Billy Metcalf Photography/CC BY 2.0

Billy Metcalf Photography/CC BY 2.0

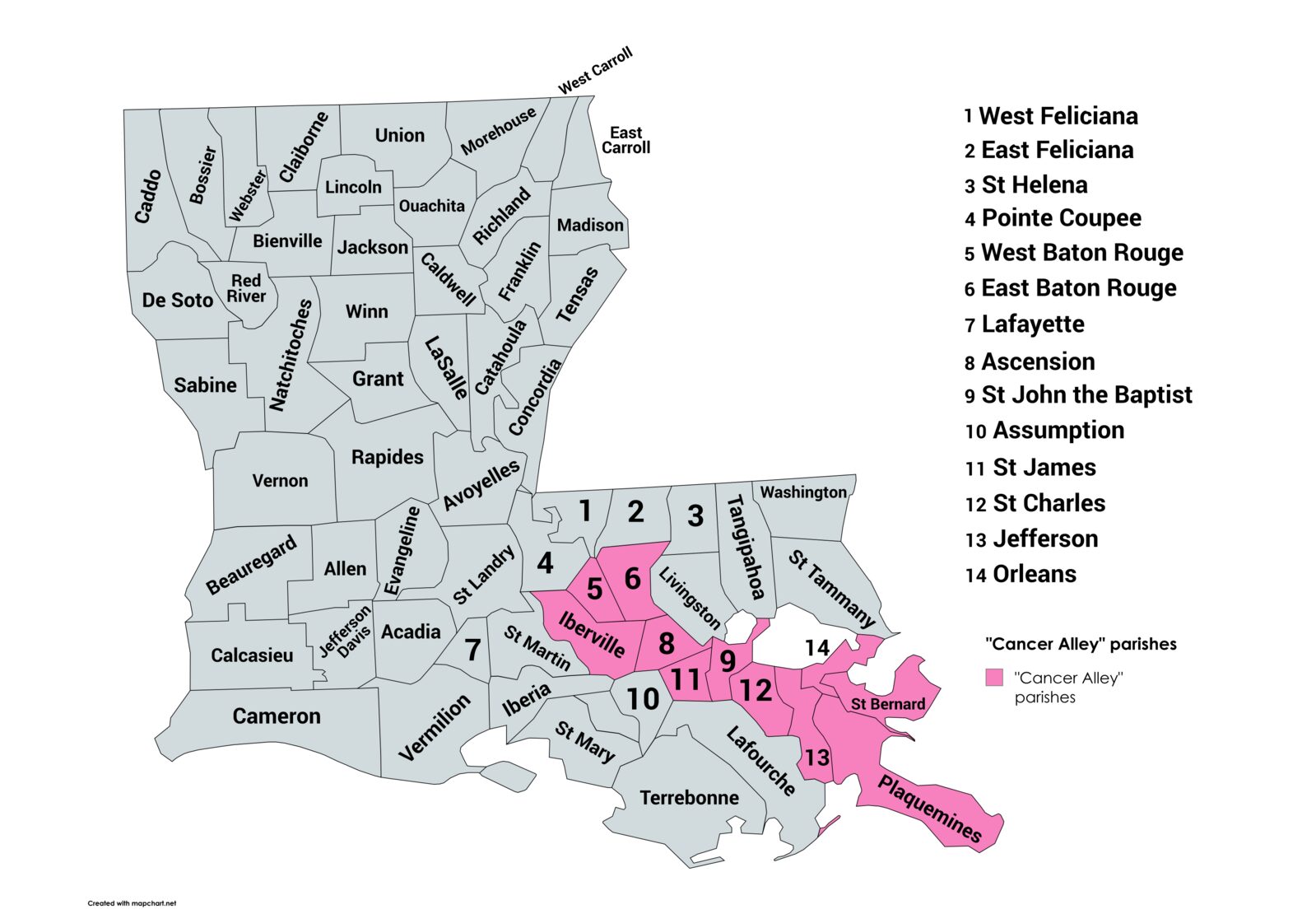

Could you ever imagine living in a community that you love dearly but is toxic to your body? Ashley Gainard is a 48-year-old mother, breast cancer survivor, and lifelong resident of a region colloquially known as “Cancer Alley” — a group of communities located along the Mississippi River in Louisiana that live under a dark cloud of fossil fuel and chemical pollution.

Over 150 chemical plants dominate the industry of the area and according to ProPublica, “Black residents in southeastern Louisiana bear a disproportionate cancer risk from industrial air pollution.”

Gainard has not only lived in Cancer Alley her entire life, but her family is prominent within the community. Many of the buildings in the area are named after her family, and it is Gainard’s love for her family and community that keeps her motivated to advocate against the toxic fumes within the area.

The interview below has been edited for clarity and length.

CIARA THOMAS: How did you initially find out about the risks in your community?

ASHLEY GAINARD: Living in this community, you start to notice that some of the things we find normal aren’t normal. Like all of these diagnoses. I have eczema. As a small child I had bronchitis as well as one of my kids. I thought it was something that was just passed down. My mama has not had breast cancer, but she has had several surgeries for benign tumors. Eventually you start talking to other women and they’re like, “Oh yeah, I had a hysterectomy,” “I had a miscarriage.”

CT: Wow, it’s so sad to realize that all of these health issues that are normal in this community are in fact abnormal to everyone else.

Our conversation led to how the community’s economy continues to be dependent on the factories that are hurting them. A site of considerable industry, Cancer Alley is home to 25% of the nation’s petrochemical production.

AG: The industry that is located in their neighborhood gives money to the community.

CT: So, they know that this is an issue and they’re trying to pay y’all to be quiet?

AG: Exactly. It’s hush money. It’s a tactic to keep the community quiet to not put them on blast. They’ll even visit the schools to teach students how they work in the factories once they graduate. You don’t have to be smart enough to get a degree, we’re going to teach y’all how to work with your hands. Even though it might be a little dangerous working on chemicals, but you’ll walk away with a trade. It’s heartbreaking.

Gainard expressed her frustrations with the continuous cycle that is taking place, and the lack of people who are standing up against these injustices. One may ask why she would choose to stay in this community. One that is continuously harming her friends and family, and where the community often seems silent.

AG: I’m tied to the life here. I was raised here in Donaldsonville. My family was influential here, with many street names and buildings being named after them (Jones and Stewart). We even have a graveyard where my family donated the property so that the community can know its history of who the first Black doctor was and other important figures.

My family members are buried there, and my mom and dad still live here. My great-great grandfather came here from Haiti as a free man. I can still walk the land where my family started. I love it here, so that’s why I stay.

Gainard also notes that moving somewhere else would not necessarily fix the problem. Across the United States, black and hispanic communities are disproportionately impacted by environmental issues like pollution. Since the problem is so widespread, picking up and leaving doesn’t necessarily work as a solution to many people from marginalized communities. Communities like Gainard’s face deeply personal issues which are very intentional and the only way this can change is if all communities not only recognize it but also act.

When asked about the contributions that she makes in her community to fight the pollution in the air, Gainard brought up the organization she founded called “Rural Roots Louisiana”.

Her organization focuses on “fighting environmental justice, empowering [the] youth, building stronger communities, and promot[ing] social equity.” Gainard takes pride in her work in advocacy and is trying to be the voice for her community. She hopes to one day push the factories that are producing the pollution in the air out of her community. Her final thoughts are that “the voices of the people should matter more than the profits of polluters.”