Avril Silva

Avril Silva

Thousands of hooks, one very long line, and a sea that can no longer afford mistakes. In the Galápagos, where every species seems to tell the story of evolution, “longlining” has become the most divisive word in the fishing business. To some, it is a dangerous step backward; to others, it is a necessary solution.

Longlining – or the practice of deploying thousands of baited hooks on lines up to 100 km, or over 60 miles, long – is extremely efficient at catching tuna and has been used as a method of commercial fishing for more than 20 years in the waters surrounding the Galápagos islands. It’s also the source of major problems for biodiversity in the area, as the long hooks can inadvertently catch and kill thousands of other marine animals in the process.

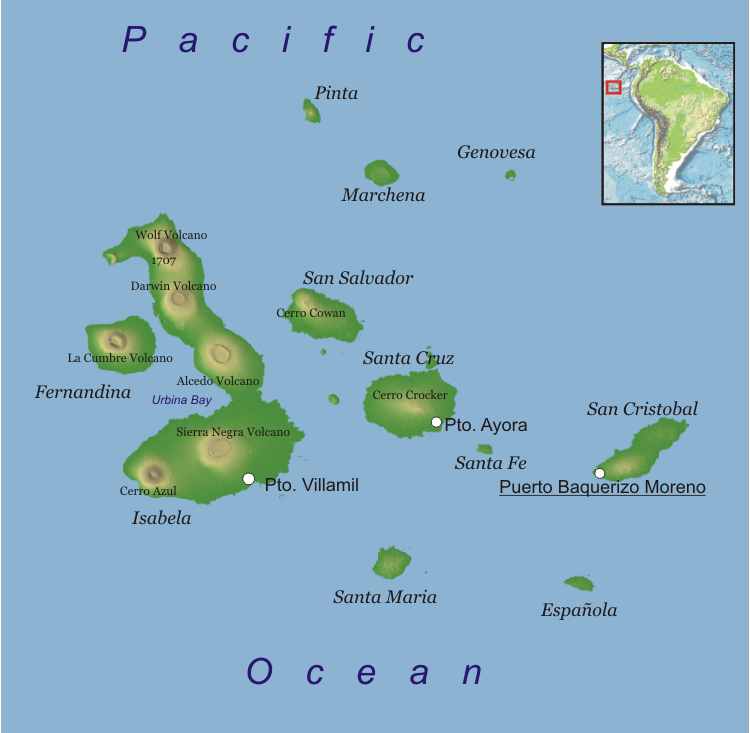

The Galápagos archipelago, famous for its finches, boobies, and tortoises, is also encircled by the Galápagos Marine Reserve (GMR). Ecuador passed fishing-control laws in the area in 1986 and expanded the reserve to approximately 133,000 km² by 1998, according to UNESCO’s World Heritage Center. Over 2,900 marine species have been recorded in Galápagos waters, with 20 percent of them being endemic, or native and only found in the region.

Non-target bycatch often includes endangered sharks, turtles, rays, and seabirds. According to the Galápagos Conservation Trust, Ecuador banned all longline gear in the GMR in 2000 to protect sharks and other threatened species, but fishers and researchers argue that small-scale longlines could boost incomes and relieve coastal overfishing.

Data from a study by the trust found that in 2012-13, a Galápagos longline trial showed staggering bycatch: 4,895 marine animals from 33 species were hooked by just 12 local boats, including 16 species of protected megafauna that include a number of shark species, sea lions, manta rays, green Pacific sea turtles, and more. If longline fishing is restored legally in Galápagos waters, the Galápagos National Park estimates it could catch and potentially kill 10,000 sharks annually. However, researchers like Mauricio Castrejón, still advocate for its implementation and legalization.

Although originally from Mexico, Mauricio Castrejón, Ph.D., considers himself a Galápañeo after more than 20 years living on the islands.

Castrejón was a researcher at Universidad de Las Américas for almost four years before he began his role as an investigator and co-founder at a INNOVAPESCA CIA. LTDA, a Puerto Ayora-based organization that promotes “artisanal tuna fishery development” by diversifying the livelihoods of fishermen.

With more than 50 publications on fisheries in the region, Castrejón says that he is constantly looking for new solutions to remedy the fishing landscape in the Galápagos, even if it means employing a controversial practice like longlining.

To Castrejón, longlining is only one of the solutions to rectify the overexploitation of fish, specifically tuna, employ better tuna fishery reorganization, and transform what he said is an outdated policy. His goal is to create a circular economy that will one day use tuna across sectors in the Galápagos to stimulate economic growth and produce less waste. Community engagement is one area he hopes to do this with, not only to promote tuna consumption but to view it as an economic prospect.

