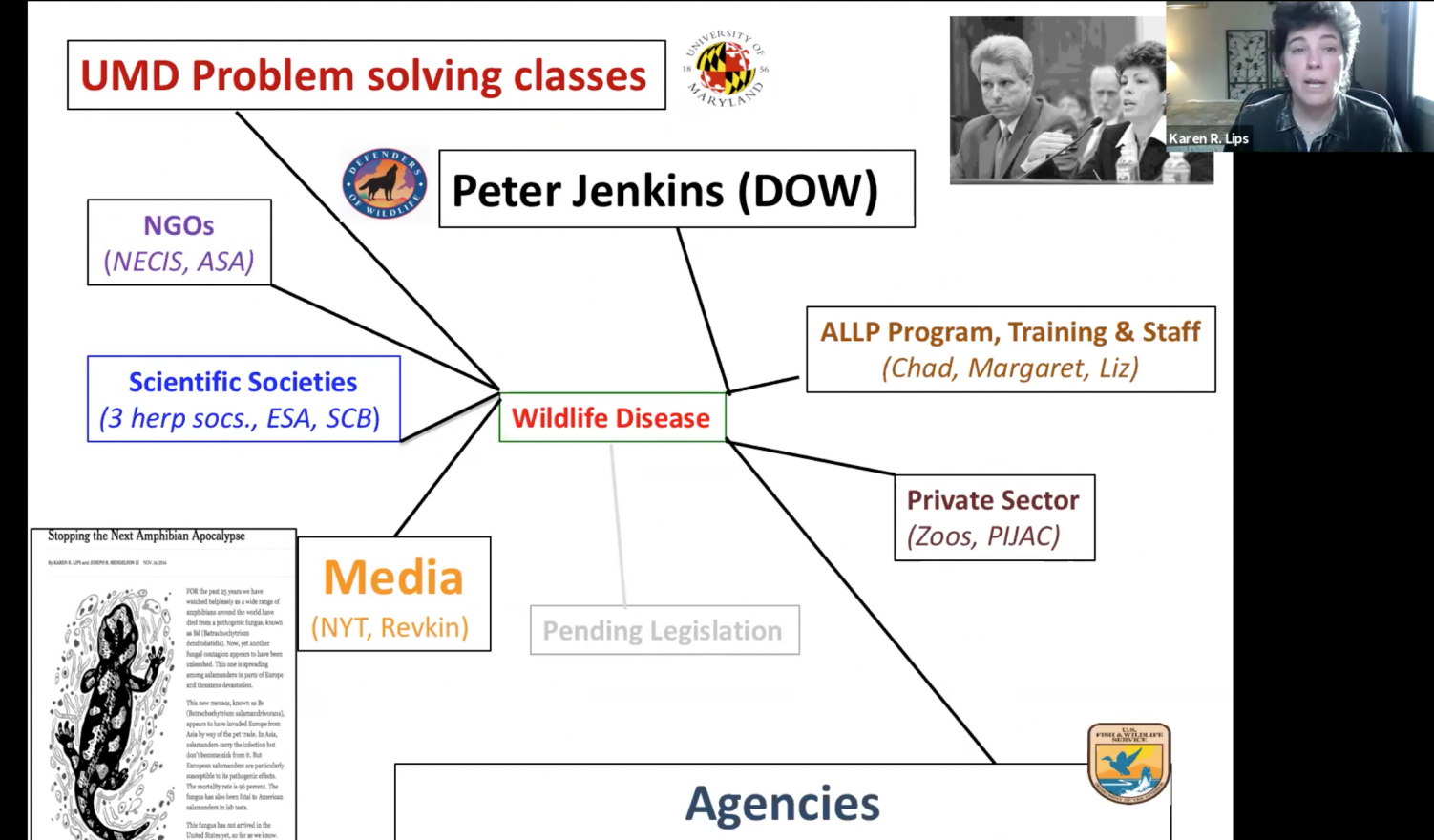

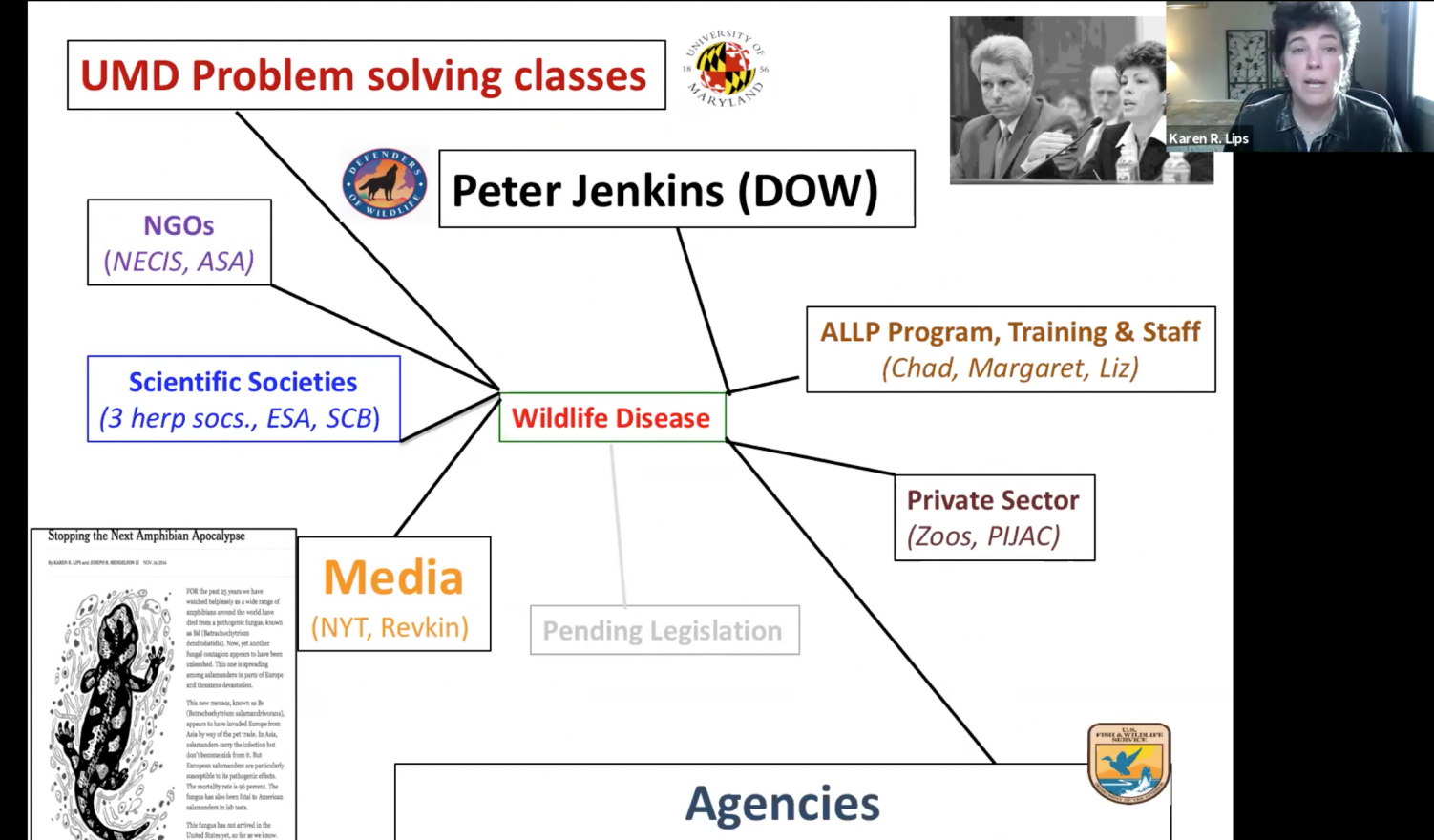

In a Zoom interview, Lips describes how she worked with multiple organizations to create Wildlife Conservation Legislation. (Screengrab from Zoom)

In a Zoom interview, Lips describes how she worked with multiple organizations to create Wildlife Conservation Legislation. (Screengrab from Zoom)

Imagine a disease stealthily traveling around the world, killing millions, and not leaving behind a trace of its existence.

For almost thirty years, Karen Lips has been studying and advocating for policies to stop one mysterious fungal disease that has irreparably damaged international amphibian populations.

At the first World Congress of Herpetology in 1989, scientists compared extinctions of amphibian species in different environments since the 1970s, but they had no idea what was causing these declines.

Lips noticed this same decline as a graduate student in 1992, when she spent a year and a half recording the reproductive season of spiky tree frogs, called Isthmohyla calypsa, in a cloud forest between Costa Rica and Panama.

