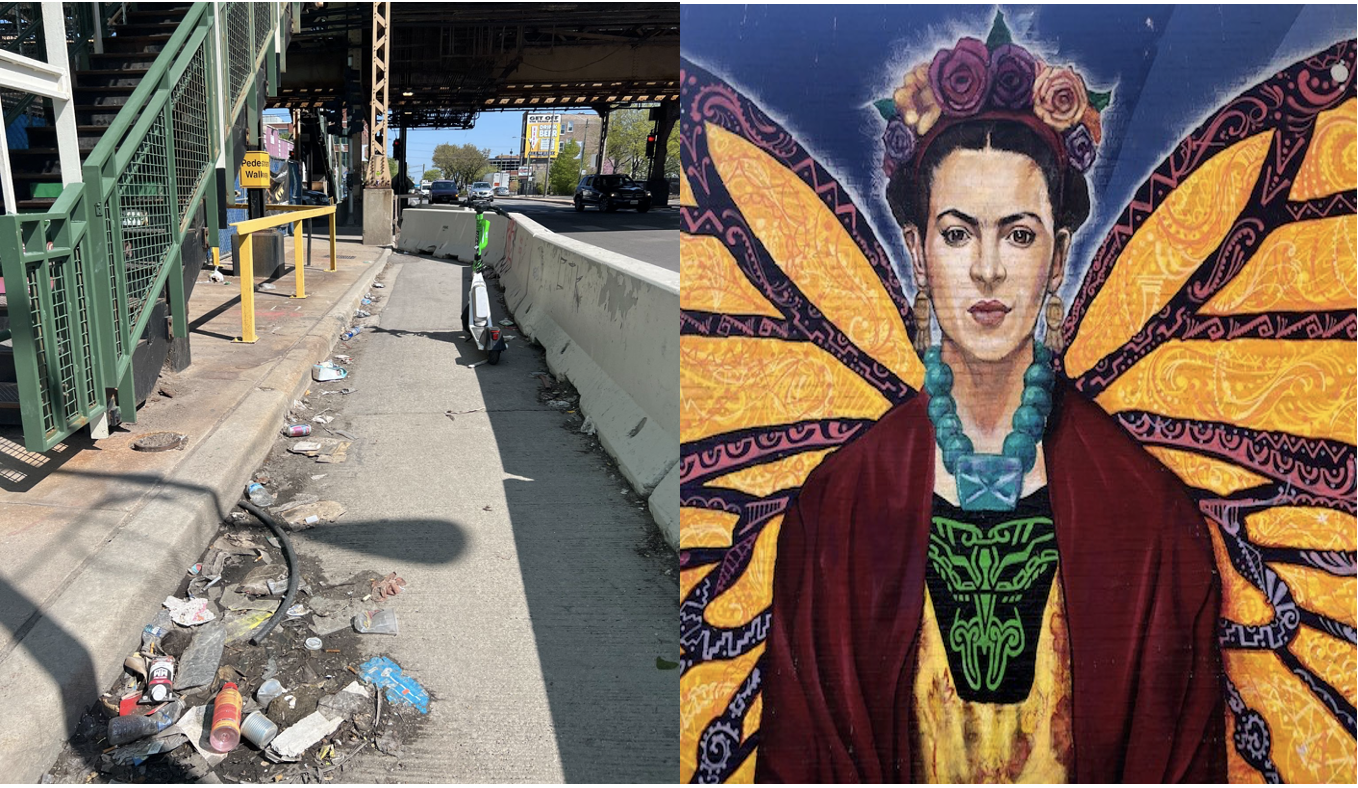

As children ride their bikes home from school, play soccer in Carter Park and walk to nearby shops to enjoy their favorite treats, they breathe in air from one of the most polluted neighborhoods in Chicago.

The airborne pollutants from truck traffic and industry pervade homes, schools and streets, casting a shadow over the health and well-being of Pilsen’s residents, local environmentalists point out. They back up their claims with city, state EPA and their own measurements.

