A multitude of unexpected benefits have sprouted after water was added to a river in Tucson, creating an explosion of desert biodiversity.

Hope flows through the heart of Tucson: The Santa Cruz River Heritage Project

“They found the water so quickly, more quickly than I could have imagined,” Dr. Michael Bogan expressed in disbelief. On June 24, 2019, Dr. Bogan, stream ecologist at the University of Arizona, marveled at the water flowing from the outflow pipe into the dry riverbed of the Santa Cruz. Within hours of the water’s release, dragonflies from across Tucson came and found the water.

The rebirth of the Santa Cruz River in Tucson, Arizona is an ecological miracle. The Santa Cruz River flowed year-round until human intervention dried its banks more than 110 years ago. Recently, the City of Tucson decided to pump water back into the river.

After only two years of consistent flow, the river has bloomed to support dozens of mammal, amphibian, and insect species, 135 bird species, 149 plant species, and one very special endangered minnow.

The growing interest in the river has sparked reconnection with Tucson’s heritage. The city is expressing renewed interest in native ecosystems, sustainable gardening, and water conservation.

The Southwestern United States is entering its 22nd year of a megadrought, making water resources more valuable and more scarce than ever before. Lawmakers, scientists, agencies, and governments alike face the challenge of finding innovations to use the smallest amounts of water for the greatest total benefit. A solution to this major challenge flows through the heart of Tucson.

Water Conservation in the Desert

In 2001, Arizona received its first delivery of Colorado River water through the Central Arizona Project canals, allowing the city to move toward more sustainable water use by using less groundwater and investing in stormwater. In 2013, wastewater treatment plants began releasing reclaimed water into the Santa Cruz north of the city as a groundwater reclamation project.

Reclaimed water is a way to recycle the water that comes out of a city as sewage. Water treatment plants clean the water with chemicals and release it so it can soak back into the ground to recharge as groundwater.

The water in the Santa Cruz is cleaned further by natural processes and eventually soaks into Tucson’s aquifer. The City of Tucson says that groundwater recharge with reclaimed water is a safeguard for drought for Tucson. It’s a water bank for times of need.

In 2016, the director of Tucson Water, Tim Thomure, pitched a new project –– expanding the existing Santa Cruz recharge effort. He wanted another pipe to release reclaimed water in the heart of downtown Tucson.

The idea came to life three years later as the Santa Cruz River Heritage Project.

Sciences Elevate the River’s Health

The dragonflies weren’t the only surprise attendees at the “opening day” of the Heritage Project. Organizers projected the event to be tiny; it was barely even advertised. There was one small tent with one crate of water bottles. More than 300 people –– and a mariachi band –– came to celebrate water returning to the river.

“It’s a trickle of water really, but such a small amount of water has created such enormous change,” Bogan told me.

He wasn’t kidding; the Santa Cruz outflows about 1,500 gallons per minute as of 2022. For comparison, the Mississippi outflows around 266,159,000 gallons per minute.

Bogan and his team do continuous monitoring through species counts, species abundance surveys, and remote monitoring, which provide resources to the City of Tucson to keep it healthy and prosperous. Almost in disbelief, he said that, “After only 2 years of continuous flow, we’re seeing an incredible amount of biodiversity.” The rapid recovery of the Santa Cruz River is a beacon of hope to ecologists and citizens alike.

It seems to me that the Santa Cruz River has had a certifiable Field of Dreams moment –– with Michael Bogan as Ray Kinsella. Except, in our desert narrative, the iconic line goes, “If you water it, they will come.”

