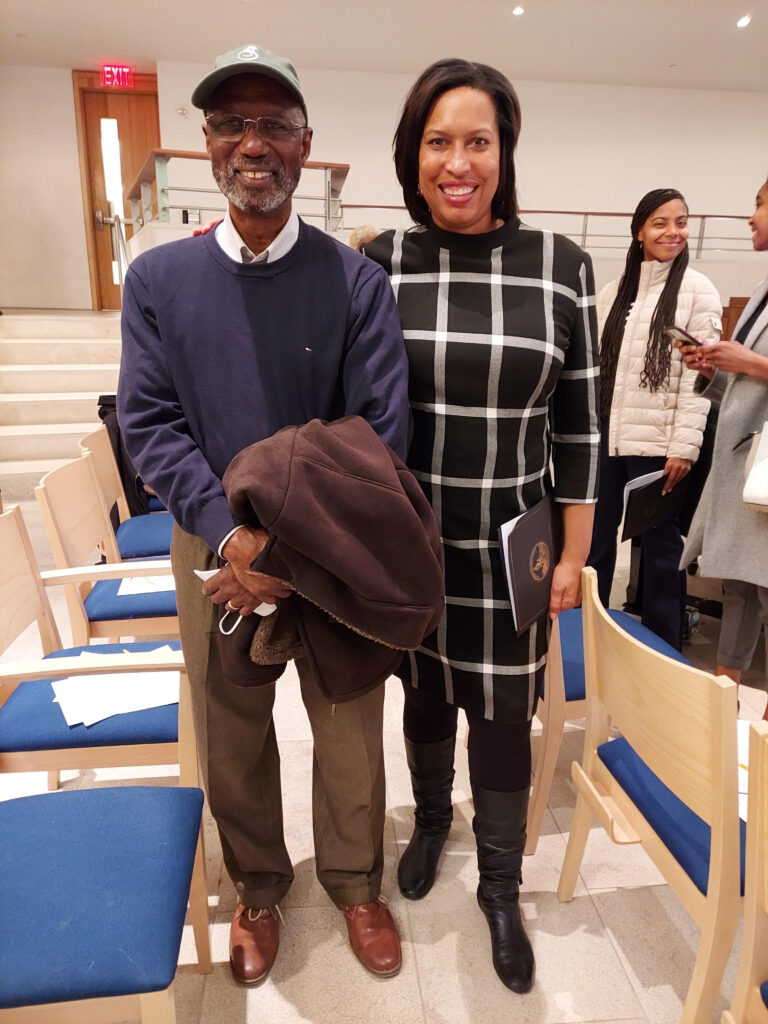

Crosslin Silcott

Crosslin Silcott

Dennis Chestnut first learned how to swim at the mouth of Watts Branch, a tributary that feeds straight into the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C., a river that has become so polluted that it is no longer legal to swim in.

Chestnut is a lifelong resident of Ward 7, located in the northeast quadrant of Washington, D.C. The ward is home to over 74,000 people, and is about 87% Black and 5% white. Additionally, around 20% of families in the ward live below the poverty line.

Chestnut found his passion for environmental justice at a young age and has devoted his life to making his community a sustainable place through new developments, educational programs, and water cleanup efforts.

“This community is what really contributed to why I’m passionate about everything I’m passionate about,” Chestnut said.

In a country where over 50% of rivers and lakes are considered “too polluted” to swim in, cleanup efforts are becoming more important — and more common — than ever before. Despite being named the greenest Ward in Washington by the D.C. Office of Planning, Ward 7 has historically been neglected when it comes to environmental and sustainability efforts.

Chestnut is aiming to change that through extensive research and initiatives that will make the ward, and eventually the entire city of D.C., a more sustainable and safe place to live. He is especially involved in the effort to take the Anacostia off of the list of “unswimmable” rivers.