Located in an industrial corridor, Pilsen faces high levels of air, soil and water pollution all exacerbated by daily emissions from cars, buses and trucks that insidiously infiltrate the vulnerable lungs of residents, especially those of children, according to Gloria Barrera, member of the Illinois Association of School Nurses. The neighborhood has a high level of childhood asthma.

In Little Village, the neighborhood west of Pilsen, 1,661 heavy-duty trucks whirred through the intersection at 36th Street and Pulaski Avenue in the span of 24 hours. Neighbors for Environmental Justice (N4EJ) collected the figures at this and other intersections in industrial corridors.

N4EJ, an organization dedicated to promoting community action on environmental justice and achieving environmental health, works alongside groups such as Pilsen Neighbors Community Council in the fight to protect the neighborhood from an expanding industrial corridor. The corridors are disproportionately located in communities of color.

A concern associated with the expansion of the industrial corridors focuses on health concerns. Residents who live in these industrial corridors are exposed to high levels of air pollution known as particulate matter – chemicals and contaminants that can embed deeply in the lungs and cause serious health problems.

The Pilsen Neighbors Community Council organized a virtual panel discussion on May 24, to discuss the consequences of environmental pollution in the Pilsen community on children’s health.

Chris Martinez, CEO of the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, explained that nine counties in Illinois, including Cook County where Chicago is located, rank in the top 9% nationwide for diesel engine pollution. Cook is even in the top 1%. Last year, Cook County reported 2,251 asthma attacks, 66 asthma emergency department visits and 4,167 respiratory illness cases, according to Martinez. In comparison, Iroquois County, at the bottom of the list for diesel engine pollution, reported seven asthma attacks, zero asthma emergency department visits and 12 respiratory illness cases, according to Martinez.

Mappings from the Chicago Department of Public Health show Pilsen to be among the most heavily polluted communities in Chicago.

Devin Cooley, a volunteer from Neighbors for an Equitable Transition to Zero-Emission, explained that approximately 800,000 people in Illinois have asthma and roughly 300,000 are children. According to Cooley, there were 72,810 emergency visits with the primary diagnosis of asthma last year.

“I feel a deep sadness because of course we should have a right to breathing clean air. Especially our children have a right to breathing clean air,” said Karin Stein, a panel leader from Moms Clean Air Force.

When considering air quality, the main criteria pollutants scientists look at are particulate matter ozone, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and lead, according to Northwestern University Earth and planetary sciences Ph.D. candidate, Anastasia Montgomery.

“The problem is that particles from air pollution rest on top of your lungs and lead to health conditions like lung disease,” Montgomery said.