The Cultural Significance of the Heritage Reach

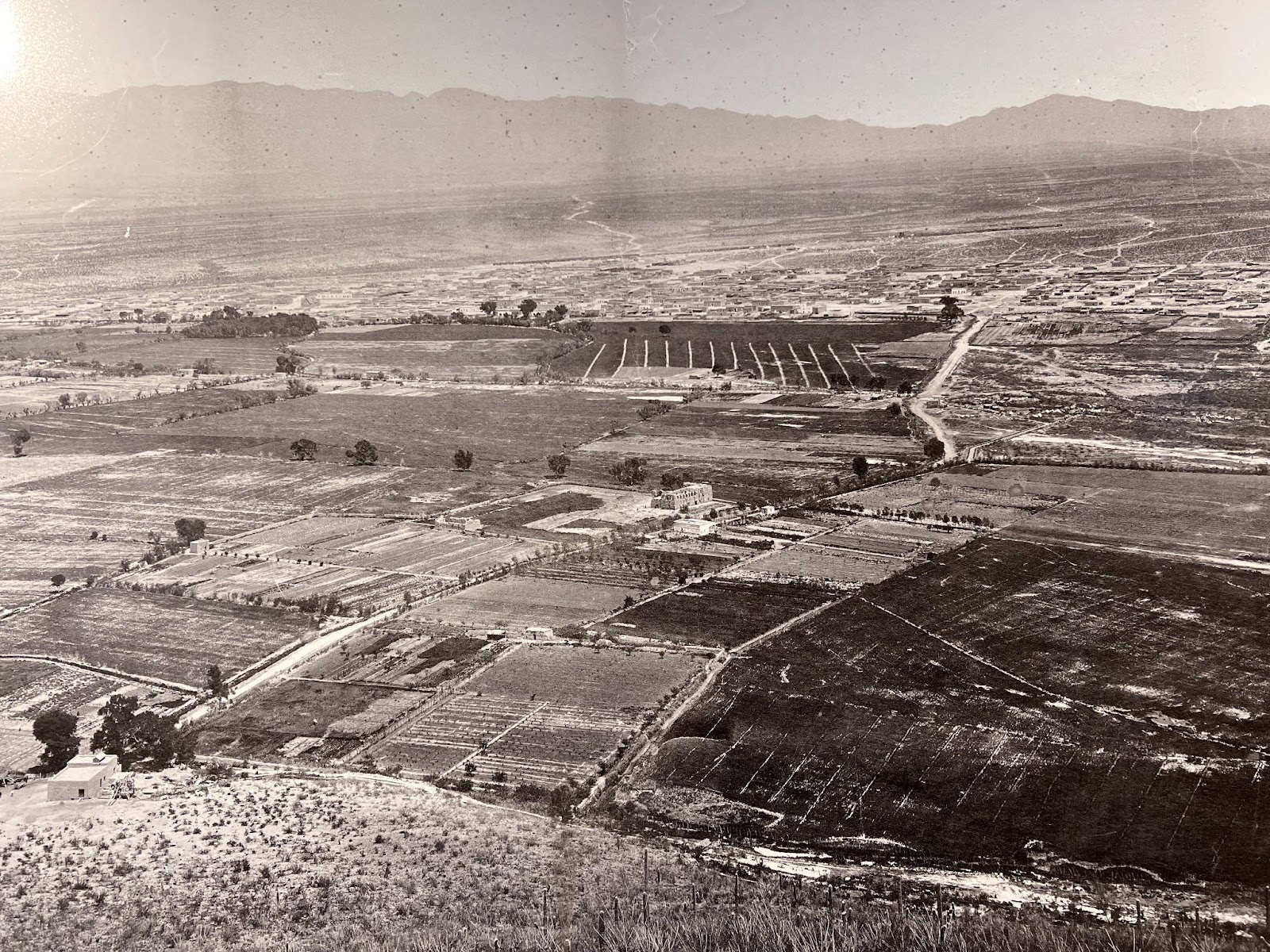

The base of Sentinel Peak (known more often as “A-Mountain”) has been sustaining life for over 4,000 years, making it one of the oldest sites of continuous agricultural activity in the country. The Tohono O’odham and their ancestors, the Hohokam, have been stewarding the land for uncountable generations.