Chestnut’s commitment to his community and the river continue to inspire others throughout D.C., leading to him being named “Lifetime Champion of the Chesapeake” by the Chesapeake Conservatory.

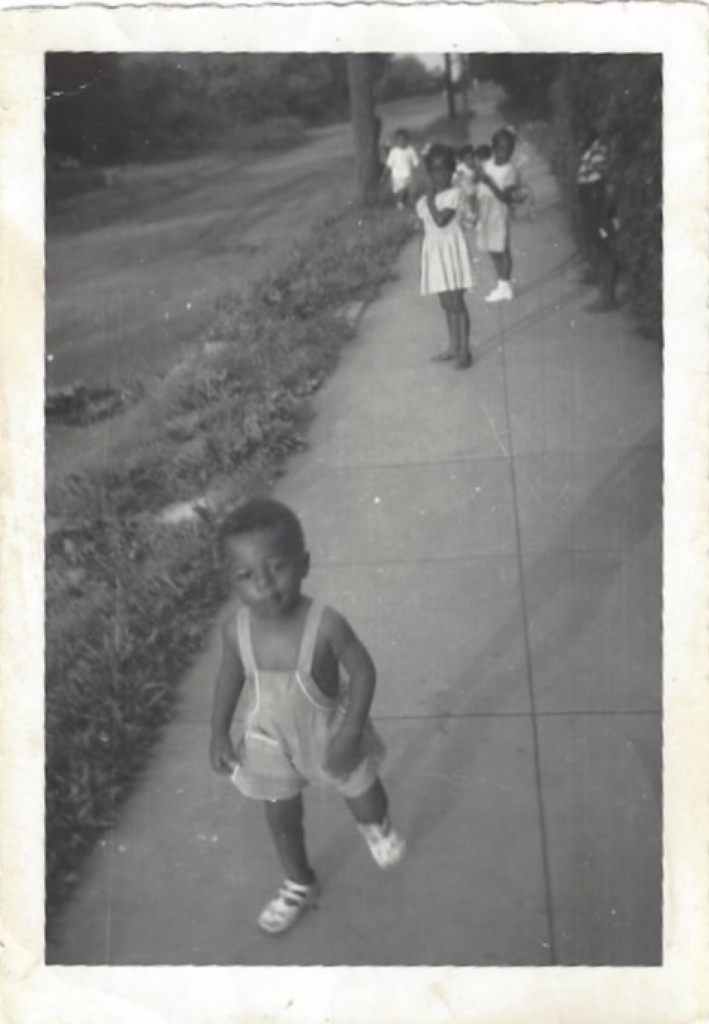

According to Chestnut, besides the occasional episode of the Mickey Mouse Clubhouse that he would watch after school, nothing on the television really interested him as a young boy. Instead, he spent a great deal of time outside with his friends, whether it was interacting with nature in the woods or playing in the stream of Watts Branch.

“It didn’t matter whether it was summer, winter, spring, or fall,” Chestnut said, “we were out there.”

The older kids, who teased and challenged Chestnut and his younger friends to get into the river, had been swimming there long enough to know how to keep everyone safe.

“They would warn us, and it kept us from getting out into the portion of the river where there was current,” Chestnut said. “And they told us why. They say when you get out there, you might not be able to come out of it.”

Although he was able to avoid the dangerous current in his childhood years, Chestnut was eventually swept up by the need to make the river cleaner. His passion for the health of the river mirrored the power of the tide. After so many years of diving in, he has yet to come out of it.

