Labor activists join environmentalists wearing turtle costumes at the 1999 WTO protests in Seattle, Washington. (Courtesy of the Seattle Municipal Archives, Item 175623)

Labor activists join environmentalists wearing turtle costumes at the 1999 WTO protests in Seattle, Washington. (Courtesy of the Seattle Municipal Archives, Item 175623)

We know we’re dumping carbon in the atmosphere,

It’s warming the earth, messin’ with the oceans, climate change is here.

We know what we’ve got to do, leave it in the ground;

Look to the sun, feel the wind, listen to the sound.

Long sung from the throats of Ralph Chaplin, Pete Seager, and workers around the world, “Solidarity forever / For the union makes us strong!” is the authentic fighting song for organized labor, centering solidarity as their greatest strength against exploitative capital. Yet for Joe Uehlein, it is hard not to see this as a “hollow slogan” after more than four decades at the intersection of labor organizing and environmental activism. To him, the climate crisis has pulled organized labor’s priorities—its “two hearts beating within a single breast”—in opposite directions, giving into a false duality of “jobs vs. environment” as though we can’t have one without the other.

As one heart fights for the health, safety, and future of its members, the other must protect their jobs, as “the smoke coming out of the steel mill smokestacks… [means] bread on the table” for America’s working class. Through his tireless work as a union organizer, environmentalist, and musician, Uehlein picks out a new tune that “speaks to something other than the intellect,” helping those beating hearts “recognize each other” and coalesce environmentalism with organized labor, taking down the barriers that keep these movements in separate “silos” to fight for a just, sustainable future.

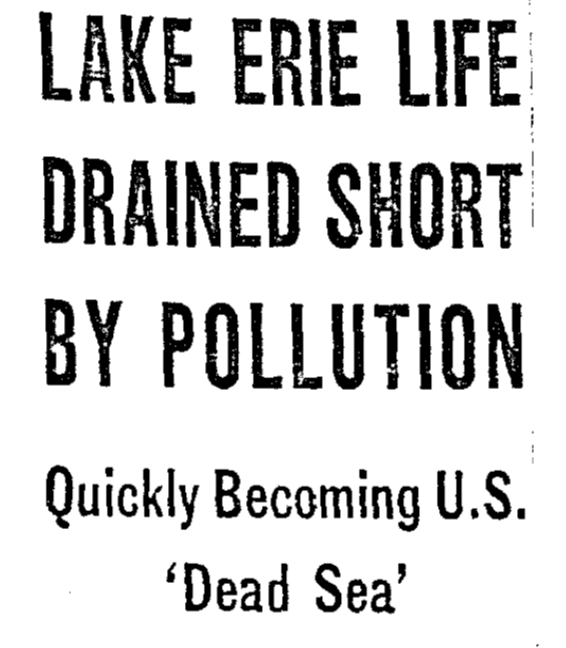

Though they normally occupy two separate political spheres, organized labor and environmental activism could not be more relevant, more interlinked, or more personal for Uehlein. The social life of his Ohio hometown revolved around the United Steelworkers Local 1104 union hall, and both of his parents made ends meet thanks to their union work. But when the nearby Cuyahoga River caught fire, Uehlein and his community were forced to question what they were doing to “[their] paradise, Lake Erie.” Signs reading “Don’t Swim in the Lake” and “Don’t Eat the Perch” were visceral reminders that the steel mill’s smokestacks represented more than just their daily bread.

Uehlein brought this environmental consideration to the forefront of his work. After his early career in several union jobs—both as a manufacturing and construction worker, and as a union rep—and election to Secretary-Treasurer for the industrial division of the AFL-CIO—the nation’s largest federation of unions—he joined the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 1988. “I’d never heard of global warming,” Uehlein said, “but I read about the [congressional] testimony…and I thought, I’m representing the energy unions, mine workers, steelworkers, refinery workers. I better learn about this.” Seeing both the available science and the presence of foreign labor unions, Uehlein judged that America’s labor movement was dangerously unconcerned with the looming danger of climate change. However, pushed by the energy unions under their banner, the AFL-CIO opposed Uehlein’s work on the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, undercutting their own representation on the Panel and causing Uehlein to resign in frustration.