In 1910, businessmen drilled 20 wells at the base of Sentinel peak, drying up the river completely in just five years. Deprived of water, the trees that stood sentinel along the banks of the Santa Cruz for hundreds of years perished. For 100 years, the Santa Cruz has been dry and forgotten, its once-raging waters are now caged in a narrow channel of concrete. It remains as a dry scar on the landscape, like an artery with no blood to pump.

The Heritage Project chose the new pipe location based on the rich history. But why is the return of water to the Santa Cruz called the “Heritage Project” and not the “Recharge Project”?

“Returning water to the river is just one part of what ‘heritage’ means,” Kendall Kroeson told me as we walked the grounds of Mission Garden together. To Kendall, the Heritage Project will be complete if the people, food, and history that Santa Cruz supported for centuries are highlighted along with the ecological success of the river.

The history of Tucson’s birthplace is kept alive by the spirit of resilience and the hardworking volunteers at Mission Garden.

“Tasting History”

Kendall is the outreach coordinator for Mission Garden, a living agricultural museum of heritage fruit trees, traditional local heirloom crops, and edible native plants. It stands on the 4,000-year-old agricultural site.

As I spent time in the quiet walls of adobe around Mission Garden, I spotted hawks soaring in the crisp morning air and petit Gambel’s quail scuttling under the underbrush. Native habitat met flourishing gardens in a brilliant display of desert beauty.

It felt like a sister location to the Santa Cruz –– a sister that is upholding the heritage, biodiversity, and sacred knowledge of crop cultivation alive as she waits patiently for the river to flow again.

Mission Garden is more than a connection to the past, it is an active facilitator of the future. Kendall showed me a fallow plot that would become “the Garden of Tomorrow”.

“We need to make more food, with less land, and less water,” Kendall told me. “It’s a huge challenge.”

The garden plans to showcase drought-resistant plants and drought-tolerant garden practices. It will be an example of sustainable urban agriculture for Tucson and the Southwest. They educate people on how to grow food themselves. Backyard gardening makes food more nutritious, decreases the use of pesticides, and decreases carbon dioxide emissions.

“It is important to know what happened in the past to know what is possible for the future,” says Kroeson. “Here at Mission Garden, we’re here to help people ‘taste history.’”

Generational Change in Tucson

“Four to five generations of Tucsonans have disengaged with the river,” Luke Cole told me.

Luke is the Director of the Santa Cruz Project at the conservation nonprofit, the Sonoran Institute. He and Dr. Bogan expressed the same sentiment when I asked them, “What’s one of the most important impacts you’re seeing from the Santa Cruz?” They both answered that it’s the community change they’ve seen.

I talked to Charles Giles, a lawyer, and avid cyclist who has lived in Tucson for more than 70 years. When I asked him about the Santa Cruz, he immediately responded that “Oh, it had been dead for quite a while.” He’s right. Before the Heritage Project, Tucson’s relationship with the water that once sustained it was all but gone.

New generations of Tucsonans will come to know the river as a place to learn about the value of biodiversity and the importance of water conservation. Dr. Bogan revealed to me that he is approved to create a program that will build a curriculum for educators of all grade levels in Tucson and train 30 teachers over the next three years. He will endeavor to reconnect the newest generation with the river through the power of science and cultural awareness.

The Soul of Tucson

As the world faces massive challenges stemming from climate change, it is more and more important to find the most impactful solutions that need the least resources. The brilliance of the Santa Cruz project is that by adding water, a multitude of benefits have sprouted. Cole noted the importance of this in urban ecosystems, telling me that we need to ”celebrate the multi-uses when they’re there.”

The Santa Cruz Heritage Project is making Tucson more drought resilient, conserving water resources, supporting critical biodiversity, connecting a city to its heritage, and educating a new generation. The flowing river is changing the heart of Tucson.

Something about the sound of water in the desert sings the song of survival to the human soul. Massive change can come from the tiniest of sources, just as a mighty river can be reborn from the smallest trickle.