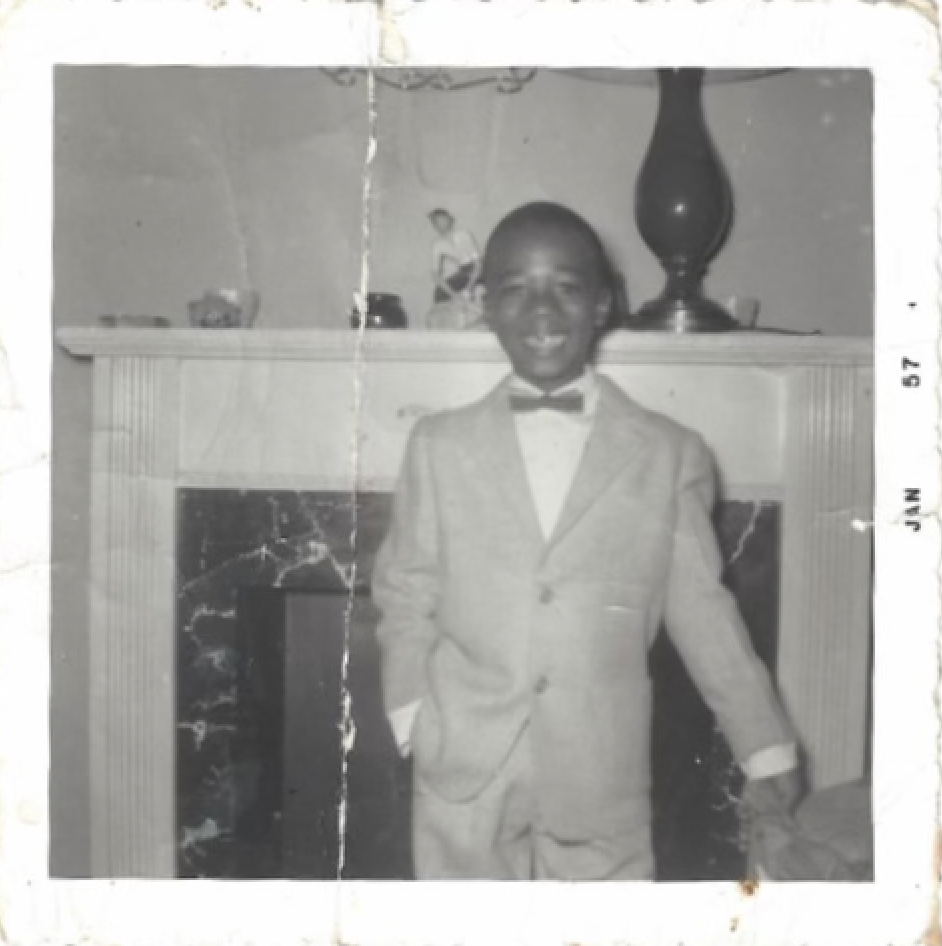

But Chestnut still remembers the days of being a young boy in D.C., swimming in the river with his friends. “We probably had more fun than we would have in the swimming pool,” Chestnut said. At a time when segregation was legal in D.C., Chestnut and his other Black friends were not allowed to swim in the public pools that the white children were spending their time in.

Chestnut said that as a kid, he didn’t really have much of an understanding of what the laws were, besides what he picked up from the occasional television episode or overheard from conversations among his parents and older siblings. He just knew he couldn’t go in the swimming pools, and that they had the river and Watts Branch. And once he started going in, he took every opportunity he got to go back.

“When we got to the river and Watts Branch on hot summer days we probably had more fun than we would have had in the swimming pool,” Chestnut said.

