Carlett Badenhorst/Unsplash

Carlett Badenhorst/Unsplash

On July 4, the World Meteorology Office announced an upcoming El Niño in the southern hemisphere and I was immediately taken back to 2015. I had just started my first job in humanitarian response at the peak of an El Niño-induced drought in Lesotho.

The drought was severe, drying up most rivers and leaving Lesotho’s largest water reservoir, Katse Dam, at only 50% capacity which declined even further following the El Niño. Many fields were left unplanted and those that were planted yielded very little, everything was barren.

According to National Geographic, “El Niño is a climate pattern that describes the unusual warming of surface waters in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. El Niño is the “warm phase” of a larger phenomenon called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

Led by the work of Sir Gilbert Walker in the 1930s, climatologists determined that El Niño occurs simultaneously with the Southern Oscillation. The Southern Oscillation is a change in air pressure over the tropical Pacific Ocean. When coastal waters become warmer in the eastern tropical Pacific (El Niño), the atmospheric pressure above the ocean decreases.”

The situation in 2015 and 2016 was quite alarming as we witnessed the impacts of El Nino within our communities and saw how our community members were faced with the despair, frustration, and hopelessness of failing crops. As climate change is expected to increasingly magnify the effects of El Niños, countries like Lesotho will need to implement effective measures to address the worsening impacts.

Earlier this year, Lesotho Meteorological Services issued a press release predicting drier conditions starting in October 2023 and likely to continue until March 2024. This period coincides with Lesotho’s planting season, and the lack of rain coupled with warmer temperatures could adversely affect agricultural production.

Although it is still uncertain whether the country will be receiving average to below normal rainfall this rainy season, the government is prepared to face the worst. Additionally, Non-Governmental Organizations and developmental partners such as FAO, are actively seeking funding to respond quickly in the event of a drought caused by El Niño.

“We cannot confirm that we will have a drought because the Southern Oscillation is not yet established, and we do not want to cause panic. We, however, still advise our farmers to be cautious. Farmers are urged to seek expert advice and use the available agric extension services to maximize their production and minimize losses should the country experience drought,” said Rammolenyana Lethaha, weather forecaster at Lesotho Meteorological Services.

During the 2015 and 2016 El Niño, several organizations worked together to help communities deal with the impacts of the drought and recover from the effects. Among the actors was the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Lesotho, which assisted communities in building their drought resilience.

According to David Mwesigwa, Emergency and Resilience Coordinator at FAO Lesotho, some of the interventions included researching early-maturing seed varieties for crop production, while other interventions were implemented to improve livestock care.

These included drilling boreholes in water-scarce communities that capture groundwater for reuse and establishing animal drinking points to provide water for animals. Interventions by other actors included training smallholder farmers on climate-smart agriculture techniques, distributing water to water-stressed communities, and providing food aid.

“One of the significant lessons was to strengthen stakeholder coordination to build a more coordinated response team and inclusive efforts (between communities),” Mwesigwa said. Coordination across communities will reduce redundancy, ensuring that available resources reach a larger population.

He later mentioned that vulnerability assessments and the National Information System for Social Assistance (NISSA) database were beneficial in identifying vulnerable households and communities. Strengthening of such tools is crucial for ensuring the shortest possible response time and bringing the right solutions to communities who need them.

