Astry Rodriguez

Astry Rodriguez

Some of the planet’s biggest challenges are those that need multiple solutions, addressing the problem from every angle.

Climate change brings about fluctuations in temperature, precipitation patterns and extreme weather events, which disrupt and reduce agricultural productivity. Increasing biodiversity and plant precision breeding are techniques that can create agricultural resistance to climate change.

Precision breeding can help agriculture get ahead of climate change effects such as drought and strong storms by making plants resistant to them, according to Ryan Mertz, operations lead at the Bayer Marana Product Development Center in southern Arizona.

Reduced food availability is a big concern due to climate change, according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency. Climate change has caused increased severity of droughts and floods that cause challenges in raising crops. Crop yields are particularly important in the U.S. as the national sector supplies nearly 25% of all grains on the global market.

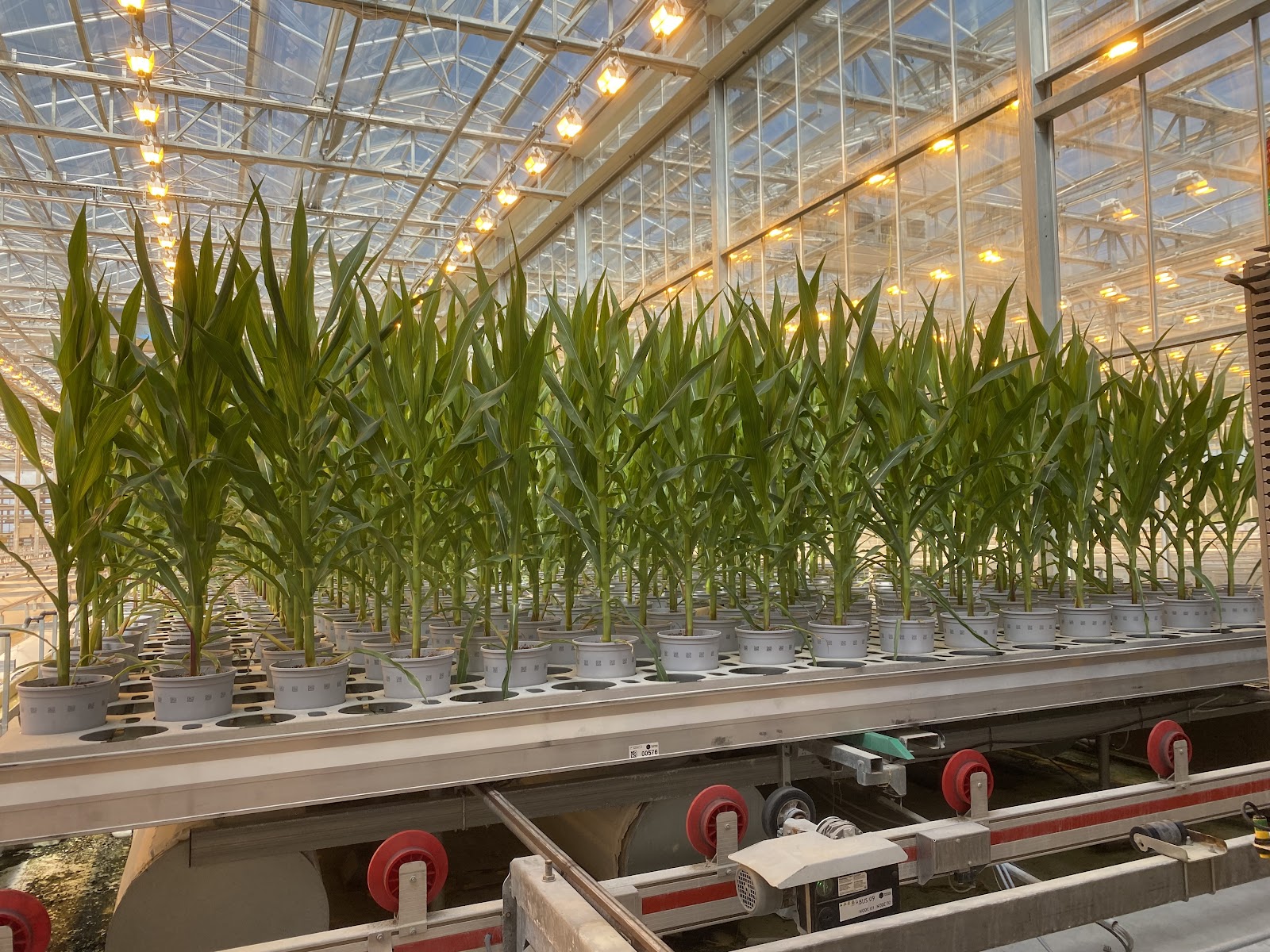

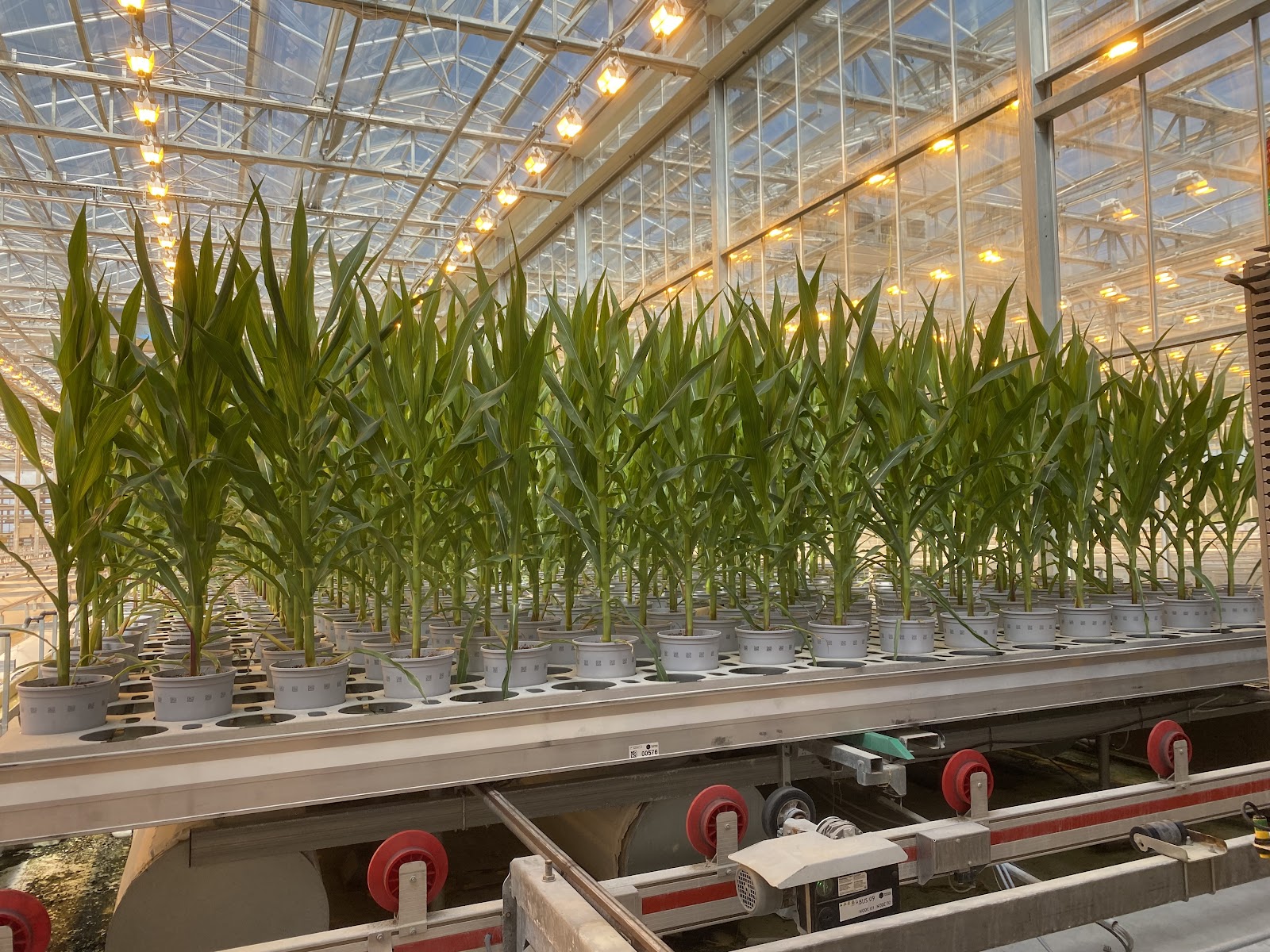

Bayer, which operates a climate-regulated greenhouse outside of Tucson, Arizona, is using plant breeding to develop new products for farmers globally.

Scientists use DNA analysis to see the traits in the corn seeds, designing products by analyzing billions of genomic data points over time. At the Bayer facility, there are automatic seeders that follow the identities of each seed and place them into germination trays until they sprout seven to 10 days later. If the seedlings’ size and vigor look promising, they are ready to be planted.

The Bayer site in Arizona is centering its attention on short-stature corn, which is sturdier due to its low height and more resistant to strong winds.

“We’re always trying to innovate. [With] climate change, you’ll have bigger storms, extreme floods, or drought conditions,” Mertz said. “Bayer is working to constantly improve their products.”

Plant breeding can lead to new crops and also contribute to plant biodiversity, which is significant as new varieties of plants can be made to adapt to environmental stress conditions — meaning less food loss in fields — and create diversity that maintains functions of an agroecosystem. Biodiversity has also been achieved differently through Native techniques.