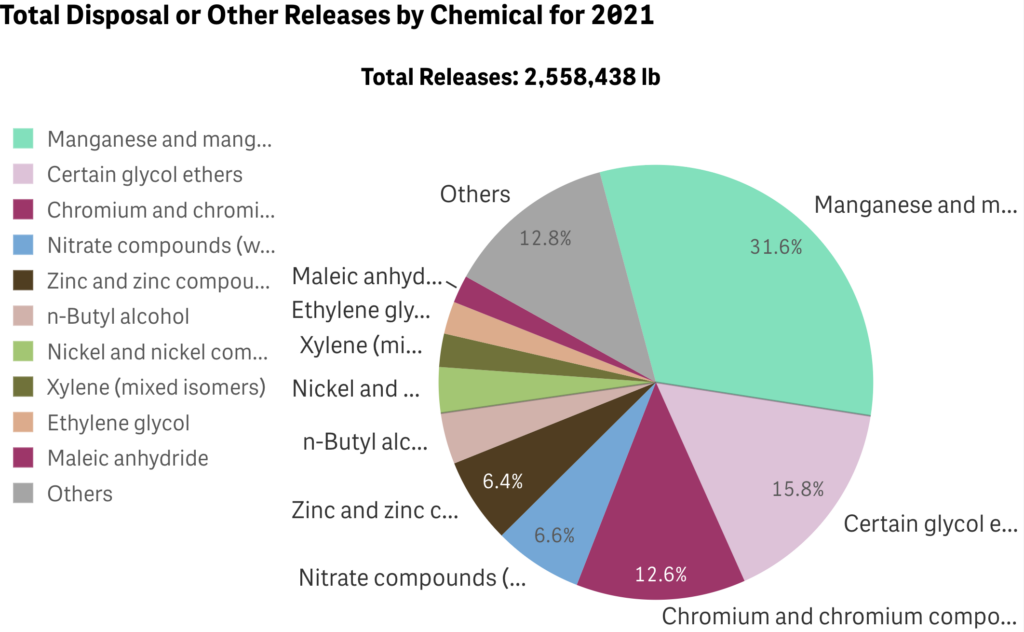

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Toxic Release Inventory, manganese and manganese compounds account for 31.6% of chemical releases in Pilsen, namely from diesel vehicle emissions. Manganese is an essential nutrient vital to staying healthy. However, in excess amounts, it can be neurotoxic (harmful to the brain). Potential health effects include trembling, stiffness, slow motor movement and even severe depression and anxiety.

Another chemical reported at nearly 16% of total releases is n-Butyl alcohol. Butyl alcohols are widely used industrial solvents. They are common in pesticide products and found in agricultural practices. N-Butyl alcohol can cause redness and tearing of the eyes, scratchy throat, itching and redness of skin and headache.

