How to design for privacy and sustainability — even in the Panamanian jungle

By Daniel Fernandez and AnnMarie Hilton

Students from across the globe are traveling to the heart of the Panama jungle to learn everything from the fine points of farm-to-table cooking to the most efficient configurations of iguana farming. Taking up residency in the jungle may prompt thoughts of giant bugs, stifling heat, and limited electricity. But what Kalu Yala’s students really need, according to the design thinking intern Katie Cappola, is a place to “fight, f*ck and fart” in peace.

Jimmy Stice, the founder of Kalu Yala, left it up to the design thinking interns to find a solution for the lack of privacy in this communal living arrangement.

With rest, recreation and human behavior in mind, this semester’s design thinking team faced the challenge of designing residential structures which provide privacy and match Kalu Yala’s aspirations for sustainability.

Privacy

Privacy would seem an intuitive aspect of designing homes, but the ranchos the interns call home are without walls, which makes privacy a rare commodity at Kalu Yala. In fact, interns’ only “private” area on campus — their sleeping space — is either an air mattress or a hammock. While this satisfies the program’s desire for an immersive, sustainable jungle lifestyle, the design thinking interns agreed that everyone could use a little more privacy.

The interns say they have been working on plans for two types of residential structures: “Tiny homes,” which eventually will house residents at Kalu Yala, and smaller “staff shacks” for the full-time staff who currently live on platforms a few hundred feet from Town Square, the heart of the Kalu Yala’s campus. These staff shacks will provide staff members with greater privacy and a space of their own, but unlike the tiny homes, they will not have separate bathrooms or kitchens. The design thinking interns hope this will encourage staff members to stay in their positions longer.

“This is a solution to give staff a place that makes them want to stay longer because we do have a high turnover rate,” said Cappola, a student at Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pa. “We’re living in the jungle. Living here is hard, and it’s hard to have a family here. Those things aren’t exactly conducive here.”

The lifestyle is very public and the interns and staff are constantly interacting with each other and the beautiful valley surrounding them. But they hope to create more opportunities for balance through the construction of these homes and a new round of ranchos. One of Kalu Yala’s ultimate goals, Stice says, is to have people who will call the valley their home, or at least a second home. The interns in design thinking, one of several internship programs available at the Institute, recognize this goal will be better met with more opportunities for privacy.

In a community that only has one building with walls — a media center created by a VICE documentary team — it seems fairly simple to add more privacy. But at Kalu Yala, privacy and sustainability are not mutually exclusive. The interns must be sure that their privacy implementations don’t leave a large footprint.

Sustainable Design

While Strech and Cappola work on the master plan for the town and address these privacy concerns, design thinking interns David Ho and Jack Fritzjunker are finalizing construction plans for the new round of ranchos, which will greet the nearly 150 interns who arrive at Kalu Yala in just a few weeks.

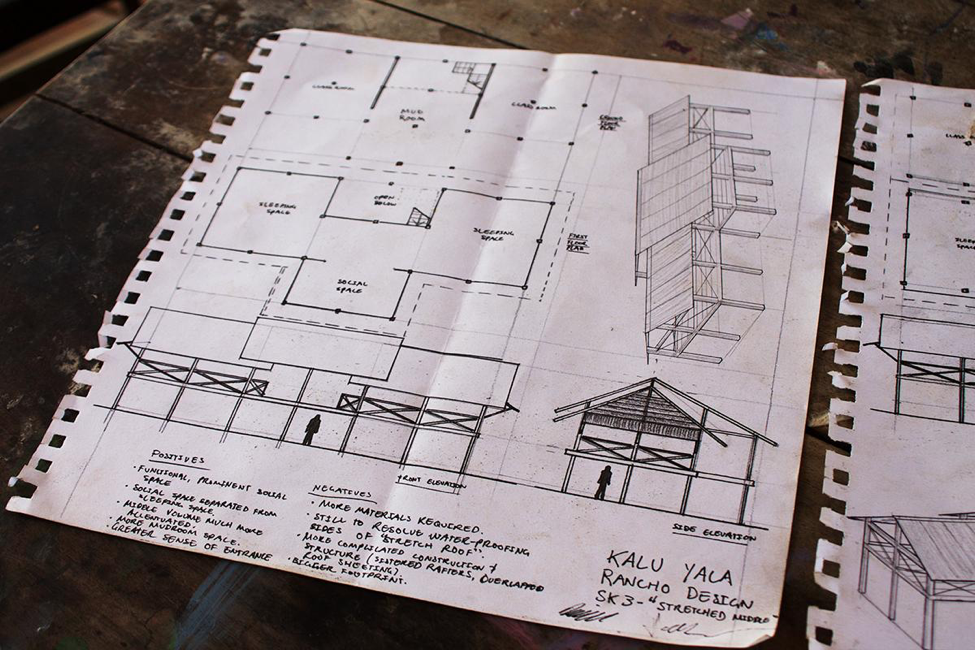

The expansion has provided Ho and Fritzjunker the chance to evaluate and iterate upon past and current rancho designs, which they hope will lead to more stable and sustainable structures. This includes everything from altering the pitch (or angle) of the roof to reduce runoff to using new building materials such as reclaimed wood from the Panama Canal. Beyond these physical changes, however, Ho and Fritzjunker also spoke with Kalu Yala staff and interns to discuss ways of improving buildings for the rainy season and how to make sleeping arrangements more comfortable.

“We synthesize all that information into a bunch of design drivers that we can work towards in our design,” Ho says. “And then we take those drivers and turn them into physical features in the design that solve the physical problems we’re aiming to solve.”

These design drivers include natural factors such as sun, shade, ventilation, and water access, and behavioral elements like where people choose to sleep or how to manage the mud that constantly seems to end up on everything and everyone at Kalu Yala. Ho and Fritzjunker plan to address this grimy reality by creating a mud room, a separate but attached area in the ranchos where people can hang up their muddy clothing before they enter their sleeping space.

This approach, commonly called a “form follows function” model, is one of the guiding tenets of design thinking at Kalu Yala. For Ho, who studies civil engineering in Australia, it’s not just about making things ergonomic, structurally sound, or sustainable, but thinking about how to solve problems.

“When you design, it doesn’t make sense to make decisions arbitrarily,” Ho says. “You should always be working toward a goal.”

After plenty of drawing, sketching, talking, and iterating with these design drivers, Ho and Fritzjunker arrived at a list of features that they implemented into their final rancho design. They also have utilized projects from other interns and staff at Kalu Yala by integrating the often “under-appreciated” guava wood and treating reclaimed wood with a biodiesel product synthesized from waste generated around the institute.

“It’s a lot of improvisation in construction and taking principles that we like and applying them,” Ho says. “It’s about looking at the materials and taking into account things like the environmental value, or the embodied energy of a material — something that doesn’t happen a lot,” adds Fritzjunker, who graduated from Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa.

Ho believes the answer for more sustainable design is not necessarily to focus on regulation, but to envision elegant and simple ways to live better. Ho adds that he’s all for novel solutions and likes “thinking out of the box.” But as he and Fritzjunker have learned at Kalu Yala, it should always be about solving problems, whether it’s tackling environmental design, privacy, or how to handle the torrential downpour during the rainy season.

“I was designing for people who didn’t exist and now I’m designing for people who do exist,” Ho says. “Putting that into practice is one of the most fulfilling things you can do.”

***

Note from the editor: A previous version of this story had misspelled a design thinking intern’s name. This version corrects it. We apologize for the error.