Even as fish dominate as the islands’ second-largest industry, little of the fish caught actually goes to the Galápagos people. The formula of exported fish, over-reliance on imported goods, and a transplant culture devoid of eating fish has created malnutrition in almost one in five children and one in three adults, according to a study. The study found that communicable diseases have a strong link to overweight and underweight individuals due to unhealthy diets and poor water quality.

In publishing his article, “Addressing illegal longlining and ghost fishing in the Galapagos marine reserve: an overview of challenges and potential solutions,” Castrejón not only aims to make longlining realistic through legalization and conservation practices, but also to debunk what he believes to be misconceptions about the practice. One such misconception, he said, is that longlining contributes to ghost fishing. “Ghost fishing” refers to the occurrence of abandoned nets and longlines from illegal operations that drift through ocean waters, indiscriminately killing marine life.

Translation: Standards for mechanisms or reference points should be provided that allow us, as boat operators, to know whether a fishing technique should be permitted, not based on scientific criteria. So that’s not in the fishing regulations. The issue of research is also unclear. Longlines aren’t prohibited, but they aren’t allowed, for example. That is, in a clear manner with clear processes, research is at the discretion of the authorities. So, it’s not something that’s mandatory, but rather it’s at the discretion of the authority in charge. What has often happened is that research isn’t done, it’s not feasible. -Mauricio Castrejón, Ph.D.

Castrejón asserts that inconsistencies between arguments against longlining and what the data suggests make longlining’s prohibition unjustified if there is not sufficient evidence to prove it has any substantial effect on ghost fishing or unintentional shark catches.

Since 2019, Ecuador has introduced tougher penalties on ghostfishing and now openly shares its vessel-tracking data (AIS) for 1,200 fishing boats to improve transparency and accountability within the community, but the phenomenon still continues to create a profound impact.

This, coupled with fisheries struggling to make capacity, he said, makes it difficult for fishermen to pursue fishing as their sole source of income and feed their families in the process.

In order to engage fishermen and the community in his work, he said that the Galápagos needs to create incentives for fishermen to work across different sectors, such as tourism, and start implementing midwater longlining and spearfishing as a way to transition to longlining.

Since longlining’s introduction to the region, sharks have remained the primary species at risk from longlining. However, Castrejón said that his next venture is to research the true impacts of contemporary longlining on sharks in comparison with other causes of death. He also claims that the endemic species the Galápagos is known for are not significantly impacted by longlining either.

Ultimately, he said he hopes that in dismantling the ideas around longlining, he can drive more attention toward outdated policies that he claims are hindering fishermen.

Translation: If we are naturally successful, the other fishermen, possibly according to the fishermen themselves, their perspective is that other fishermen will want to join this initiative or copy it, not on their part, let’s say, and the idea is to train them, right? I mean, the question here is that they realize that by capturing a deep-sea adult tuna with technology, you are going to earn more. And you are going to risk less because you are going to do it legally, right? So what we are looking for is to regulate tuna fishing, but in a way that is sustainable, with techniques, with technology, with innovation, and at the same time, work on the market issue, work on the consumption issue, create a strategic give-and-take with restaurants, with hotels. -Mauricio Castrejón, Ph.D.

When told that researcher Alex Hearn would be the next interview, Castrejón chuckled to himself and said that they have known each other for years, having met during their time at the Charles Darwin Research Center.

But the best of friends can also be their fiercest critics.

Hearn, a professor of Biological and Environmental Sciences at the Universidad San Francisco de Quito with a Ph.D. in marine biology, wrote a commentary in 2024 in response to Castrejón’s article. In it, he criticizes the lack of attention toward malnutrition on the islands and shark populations that could be threatened.

Based in Quito, Ecuador, Hearn lived in the Galápagos for almost seven years starting in 2002, when he led monitoring teams at fisheries as a part of a nonprofit.

For an issue like longlining that has a long, complex history in the archipelago, Hearn believes it is time to turn the islands’ attention toward other social issues exacerbated by the already-vulnerable Galápagos economy, which depends heavily on their reliance on imports rather than on locally sourced products.

A World Bank report from 2018 lists tuna exports from the Galápagos at 118 tons per year, whereas about 8,879 tons of food were imported to the Galápagos in 2017, with that number projected to increase to more than 44,000 tons by 2037, according to a study by Cambridge University Press.

According to Hearn, moving away from an overreliance on imports requires community and interdisciplinary investment that he says is not instilled within Galápagos culture.