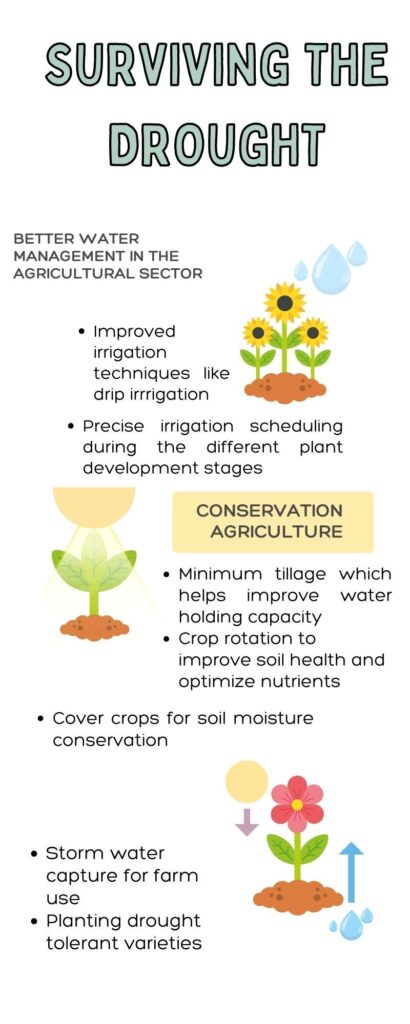

Mwesigwa also noted specific ways that Lesotho can adapt to agricultural stressors in the future. “The country’s irrigation coverage is currently at only 2.6%, which means the country heavily relies on rainfed agriculture. Hence, investing in irrigation is crucial to improve agricultural yields,” he said.

As farmers plan for the future, they should aim to increase their yield in both average and above-average rainfall years, in order to prepare for droughts. Additionally, they can intensify their water harvesting efforts during years with ample rainfall, to have a reserve supply of water for farming purposes.

“It is crucial for Lesotho to have contingency plans, be self-sufficient and stop relying on South Africa for seeds and fertilizers” Mwesigwa said. Relying on South Africa positions Lesotho at a vulnerable position during climatic shocks as South Africa will need to satisfy its farmers first. Lesotho’s needs may not be met or the supply may come very late into the planting season.

“Adopting climate-smart agriculture techniques and enhancing land and water conservation practices can also contribute to boosting productivity. Strengthening early warning systems is also necessary to mitigate risks. Lastly, coordination and information sharing should be improved to ensure efficient execution of plans,” Mphatsoane said.

Thakane Mphatsoane, a farmer from Nazareth in western Lesotho, describes the impacts of the 2015 and 2016 drought as detrimental to her farming business. The El Niño presented a major shock, as she had just started her agri-business. “I lost everything during the drought, it was (too) dry and hot for any of my crops to survive and I did not have any alternatives,” Mphatsoane said.

She also mentioned that one of the challenges has been the emergence of pests, most of which could not be controlled by the organic pest repellents they had been using, forcing her to buy chemical pesticides to control the situation.

Mphatsoane believes this invasion of pests is a result of the changing climate and was exacerbated by the extremely dry and hot conditions during the El Niño. According to the US Department of Agriculture, climate change and especially the increase in temperature will increase pests populations and their geographic distribution.

With the help of Lesotho Meteorological Services, other relevant ministries, and developmental partners’ guidance, Lesotho can move from panic every time a disaster hits to being prepared and more resilient to these shocks.

Hopefully, the country can reach a stage where farmers can handle different climate-related surprises and adapt effectively. There is a need for the government to invest more in climate-smart agriculture to help farmers adapt to the changing climate and keep their family’s food secure.

After facing a severe drought when she first started farming, Mphatsoane has now recovered and even added farming tunnels to her farm. These tunnels are useful during extreme temperatures and rain-deficient periods.

Local farmers face more than just a lack of rain. They also have to deal with alternating periods of low and excessive rainfall, which can be challenging. This has caused Mphatsoane to come up with creative solutions to combat this issue, such as building a fish pond on her farm.

“In preparation for future dry spells, I have captured storm water and continue to construct more ponds which will reserve water that I can use for irrigation. I also intend to plant drought resistant crops during the dry period,” Mphatsoane said.

Research indicates that climate change will worsen and cause more climate shocks in the near future. For farmers like Mphatsoane, adapting to drier planting seasons and more extreme weather events is crucial.

“I believe it is important for farmers like me to explore stormwater capturing and store enough water for the dry seasons. It is important that we irrigate our crops and not depend entirely on rainfall. As farmers, we should also invest in drought resistant seeds, get access to weather outlook and receive expert recommendations on what plants to grow in various climate conditions,” Mphatsoane said.