Paul Leoni

Paul Leoni

Sitting circularly with people in a traditional Saami Indigenous nomadic tent – feeling the warmth of the fire and the softness of a hide at my hands – I watched conversations happen in many different languages. Yet one language spoken was universal, and that was the love for food. As I sat and listened, I felt many questions rush to me. What would your community’s food system look like if you had collective control over your foods? What can we learn from history that we can carry into building a better tomorrow?

Take a moment to envision an alternate reality that encapsulates the past while imagining the future. Personally, when I see collective and community controlled food systems, I see happy, healthy people who can cultivate and harvest food on a local level that works in alignment to the natural world, rather than against it. Indigenous communities around the world have been engaging with their food systems in this way since time immemorial and continue to do so through the passing of intergenerational knowledge.

As Indigenous communities in North America are sovereign nations existing within a settler colonial nation, their fight to enact food sovereignty has been and continues to be ongoing. Food sovereignty can be described as the “right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.”

While attending the United Nations World Food Forum (WFF) at the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) headquarters in Rome, Italy, I had the immense honor of attending a session called, “Safeguarding Indigenous People’s Food Systems for Better Nutrition.” The session brought together three Indigenous panelists from around the world to talk about their efforts and experiences in enacting food sovereignty within their own communities.

After the session, I was able to meet Daryl Kootenay, the Global Indigenous Youth Caucus Focal Point for FAO, to learn more about his specific community’s food sovereignty practices and how it ties them to their place of being, fosters nutritional practices, and overall brings people together through connection to food.

Kootenay is from the Iyarhe Nakoda Nation in Southern Alberta, a part of Treaty 7 Territory, and is also a part of the Navajo Nation in New Mexico. He is a land based educator, a singer, dancer, culture keeper, husband, father and so much more. As he states, “I hold many different roles. I teach as a faculty member at the University of Calgary and the Banff Centre for Indigenous Leadership. I co-founded a Nakoda Youth Council that we take annually to the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous issues, and I’m also the Co-Executive Director for the Howl Experience.”

Kootenay began his introduction with an explanation of the people and places he comes from. This is very common in Indigenous communities, as doing so honors relationships to the people and places that make someone who they are.