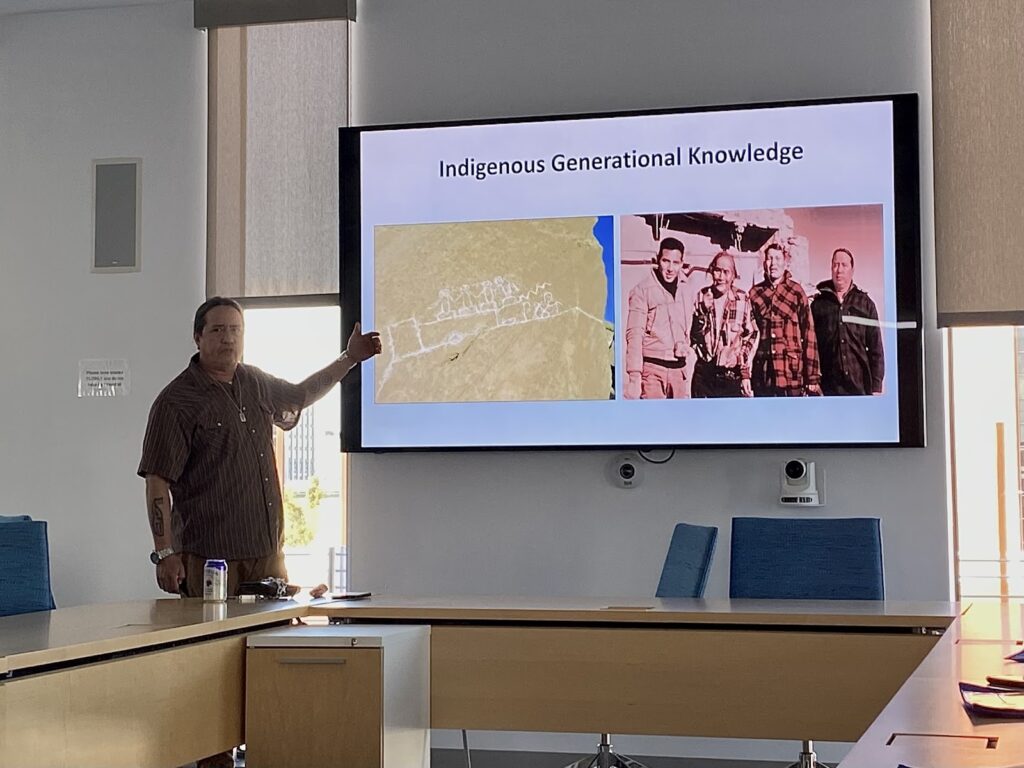

Genetic biodiversity is the key to climate adaptation, according to Michael Kotutwa Johnson, Ph.D., assistant specialist at the University of Arizona School of Natural Resources and the Environment and member of the Hopi Tribe in Northern Arizona.

Plant biodiversity entails having crops that are physically different. For example, Hopi corn varieties are not all the same height, produce varying numbers of ears, and are different colors, Johnson said. To achieve this diversity, people must plant crops year in and year out.

Johnson said he was able to eat corn that was 30-40 years old, that was dried out and preserved, by boiling it in water and making it “come back to life.”

“That’s what food security is. Making sure that our future generations can have this, and this food right now is nutrient-dense,” Johnson said. “Those seeds are like us, they represent us. So if you take care of them, nurture them, they come back to life.”

Indigenous value systems allow for them to have a large biodiversity, because they have a relationship with the environment that is not based on gross domestic products, Johnson said.

Indigenous lands contain 80% of the world’s biodiversity, while Indigenous peoples make up only 5% of the world’s population. Many of these communities demonstrate that having small farms or gardens is not an obstacle to achieving plant biodiversity.

On his roughly 11-acre farm, Johnson grows corn, squash, melons, peach trees and other food varieties.

This year, Johnson lost some crops to heat stress, but the ones that produced seeds he will save and plant in a year or more depending on heat conditions, he said. According to Johnson, this has been practiced by Hopi for well over 2,000 years. He said his people have been planting for so long that they have produced genetically diverse plants with different rooting systems, ones that are deep or shallow. Both are necessary for optimizing nutrient capture from different soil types.

Johnson said that technology such as automatic planters and tools to healthfully remove topsoil can be helpful in agriculture, but when it comes to achieving genetic biodiversity, the Hopi have all the traditional tools they need. While scaling this biodiversity may not be possible due to the manual labor needs involved, the practices that cultivate such biodiversity are sacred food ways that every person is dependent on, Johnson said.

“As a result of planting every year, plants such as corn — which originated in South America over 10,000 years ago with fairly high rates of precipitation (30 inches or more) — are able to thrive in our climate, which only produces six to 10 inches of annual precipitation,” Johnson said.

According to Johnson, this is thanks, in part, to the process of starting small before scaling even becomes an option. “A lot of the technology can be very useful. We’re always talking about upscaling, but I think it’s almost better to create a system ahead of the scale because some stuff is just unscalable.”