Lips remembers seeing “from like 200 [frogs] in an hour to two all day.” It was a massacre but without any dead frogs left behind. Now, if you look up the Isthmohyla calypsa frogs, they are considered critically endangered in Panama and extinct in Costa Rica.

Lips remained undeterred by the subject of her studies disappearing over her winter break. She finished her doctorate in tropical biology and began writing about the decline of amphibians in a seemingly pristine habitat.

Like she would prove to be for most of her career, Lips was ahead of the curve. Comparing the earlier extinctions in north Costa Rica to the disappearance of species in the southern cloud forests she’d seen, she noticed that there was a wave of extinction traveling down into Panama. In 1996, she brought a team of grad students with her to western Panama and started recording the amphibian populations, hoping to catch the mysterious disappearance of frogs in its tracks.

Lips and her students finally had a breakthrough when they found 50 dead frogs in one area, all of different species. The researchers sent the frogs to a lab that found something in their skin; a chytrid fungus, called Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd).

Amphibians “breathe” and drink through their skin, it’s how they absorb water and oxygen and dispose of carbon dioxide. When an amphibian’s skin is blocked by Bd, it alters their blood chemistry. Slowly all the organs in a frog’s body will shut down as Bd spreads, and according to Lips, “eventually their heart just gives out.”

Amphibians tested in Australia and at the Smithsonian National Zoo all had the same skin infection. Lips had helped prove that an epidemic was killing amphibians worldwide, not climate change.

For many scientists this discovery would be the end of their work, but as Lips watched Bd directly cause the extinction of 90 species of amphibians and the decline of 500 species, she realized her work must go beyond traditional academic institutions.

“Because she saw her study and research sites destroyed by this disease, she realized she was going to have to jump in and get her hands dirty in the policy world to try to deal with it,” says Peter Jenkins, an environmental lawyer.

Jenkins first partnered with Lips in 2008 to use her Bd research to petition the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to restrict the importing of infected amphibians.

“Fish and Wildlife basically said after a lengthy review, what do you want us to do? Bd is already here,” Lips summarized. “And so they just sort of put it on the shelf.”

In 2014, a new chytrid fungus that affected salamanders and other amphibians was discovered, called Bsal. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reached out to Jenkins and Lips again, and this time they partnered with advocacy groups, journalists, and even the pet industry to help make their case. Lips, with her wide smile and willingness to break down any scientific process into simple terms, spoke at congressional hearings and met one-on-one with senators.

“She’s a really great resource in that way,” Jenkins said. “And is, you know, not only fantastic on the science, but can communicate about the policy.”

Lips partly gained these communication and collaboration skills during her fellowship at the Aldo Leopold Leadership Program, now called The Earth Leadership Program, where program designer Margaret Krebs remembers “her curiosity and her ability to just persist.”

“There is nothing about her that was pompous or ‘listen to me.’ You know, she really was humble,” Krebs said. “She really recognized that it was going to take a whole network of people to move this forward.”

Lips and Jenkins’ collaborative work helped to halt the spread of Bsal coming from Asia and Europe. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service blacklisted the international trade of 200 species of salamanders, leading to Canada and the EU banning imports of all salamanders.

Lips has shown a willingness throughout her career to develop new skills when her research leads to novel fields of ecology and calls for urgent policy change.

“I got into all this because I really wanted to sort of go to the jungle, be the Explorer, live in my shack and do what I was doing,” Lips said. “And then when the frogs started dying, I basically changed. And I ended up as a disease ecologist for you know, a couple decades.”

When Lips was finishing her doctorate, disease ecology wasn’t an established field, and scientists weren’t working with lawyers to successfully petition the government to protect amphibians, but Lips carved out the skills and connections to pursue both paths.

Lips is continuing to re-define her role as a biologist and policy advocate. Now, she’s raising awareness of how human encroachment on wildlife is causing diseases like Bd and COVID-19 to appear.

Lips explained that “it’s not so much about the frogs and salamanders per se. It’s about the broader problem of infectious diseases of wildlife that are completely unregulated.” While COVID-19 can be traced back to human interactions with diseased animals, the spread and variants of Bd are connected to the international trade of amphibians.

“If we can prevent the next COVID, we can also save the frogs at the same time, right?” Lips asked.