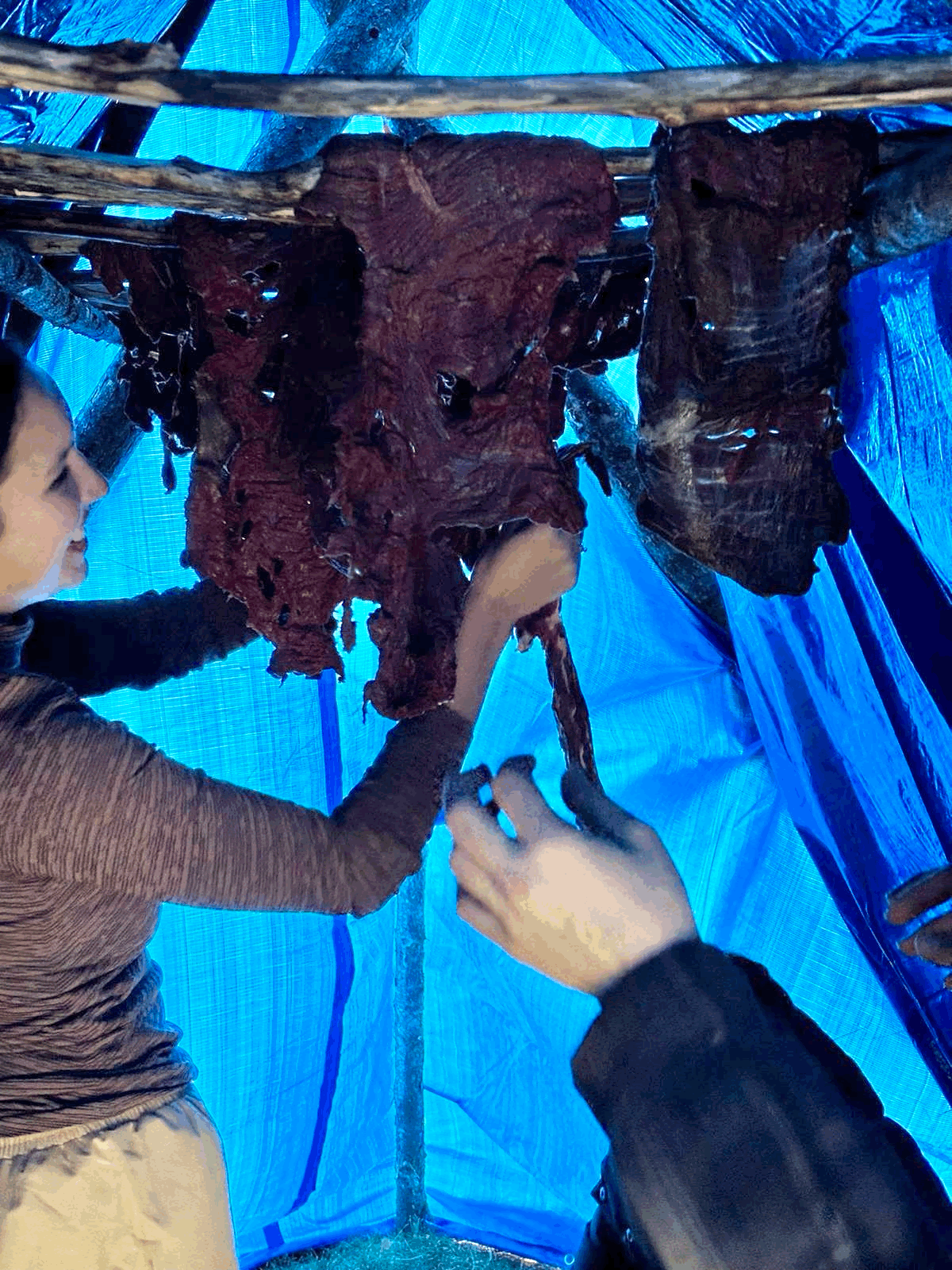

The Iyarhe Nakoda, or Stoney Nakoda, communities are the original “peoples of mountains.” “Iyarhe Nakota, we’re mountain people and are well known for big game harvesting,” Kootenay said. Elk meat is one of the many Indigenous game foods that Kootenay specifically relates to and educates others on. Part of his role as an educator is to engage both Indigenous and non-Indigenous folks in food sovereignty. He does that by coordinating camps as a part of the Howl Experience, as he knows it takes collective community efforts to successfully accomplish these types of traditional activities.

Due to settler colonial violence, such as forced removal of Indigenous people from their homelands, enacting food sovereignty has been no easy feat. One reason that Indigenous peoples, like Daryl’s community of the Iyarhe Nakoda Nation, have been forcibly removed is through the creation of Parks Canada. The creation of Banff National Park led to the removal of Stoney Nakoda from their homeland, in turn causing disruption to their ways of being and traditional practices of hunting and gathering.

There is a distinct difference between Indigenous communities and settler societies, and the ways in which each believes people should interact with plants, animals, and other non-human beings. The conservation method of Parks Canada is rooted in the belief that nature should be untouched and exists separate from humans, whereas Indigenous communities believe in reciprocal and respectful interactions with their environment. This belief is central to the ways in which food sovereignty practices are carried out.

These ideas are spoken of in an article that highlights the voice of a Nakoda elder, Sykes Powderface. Powderface declares that, “It denied our ancestors from accessing an area that has sustained who we were from time immemorial… The so-called conservation/preservation, particularly for wildlife, what does it mean? It means something different to us than the western world. To the western world it means money, to us a belly full. That’s what it means.”

Despite colonial systems working against Indigenous peoples’ efforts to maintain food sovereignty and community connections to land, Indigenous people and their foodways continue to thrive. Creating spaces where people can connect to their food on a deeper level is one way this is done, but also by using intergenerational knowledge to carry forth ways of being into the future.

Kootenay spoke about recreating a type of learning environment where knowledge that’s shared is based off of the way Stoney people operated their harvest camps in the past. This type of knowledge is based on long-standing connection to a place. Indigenous knowledge itself is scientific and the ways of knowing are created through the lived experience.

This is further described in a journal which states, “Traditional foodways are based on an intimate and spiritual connection to the land and entail a reciprocal relationship that must be actively maintained… Indigenous knowledge derives from traditional teaching, empirical observation, and spiritual insight.”

None of this work could be done without the head and the heart. While at the WFF, Kootenay commented on how he notices that in these spaces there is a lack of people leading with their hearts. He beautifully describes, “I think that’s primarily the main cause for how things are taking the wrong turn today, because there’s a lot of policy, there’s a lot of academia that requires a lot of your brain and your head and lack of love.”

Kootenay was given a Native American name, Wocantognake Itancan, which is Lakota for “the one that leads with his heart”, and as he states, that is exactly as he tries to do while engaging internationally and within his local community. The WFF was about bringing people together for their love and knowledge of foods. Kootenay’s food sovereignty efforts and his role as an educator really embody the goals of what WFF is all about.