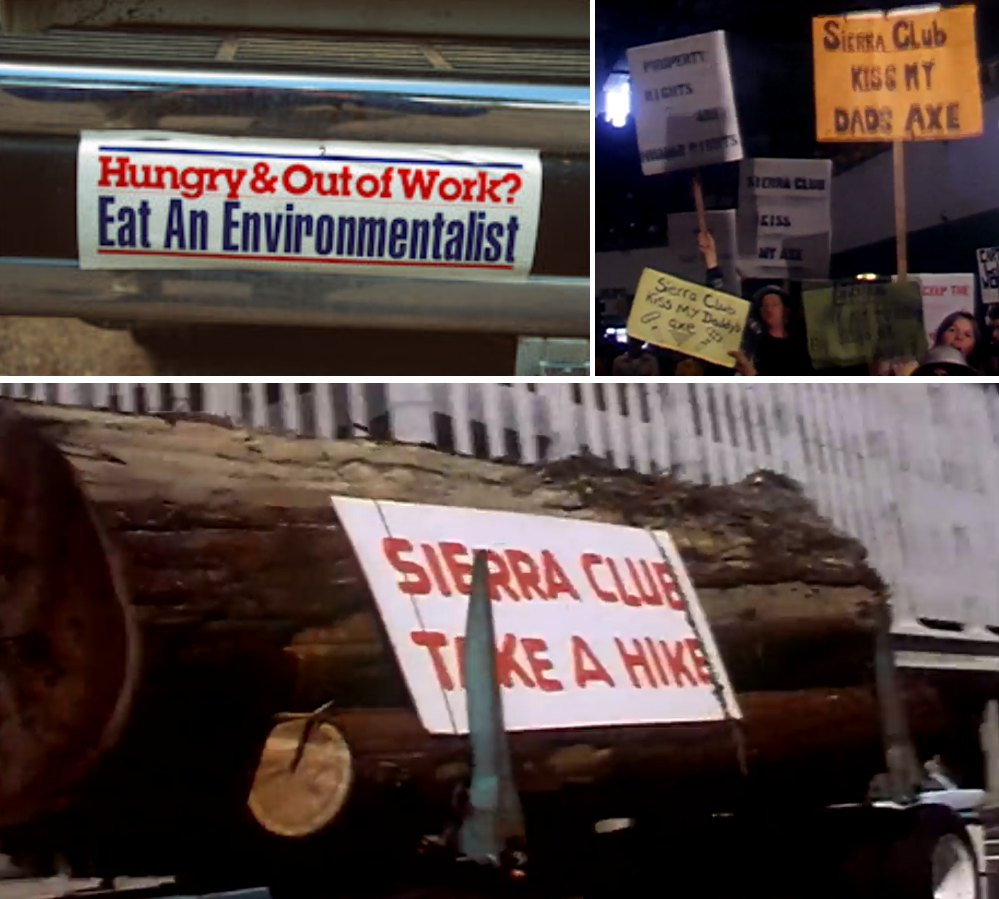

Why is the AFL-CIO so reticent in its attitude on climate, despite the danger to its roughly 12.5 million members and to working people around the globe? Of its 57 affiliated unions, many have no stated environmental policy, while a handful advocate for some climate action as a peripheral issue. That leaves a bloc of about a dozen unions—the building trades, steel, utility, and mine workers whose jobs depend on the fossil fuel industry or other climate-unsustainable sectors. Far from being outright malicious, these unions have a legal duty to advocate for their members, especially in a time of increasing wealth inequality and corporate power. Thus, these powerful and highly motivated energy unions direct the entire AFL-CIO into an “All of the Above” energy policy, accepting “green jobs” and infrastructure projects while vehemently opposing any attempts to curtail extractive industries. In the early 1980s, pressure from the United Mine Workers dissolved the AFL-CIO’s action on community health issues like air pollution and acid rain, and toxic rhetoric about “jobs vs. environment” has continued to poison labor’s political action. Following protests against the Keystone XL pipeline, special interests like the American Petroleum Institute have learned to inflame these tensions and now wield huge influence through energy unions.

