Volunteers work together to organize food at the San Francisco Marin Food Bank (Photo by Sejal Govindarao).

Volunteers work together to organize food at the San Francisco Marin Food Bank (Photo by Sejal Govindarao).

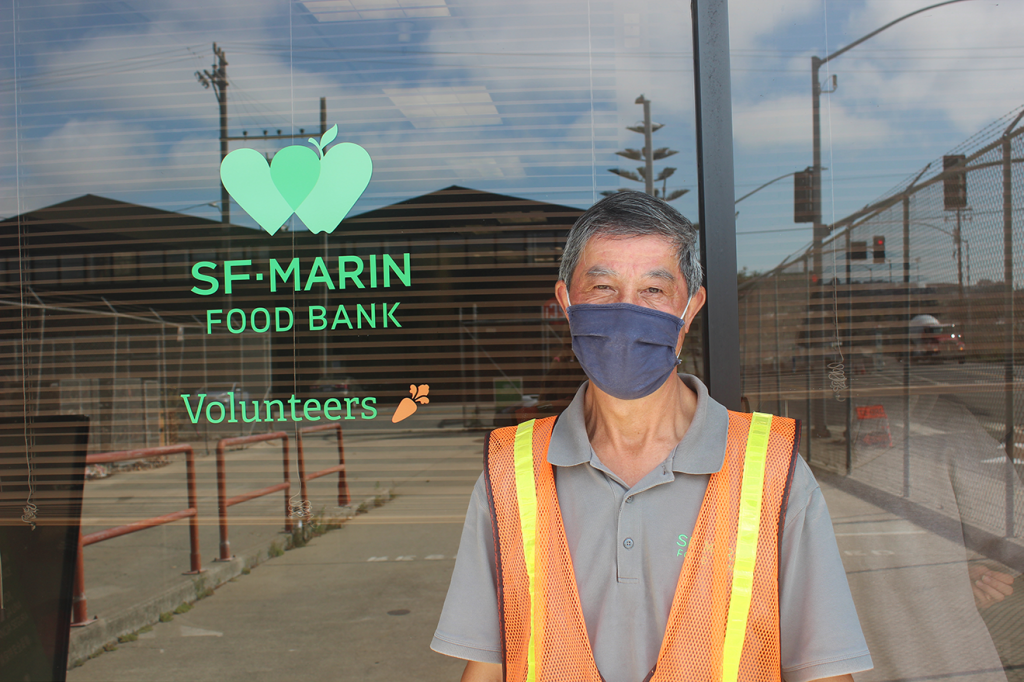

SAN FRANCISCO—George Kwong’s passion is to make people happy through food. The 63-year-old is a long-time resident of San Francisco and held his job as a hotel kitchen supervisor for 34 years. In March 2020, he was a victim of the pandemic’s economic downturn. His employer put him on furlough, making him one of hundreds of thousands in California that lost their jobs in the disproportionately impacted food service and hospitality industry since February.

“When we first got furloughed, we thought it was only a couple months, like two months, three months,” Kwong said. “And then they keep extending, extending, extending. The city opened back but the hotel didn’t have enough conventions, meetings, or tourists so they don’t have the revenue to call everyone back to work.”

The month he was put on furlough, George started volunteering at the San Francisco Marin Food Bank to help out his community. Months later, in June 2020, the food bank hired Kwong. He plans to continue working there even after he returns to his job at the hotel.

“Working at the hotel wasn’t just a job, it’s what I like to do,” he said. “If people are happy with the food you make, you are happy too. Same thing, when you serve the community, you help people and make them happy.”

As the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a global economic crisis, many were out of work and unable to afford food. Out of the 2.6 million people in California who lost their jobs between February and April 2020, 64% were in jobs in low paying industries which disproportionately employ people of color.

In early August, 2021, over a year into the pandemic, new COVID-19 cases reached the highest daily average since January 2021––coinciding with the rise of the Delta variant. In the United States, communities of color have been disproportionately hit by COVID-19 due to economic inequities that stand to continue in a post-pandemic world while wealthier majority populations return to “normal life.” This trend held true in San Francisco, where people of color, 54.8% of the population, accounted for 63.3% of total COVID-19 cases as of August 28, 2021. The case rate was even more disproportionate at the beginning of the pandemic, from April 2020 through August 2020, when Latinx residents accounted for over half of the cases each month despite making up only 15.2% of the population.

When California became the first state in the U.S. to issue a statewide stay-at-home order in March 2020, communities needed adaptation and expansion of food assistance initiatives. In response, the city of San Francisco partnered with local non-profit and community-based organizations to minimize food insecurity through the pandemic. The city spent more than $80 million in the 2021 fiscal year to create new food security programs and initiatives, said Susie Smith, Deputy Director of Policy and Planning at the San Francisco Human Services Agency.

Smith said that this budget “provided for continued support for food access through local food banks, programs for older adults with disabilities—people (who) were specifically being asked to stay at home—as well as meals for unsheltered people and meal delivery options for people (who) needed to isolate and quarantine.”

The San Francisco Marin Food Bank partnered with the city government to pilot pop-up pantries which provide produce free of cost.

“Investing in the bank was our mass distribution effort,” Smith said. “(The food bank) created a robust network—about 20-22 pop-ups across the city that the food bank had organized.”