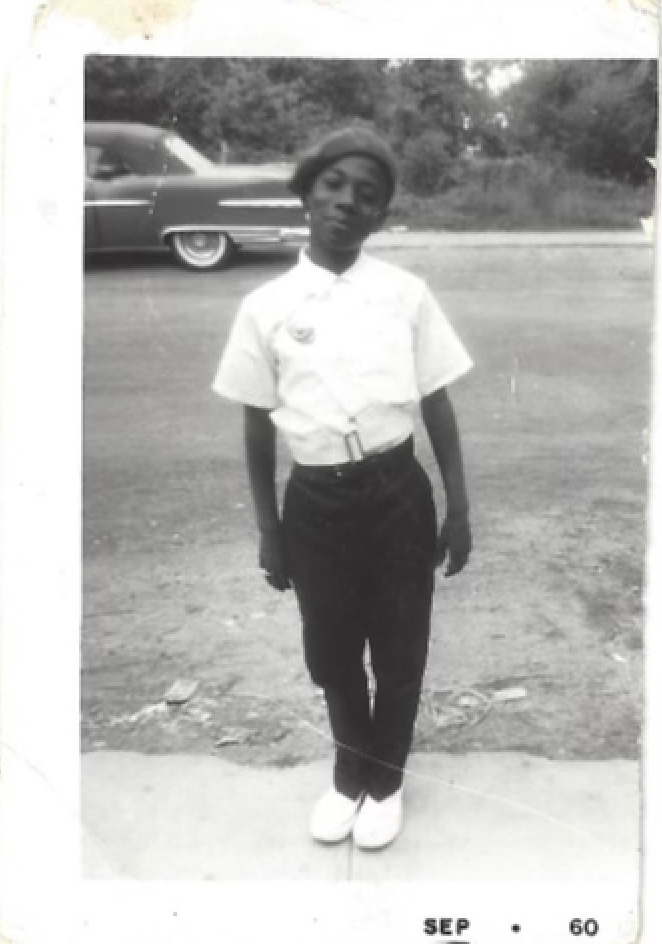

When the legal segregation laws in D.C. were lifted, Chestnut and his Black friends were able to go to their local swimming pools. But it wasn’t long before it became evident that laws being lifted did not change people’s minds.

Chestnut said as soon as him and his Black friends would get into the swimming pool, the white kids would get right out.

“We didn’t really mind though,” Chestnut said. “We’d have the high diving board to ourselves.”

Chestnut’s passion for serving his community and promoting sustainability started at a younger age than he even realized. He remembers being only seven years old and being involved in macroinvertebrate sampling, a scientific method used to assess the health of aquatic ecosystems. Participating in this process allowed him to find and study subaquatic life in the nearby creek, which he said shaped his daily life immensely.

When Chestnut reached junior high, he fell in love with one class in particular — science.

His science teacher Mr. Teasley’s room was covered in aquariums, one of which was empty. When one of his classmates was given permission to bring in wildlife to fill in the empty aquarium, Chestnut teamed up with him to start what he described as “their own little project.” They would catch everything from snakes, to salamanders, to turtles, to frogs, to crayfish.

“We would bring in the things and try to give them as close to their natural environment as possible inside of that aquarium,” Chestnut said.

He described this first “little project” as the foundation for his interest in nature and the outdoors. Chestnut is the youngest child in his family, and was the first to attend college. When he got there, he found yet another class that grabbed his attention, called environmental science. The class talked about the impact of weather and how it worked with the environment.

“[The class] began to put together some of these things that I would relate to as a kid out there,” Chestnut said. “It just kind of put it all into perspective for me.”

In 1980, Chestnut moved back into his childhood home, where he was raised and where he would go on to raise his six children alongside his wife Zandra. Despite being officially retired, he has not stopped his tireless efforts at bettering his community, referring to himself as a “practicing civil ecologist.”

Currently, he is chairing the Ward Seven Resilience Hub Community Coalition, a 501(c)(3) that aims to educate residents about climatic changes, especially floodplains in the area, and recover from disruptions, including chronic stressors and acute emergencies.

According to the Department of Energy and Environment, the resilience hubs that the coalition has been working on building since 2017 are facilities set up in a trusted physical space that help connect residents to resources, build resilience skills, and cultivate relationships throughout the communities. They also increase community engagement through after school programs, events for elders, and job training.

Chestnut also served as the founding executive director of Groundwork Anacostia D.C., a nonprofit organization that partners with developers to create sustainable projects throughout the city.