According to Uehlein, correcting this is a matter of advocacy. Yet, in his experience as a strategic advisor for the Blue-Green Alliance, a founding member of the Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies, a member of the Union of Concerned Scientists, the chief organizer of the AFL-CIO’s 50,000-strong presence at the 1999 WTO protests, and leading countless workshops on cross-issue activism, Uehlein observes that the prominent environmental groups who ought to be leading this charge are mired in shortcomings of their own. Because of their general unwillingness to utilize direct action or mass mobilization tactics, these major environmental organizations—National Wildlife Federation, Environmental Defense Fund, Audubon Society, League of Conservation Voters, Sierra Club—appear to deal more in respectability politics than the massive popular demonstrations needed to motivate sustained action. Ossified by beltway politics and the need to remain respectable amidst the mainstream Democratic Party, these “Big Greens” hold intransigently to their traditional organizing patterns and lose support because of it.

For Uehlein, the bottom line is that “both movements are losing.” Traditional environmentalism fails to elicit the nation-stopping turnout of 1970’s first Earth Day, and traditional unionism has been greatly weakened in many sectors by multinational corporations and weak labor-rights enforcement. Both movements, in their most institutionalized forms, are dominated by white male voices which fail to represent the women, people of color, and working poor who are most threatened by corporate greed and climate catastrophe. When operating in separate “silos,” labor and environmentalism fight each other instead of their common enemy.

Yet despite the failings of Big Green and Big Labor, these movements have so much to gain from cooperation. The federal jobs guarantee, a cornerstone of the Green New Deal and other major climate legislation, would benefit organized labor more than any legislation in the past several decades. According to Uehlein, such a program would “drive wages and benefits up and allow unions to do what they do best: Negotiate good contracts.” The infrastructure necessary to transition the U.S. to a sustainable power grid would employ millions of Americans across the country, and vigilant oversight could ensure fair workplace conditions that new unions to grow and flourish. And these new unions could bolster the waning power of American workers. History shows us that labor’s greatest victories follow minority inclusion, like women in the “9to5” movement or black workers in the Congress of Industrial Organizations [the “CIO” in AFL-CIO]. Recent victories at Starbucks and Amazon rejected the parenting of established unions, garnering more widespread support by organizing themselves. With the prominence of Black Lives Matter, youth climate activism, environmental justice, and indigenous movements, Uehlein maintains that labor must platform and learn from these activists who are actually doing something.

How do we achieve this cooperation and dispel the toxic, false dichotomy of “jobs vs. environment”? Uehlein now heads the Labor Network for Sustainability, a research and advocacy group working out the nuts and bolts of a just transition. He was arrested for civil disobedience protesting Keystone XL, arm-in-arm with Bill McKibben. And he’s in a rock band. The U-Liners have performed with Pete Seager, Tom Morello, and at both the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and AFL-CIO headquarters. Whether singing his originals or covering Jerry Garcia, Bruce Springsteen, and Willie Nelson, Uehlein’s performances are a testament to his beliefs. He changes Billy Edd Wheeler’s lyrics to give the unions due credit and prefaces each set with words of love, empathy, innocence, or revolution. As opposed to capitalism’s propensity for division and addiction, “art and music… arrest life and invite contemplation,” Uehlein muses, and “help [labor’s two beating hearts] recognize each other and come together.” In tributing labor’s rich history of art and music, he marvels at how songs can tell coal miners to “leave it in the ground” with empathy and nuance that prose could never achieve. “Living life is art,” he says, and when business-as-usual fails us, it is the unexpected gracenotes in our music—and our marching—that keep us fighting.

***

This article was originally published here: https://cawei.georgetown.domains/STIA396_Spr22/uncategorized/music-mobilizing-and-making-a-living-on-a-living-planet/