Hearn described the culture as “sectorial,” meaning that each industry — whether it be tourism or fishing — will only go so far as to protect their own interests. At the end of the day, if a particular practice does not harm their particular industry, Hearn says they will not care to change.

Hearn says that investing more resources in feeding Galápagueños and growing a culture of fish-based diets, such as in incorporating fish into school food programs, would go farther toward solving the bycatch problem.

Castrejón claims that creating new fisheries will help advance new technologies and local economic independence, but Hearn counters that by saying that creating new fisheries is not going to solve the heart of the issue, which is promoting the tracing of the fish and incentivizing local consumption to tackle the islands’ malnutrition.

With already developed markets and industry investors coming into the Galápagos, both domestic and foreign, and projects that he is promoting and believes has promise, Hearn said that there should be an extra step in sourcing transparency in order to stop inadvertently promoting longline practices.

Although both Castrejón and Hearn will be arguing on this end for the foreseeable future and resistance against illegal longlining will likely continue to come from fisherman and longlining advocates, Hearn shared that he is not worried about longlining being legalized anytime soon in the Galápagos.

As Castrejón and Hearn debate these issues from Ecuador’s capital, those working daily in the fishing industry in the islands have their own thoughts on sustainable fishing and what they have the most to lose or gain in the debate around longlining.

At fewer than 12,700 people, Puerto Ayora is still one of the largest towns in the Galápagos. Buzzing tourists headed to the Charles Darwin Research Center or to the number of locally owned shops that line the streets, but over by the cement ramps leading to sea are the fishermen waiting at their boats.

Walter Borbor, one of said fishermen, was pulling in his boat for the day when I approached him at the docks.

Although not from the Galápagos, Borbor is a fourth-generation fisherman who has spent the past 30 years fishing within the reserve. After noticing changes and impacts from pollution and overfishing, he joined Frente Insular, a citizen-led organization leveraging a fisher’s role in protecting the very things they harvest through technological efforts, conscious fishing loads, and keeping polluters accountable.

Translation: Of course, the resilience we have here is always about conservation, and that’s what drives us. Personally, I have a traceability system, I have cameras. How do I make and show you my sustainable catch? So, how do I fish it? The permitted gear I use, how do I handle it, and how do I sell it? So, sustainable fishing. -Walter Borbor

Borbor sells all of his fish on Santa Cruz island and advocates for locally sourced fish consumption. When it comes to the issue of longlining, he thinks that it is a practice that should stay illegal because it interferes with the conservation efforts he enforces and is not afraid to report those that employ the practice.

Translation: I’m a neutral person who, well as I said, likes to preserve and protect. We know that if you use a banned technique, you get in trouble, so why bother? And another thing is that if I see someone doing it, I can also report them. -Walter Borbor

Christian Saa, a National Park of Galápagos Naturalist and National Geographic Lindblad Expeditions Expedition Leader, introduced me to Borbor at Puerto Ayora and spoke vehemently against longlining as a method that undermines conservation. Like Borbor, he thinks that fishers are at the heart of conservation, reducing overfishing in the islands, and pushing the policy that can save their local industry from foreign threats as well. “I believe that right now, the fishing sector is a good ally of the conservation sector because it’s given its space,” Saa said.

The big problem right now is foreign economic interests, which I would say, are more dangerous than the sectors that operate within the Galápagos. I’m talking about big capital, not even foreign capital, but rather national capital from those in power in Ecuador who want to change the face of the Galápagos to a more developed and less well-preserved place like what we have now. -Christian Saa, translated from the Spanish

Even as Hearn and local fishermen try to squash arguments against longlining, the possibility of its legalization continues to loom from the work of advocates like Castrejón that believe it can be done in a responsible way. Now, as the Ecuadorian government plans to eliminate the agency responsible for environmental protection, there is no telling what direction fishing will take in the coming months.

As Hearn emphasized, however, the focus should begin to divert away from this issue and toward using the fishing industry to combat malnutrition on the islands through school and community programs, such as one that Hearn said is to start on San Cristobal island in late summer. Marine animals and birds are not the only ones that depend on the sea on the Galápagos. As humans continue to exploit it, the question remains: How can we make sure there is an ocean and fish left to enjoy?

Editor’s Note: AI transcription and translation was used in the process of editing this article.

Editor’s Note: Lindblad Expeditions, our Planet Forward Storyfest Competition partner, made this series possible by providing winners with an experiential learning opportunity aboard one of their ships. We thank Lindblad Expeditions for their support of our project.