Meanwhile, the nonprofit Meals on Wheels San Francisco delivered 2.4 million meals and served 16,460 individuals overall in 2020, three-times the number of people served in any prior year; The organization broadened their services beyond their pre-pandemic demographic of senior citizens, according to Jim Oswald, director of marketing and communications at Meals on Wheels San Francisco. Meals on Wheels partnered with the city to become the intake for the Isolation and Quarantine Line—a hotline for individuals to call if they were impacted by COVID and could not get groceries. According to their blog, nearly 87% of meal delivery requests through the hotline are in African-American and Hispanic communities.

Another program, Farm to Family repurposed wasted produce from farms and delivered it to food banks. The federal and state governments expanded Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits to increase access through Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer (P-EBT) cards, which repurposed the money towards summer meals for low-income students to spend on food.

Hilary Seligman, professor at the University of California, San Francisco, has studied food insecurity and hunger policy. Seligman said, “This layered intervention is a quilt of things between school meals, Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) changes, SNAP changes, pop up pantries and Farms to Family. Through all those things together, I think we really kept food insecurity rates much, much, much lower than they would have been.”

While the city of San Francisco and local organizations innovated to serve food insecure populations, some initiatives were built for the short term and lacked the infrastructure to be durable, Seligman said.

For instance, Great Plates Delivered, a unitary federally funded California emergency food project, ended its food assistance program in California after 18 months. And Farm to Family, though federally funded, lacked infrastructure at the state level to be distributed fairly through the state of California, according to Laura Reid, Director of Communications at CA Association of Food Banks. Keely Hopkins, communications manager at the San Francisco Marin Food Bank, said she recognized anecdotally that the food bank might not be serving certain demographics as well as others and that they hope to take a more data driven approach to inform targeted outreach in the future.

In a perfect world, Seligman said, fewer people would rely on nonprofits and community based organizations for food.

“Ideally, we would have a social safety net in place that was provided equitably to all people so that there weren’t people who fell through the cracks,” Seligman said. “We’re not there.”

Local and state governments are limited in their ability to spend on social programs because they can’t run deficits, according to Michael Hankinson, professor of political science at George Washington University. They can take out debt, but that starts to hurt them in the long run.

Still, the pandemic brought broad attention to a pre-existing need for policies to address food inequity in the long term––and illuminated a path toward durable and equitable food policy initiatives, according to Samina Raja, professor of urban and regional planning at the University at Buffalo and leading expert on building healthy and equitable food systems.

“Society at large felt there was a crisis because the wealthy and majority populations were bearing the brunt,” Raja said. “That’s why everybody started paying attention (to issues of food insecurity). That kind of crisis already exists in my city in the black neighborhoods. I have elders, black elders, who are routinely without food, who are routinely without deliveries, who do not get calls from their social service workers. That is not new for them. In fact, some of them were like, ‘We know what to do, because we’ve seen this before.’”

She continued, “Going forward, local governments would be smart by investing in (policies) and programs that center Black communities and Brown communities because they actually know what their neighborhoods need. The lesson from COVID is when you move forward beyond the crisis points, remember that community networks are essential for developing thoughtful food policy.”

According to Raja, one way to bring Black and Brown communities into the conversation is to establish Black and Brown-led advisory groups within local governments. This develops more infrastructure for food initiatives by ensuring communities of color are represented in policy deliberations.

This method is being tested in Baltimore, where the city government implemented a Food Policy Council. Resident Food Equity Advisors work closely with City staff to provide recommendations that support the community with nutritious and culturally appropriate food.

Raja recommended another solution involving the consultation of communities of color––reforming urban agriculture. This may come in the form of community land trusts that are controlled by Black and Brown households in Black and Brown neighborhoods.

“(A land trust is) a specific mechanism that allows communities themselves to take control of land and decide how it serves the needs of residents and neighborhoods of color,” Raja said.

Unless paired with policy measures to ensure affordable housing, increasing property value can be counterproductive for residents of low-income neighborhoods, who may be pushed out by increased rent or property tax. Organizations like the Dudley Street Initiative implement strategies that encourage development without displacement, Raja said.

Entrepreneurial Grant Programs for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color communities also aid in the prevention of food insecurity because they allow “Black and Brown communities, immigrant and refugee communities to start up their own food businesses,” Raja said.

Yet, according to Seligman, these initiatives are easier to implement on the local and state level. California has already implemented a universal school lunch program, School Meals for All.

“A lot of the policies in place for government programming systematically exclude people,” Seligman said. “They are rooted in a desire from previous generations to limit access to that programming. And while there are efforts to unwind many of those policies, the Federal systems tend to do this unwinding slowly.”

While community organizations provided short term solutions during the economic precarity of the COVID-19 pandemic, those invested in food security may look ahead to the next renegotiation of the Farm Bill in 2023. According to Seligman, 80% of the funds included in the Farm Bill are dedicated to federal nutrition programming, presenting a substantial opportunity to change the infrastructure of federal support for the food system across the U.S.

—

About this series: The Planet Forward-FAO Summer Storytelling Fellows work was sponsored by the North America office of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the Fellows were mentored by Lisa Palmer, GW’s National Geographic Professor of Science Communication and author of “Hot, Hungry Planet.”