How one man resurrected a dying ecosystem

Toward the end of Sasco Creek Road in Westport, Connecticut, passersby witness a charming landscape change. The typical residential street opens up to a vast meadow where grasses tickle the waists of hikers and birdwatchers. Goldfinches whiz by in yellow flashes; the lucky wanderer stumbles upon an Eastern bluebird. On occasion, bald eagles circle above the forests. Acres of lush vegetation brim with life rarely seen anywhere else in Westport and Fairfield County.

But five years ago, the preserve resembled a barren wasteland. Invasive plants choked out native wildlife. Tangles of hostile weeds overwhelmed the trails and were impossible to penetrate without a machete. Compared to the constant chorus of bird songs that enchants visitors today, the landscape was once nearly silent.

The preserve’s future changed drastically when one Westport resident, Jerid O’Connell, grew frustrated with its decaying state. Over the years, he and other Connecticut Audubon Society members have organized a massive, ongoing volunteer effort to restore and conserve the property. Affectionately known as the Smith Rich preserve, what was once an environmental dead zone transformed into a thriving coastal forest. Local birdwatchers now consider it one of the most important migratory pit stops in New England.

“Change is possible,” Jerid O’Connell, who spearheaded the effort, said. “Change is always fast. And it’s much, much grander and more spectacular than you think.”

The restoration has taken five years, hundreds of volunteers and nearly $500,000 in donations and grants—so far. Workers who oversaw the project agree its success came down to one man—O’Connell.

O’Connell’s background lies not in environmental conservation, but in digital photography and retouching. He embarked on the multi-year journey to save Smith Rich without any initial plan. As a concerned resident who saw potential in the land, his first step was writing a simple (but in his words, “nasty”) email to the Audubon Society back in 2013.

The Smith Richardson Foundation donated the property to the Connecticut Audubon Society in 1982. The three land parcels meant little to the Audubon back then, said Milan Bull, its current science and conservation director and an Audubon member for over 20 years.

“To us, it was an old tree farm that had been abandoned,” Bull said. “It was just one gigantic tangle of invasive vines, and so it was a bit overwhelming to us when we first got the property.”

Community members have recognized the preserve’s potential as far back as 1994, when Yale University researchers published a study on its ecological value. It cites invasive species as a major factor in the property’s degradation.

Invasives developed an advantage over native plants after over-farming depleted Smith Rich’s nutrient soil in the 1970s, according to the study. Culprits like mile-a-minute, garlic mustard and porcelain berry still plague all three land parcels.

“These things become a monoculture on the forest floor so nothing else grows but these invasives,” Bull said. “The whole biodiversity of our coastal forest system declines.”

But O’Connell acknowledged Smith Rich’s size, and its proximity to a coastline, meant it had limitless potential. That’s why he sought out donations and volunteers for a restoration project.

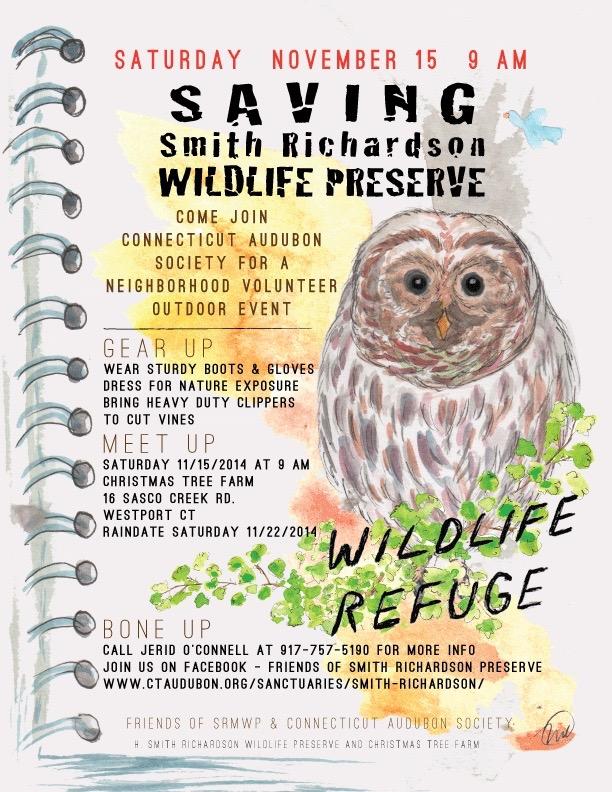

By Nov. 15, 2014, O’Connell and the Connecticut Audubon Society had amassed nearly 100 volunteers to whack weeds and clear space for trails. They consisted mostly of teenagers from local volunteer organizations, including the Service League of Boys and Builders Beyond Borders.

“It was the first step in the right direction,” O’Connell said. “You would have thought I was some nutty person wasting a bunch of teenagers’ weekend time cutting vines, but it’s really made a difference.”

The energy from the first day has barely dissipated, O’Connell said. Over the next five years, volunteer days became an annual event, with many volunteers working longer hours and further involving themselves with the restoration plan.

Jory Teltser, a member of the Connecticut Young Birders Club and an incoming freshman at Oberlin College, is one such volunteer—he attended the first clean-up and every clean-up since, contributing over 30 hours of work.

“Seeing how [the preserve] has transformed over the last couple of years was pretty amazing,” he said. “It really has become just a hidden treasure in town, and it can really show people that a lot of hard work pays off in the end.”

Two years of fundraising and volunteering finally resulted in what O’Connell described as the turning point: a $145,000 matching grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation in 2017. To obtain it, the Connecticut Audubon Society had to raise $134,000—a figure they exceeded within a year. The money contributed to ongoing work, including trail maintenance. The ecosystem at Smith Rich has flourished ever since.

The property is known as a migratory “hotspot,” meaning birds, butterflies and other insects will stop by to fuel up along their exhausting migration routes. Today, Smith Rich boasts meadows rich with seeds and forests rich with fruit—perfect for hungry travelers along the critical Atlantic flyway.

“The sheer number of birds during migration at this spot is greater than any other place I’ve seen in the state,” Teltser said. “In these fields I’ve seen hundreds and hundreds of birds at a time.”

The high number of birds also serves as an indicator for general environmental health—including the health of humans in the area.

“If we have healthy habitats from birds, we have healthy habitats for ourselves because we require the same things the birds do,” Patrick Comins, executive the Connecticut Audubon Society’s Executive Director and a restoration project leader, said. “Where birds thrive, people prosper.”

Nowadays, the society also focuses on building a community around Smith Rich. Aside from volunteering, the restoration has created educational and cultural opportunities. That includes teaching the next generation of environmental activists how to enact change in their community.

“We have issues of national and even international concern right here in Connecticut,” Comins said. “We have birds that are globally vulnerable to extinction. Connecticut is absolutely critical to their survival. You can make a global difference by acting locally.”