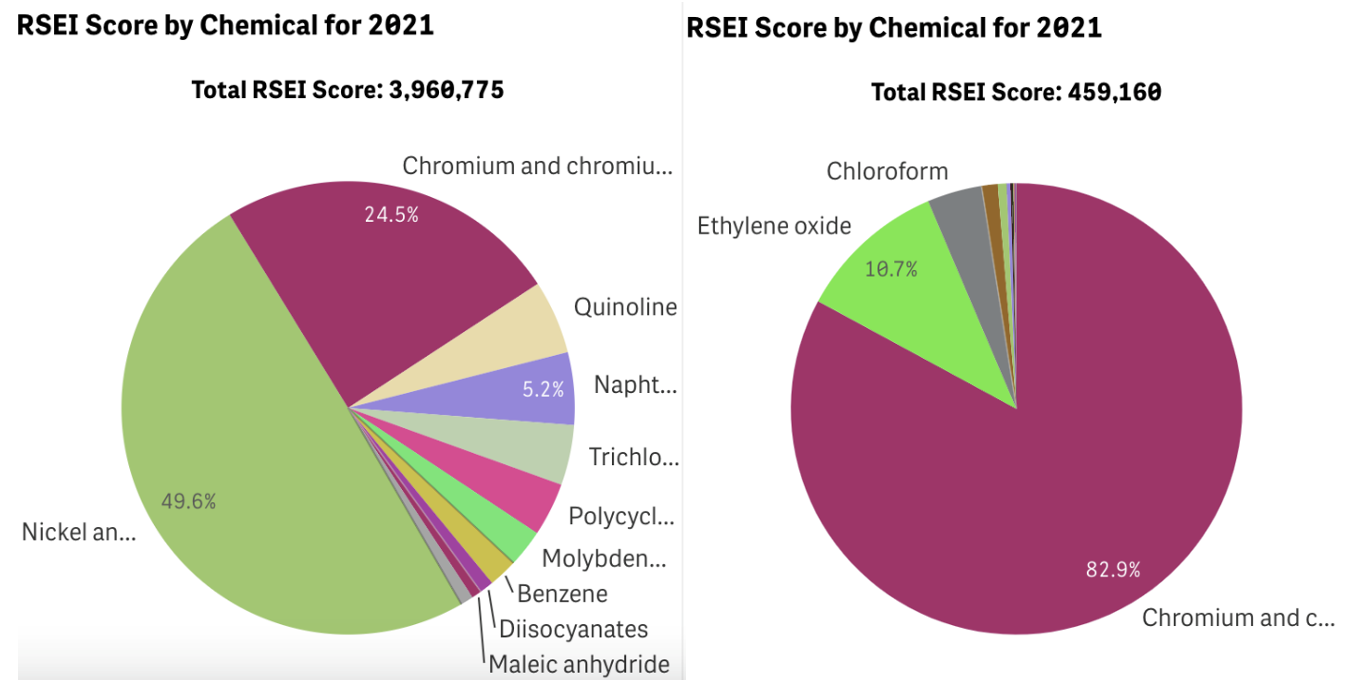

In the EPA’s 2021 Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators (RSEI) score, which weighs toxicity of elements, health impacts, nearby populations and quantity, among other factors, Pilsen scored 3,960,775, a relative figure for comparison to other neighborhoods. Neighborhoods on the North Side of Chicago scored severely less, one coming in at 459,160.

Air quality is “actually the leading cause of death globally,” according to Montgomery. “Approximately one hundred thousand people per year experience premature mortality because of exposure to air pollutants,” continued Montgomery.

Children tend to be especially vulnerable to air pollution because their lungs are growing and tend to spend more time outdoors, according to the American Lung Association.

This is one of the reasons why environmental activists such as Alfredo Romo, the executive director of N4EJ, are upset that MAT Asphalt moved into McKinley Park less than 1,000 feet from schools and parks.

“The proximity of heavy industry next door to a park, it’s just ridiculous,” Romo said. “Next door to schools, it’s just very troubling,” continued Romo.

MAT Asphalt, an asphalt mixing plant located in McKinley Park near Pilsen, has faced many pollution complaints in these neighborhoods. In a meeting with Joe Haughey, one of the owners of MAT Asphalt, he addressed some of the public’s concerns and changes MAT Asphalt is making in response to complaints and citations.

Haughey explained that asphalt mixing plants have a small radius in which they can work because the paving mixture cools down quickly. The mixture comes out of the tank at over 300°F, and to keep the temperature high, trucks ideally travel less than 30 minutes to their destination, one hour being the max.

“I would love to move out to the middle of nowhere,” Haughey said. “But that’s just not how it works.”

Haughey said he understands that the community was upset when MAT Asphalt moved in unannounced. However, he cites the importance of available infrastructure for construction in cities and for the safety of company drivers.

Haughey, emphasizing his commitment as an environmentalist, aims to minimize emissions and implement safe practices. Last year, an environmental analysis conducted by a consultant for MAT Asphalt revealed that its air pollution levels remained well below state limits, as stated by Haughey.

To further reduce emissions, Haughey said the company plans to reconstruct the current system for transferring hot asphalt into trucks. By this October, MAT Asphalt will have a garage built around the storage unit. That way, when dump trucks collect hot asphalt, any emissions from the process will be trapped in the enclosed space. The pollution will be condensed, and an environmental organization will collect and dispose of the remnants, he said.

Still, community members continue to be upset that the industrial corridor in Pilsen and its surrounding neighborhoods is growing.

Mary Gonzales, a long-time member of Pilsen Neighbors Community Council, lay leader at St Paul’s Catholic Church, and avid environmental activist, cites the pollution in the area’s industrial corridor as being responsible for high rates of asthma and lung disease within the community.

“I myself have lung disease, and I don’t smoke. But I have lung disease because I live in this neighborhood. My mother died of lung disease because she lived in this neighborhood,” said Gonzales. “More children carry asthma pumps in this neighborhood than anywhere else in the city. Maybe anywhere else in the country,” continued Gonzales.

There are reasons to bring industry into the city, noted Montgomery.

“It’s important to have that kind of employment and making sure that there’s opportunities for people who may not have white collar jobs,” Montgomery said. “With that being said, there are standards that we should uphold. We need to make sure that industrial facilities trap the pollution at the source and don’t make it the neighborhood’s problem,” continued Montgomery.

Based on Haughey’s comments, MAT Asphalt’s new directive will attempt to address what Montgomery calls for. But Pilsen residents continue to remain steadfast. N4EJ, the Pilsen Neighbors Community Council and others are among a few organizations that hope to pave way for a clean future for all children in the city.