Marian Dombroski, another member of the community devoted to cleaning up the Anacostia, has worked with Chestnut on several environmental projects for almost 20 years, including water quality monitoring and serving on the Leadership Council for the Cleaner Anacostia River.

“He’s just got this joy that really comes through,” Dombroski said. “Dennis is a gem.”

Dombroski noted Chestnut’s first hand experience in the water, saying that since he used to swim in the river, he really saw it go downhill.

“[His passion for the Anacostia] is from that perspective, just a love of the river and a genuine concern,” Dombroski said.

When asked about his last time in the Anacostia River, Chestnut laughed and reflected on an accidental slip that occurred while cleaning out litter traps in Kenilworth Park that caused him to fully submerge in the river.

“I don’t know what I slipped on but I went right under. Completely under,” Chestnut said.

Although this accident was Chestnut’s most recent swim in the Anacostia, it will definitely not be his last. He fully plans to jump back in this spring for the Anacostia River Splash event.

He has been a long time advocate for getting back into the river, and helped organize and promote the upcoming Anacostia River Splash event, hosted by the Anacostia Riverkeeper organization. The event was originally scheduled for this past summer, but was rescheduled to spring 2024 due to poor weather conditions.

According to Chestnut, Anacostia Riverkeeper and other stakeholders have been monitoring the water quality for years by collecting samples and having them tested and analyzed.

“I was tempted to jump in when we were doing the monitoring because it was a hot day in July and we were getting such good results,” Chestnut said. “If I had my swimming gear, I would’ve done it then.”

Chestnut said he has all the confidence that the water is safe to swim in, and is inviting as many people as he can to the event.

“If you’re available, come on down, check it out. Trust me, it’ll be good enough to jump in,” Chestnut said.

Even though he has to wait a few more months before officially jumping in, Chestnut still visits one of his favorite spots on the river in Kenilworth Park.

To find Chestnut’s special place along the river, one can drive into Kenilworth Park, a former landfill that’s been transformed into a 700 acre park and aquatic garden that stretches throughout the community.

After driving a couple miles into the park and walking a short path through the woods,

Chestnut’s spot comes into view. He originally started going there in the late 1970s to fly kites with his kids.

“There were no electrical lines to compete with the big open spaces. This was our kite flying area,” Chestnut said.

As he watched his children find joy in the same water he once did, Chestnut couldn’t help but notice the changes that had occurred since he was a boy. While there was no trash in the stream when he was younger, some had started to pile up with time.

“That began to get me involved with trying to clean it up,” Chestnut said, “so that it would be a nice place for them to play at least.”

His kids have grown up and stopped flying kites, but Chestnut hasn’t stopped visiting this spot. In the colder months, Chestnut said he usually goes about once a month, but when the temperature starts to warm up, he returns once a week or more.

Chestnut said that he often visits this area early in the morning as the sun rises, when the eagles, egrets, osprey, blue herring, deer, otters, and beavers are out.

“This is a wildlife wonderland,” Chestnut said.

The animals that occupy the area became known as Chestnut’s “pets,” as he would often tell people he had to go to Kenilworth Park to check on them. Chestnut said people would ask, “Pets? You’ve got pets?” to which he would respond, “Yeah, I’ve got eagles. I’m gonna show you when you get over there.”

And sure enough, Chestnut said, when they arrived at the park, there they’d be.

Chestnut continues to devote his time to several causes and projects promoting sustainability in his community, serving on the board of the Friends of Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens, working with the Anacostia Riverkeeper, and more.

He still lives with his wife in his same childhood home, and his family is still able to come together a few times a year. Chestnut still checks on his ‘pets’ no matter the weather, and continues to help monitor water quality so the community can once again rejoice in all the river has to offer.

It turned out that Chestnut’s older friends’ warnings were right. The strength of the tide would sweep him in, and lead him to a lifetime of commitment to the river’s health. “Once you start, you’re pulled in, it doesn’t stop. So here I am.”