Wil Burns speaks at the Negative Emissions Workshop at George Washington University. (Marija Stefanovic/GWU)

Wil Burns speaks at the Negative Emissions Workshop at George Washington University. (Marija Stefanovic/GWU)

Wil Burns, an expert in environmental policy, holds a Ph.D. in International Law from the University of Wales-Cardiff. Burns’ research primarily focuses on climate geoengineering governance — or, the deliberate and large-scale intervention of our climate system with the goal of counteracting climate change, and the policies needed to achieve that goal.

While Burns helped host a workshop for NGOs on Carbon Dioxide Removal/Negative Emissions at The George Washington University, Planet Forward sat down with him to discuss the Paris Climate Agreement and other climate change policies. Read on to see an edited version of our conversation:

Planet Forward: How did you become involved in climate policy research?

Wil Burns: I started off working on the impacts of climate change on small island states, specifically how small island states might either adapt to climate change or how they might use legal mechanisms to try to “press” the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases to reduce their emissions. Then, about 12 years ago, I became interested in climate geoengineering. I had just happened to read an article, [while] on a plane, from USA Today and I thought it was an interesting topic for teaching because it’s a topic that’s an interface of law and science and ethics and technology and politics.

While teaching about this I got excited about doing more research and ultimately, at John Hopkins, Simon Nicholson from American University and I decided that there should be a think tank that would try to ensure that if we do decide to look at climate geoengineering as a society, that we include all of the stakeholders … That was one of the fears we had, so the purpose of these kind of forums are to ensure that other stakeholders like NGOs and the general public — who would be affected by these technologies — are a part of the conversation.

PF: While human ingenuity seems almost endless, do you think it’s harmful to rely solely on technology to confront the challenges that global warming poses?

Burns: Well, I certainly think it’s harmful to rely on technologies that seek to mask the warming that’s associated with emissions. For example, [there is] one kind of geoengineering, which is carbon-dioxide removal. There’s another kind called solar radiation management. The effort there [with the solar radiation management] is to just reduce the amount of incoming sunlight. So if there’s less solar radiation to be trapped by the greenhouse gases, it reduces the warming. But that’s a short term sort of palliative [technique]. And the long term, if emissions continue to rise, it will at some point overwhelm those options. Plus, those options are extremely risky for a number of other reasons. So, I think that type of technological hubris is wrong. I think the kind of technologies we’re looking at have potentially a supplementary role, but in many ways it’s because they have risks [so] they’re not necessarily permanent either. The best thing we need to do is reduce our emissions. But in a lot of cases when you think about reducing emissions through things like renewable energy or energy efficiency methods, there’s certainly a role for technology in that context also. Solar, geothermal, wind power are based on technology also, so there is a role for technology.

PF: How hopeful are you then that geoengineering technology can reduce the worst case scenarios that climate change could produce?

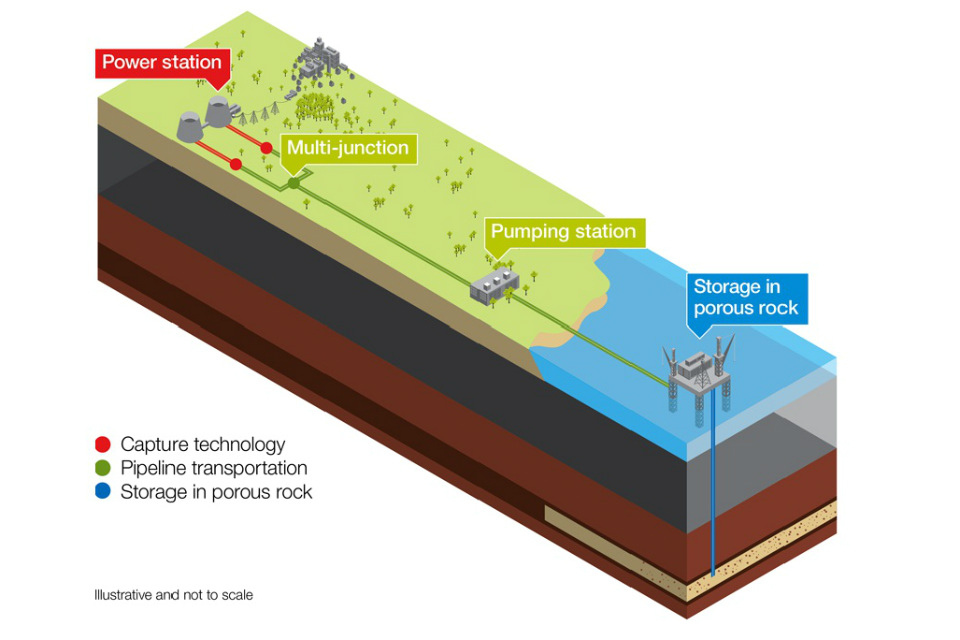

Burns: I think the jury is definitely out. I think that, ultimately, carbon dioxide removal strategies, things like bioenergy and carbon capture (BECCS) or direct air capture will have a modest role to play. But even a modest role is good. The difference between, for example, a temperature increase of 3.0 and 2.5 degrees or 2.5 to 2.0 can be substantial in terms of the impacts on ecosystems or human institutions. Even if the role is relatively modest, which I think it will [be], it could be important. Carbon capture involves trapping the carbon dioxide at its emission source, transporting it to a storage location — usually deep underground — and isolating it. This means we could potentially grab excess CO2 right from the power plant, creating greener energy.

PF: You’ve done a lot of research on the Paris Climate Agreement. What are some steps that countries are currently taking? And do you think the Paris Climate Agreement is effective?

Burns: Well, again, the jury is going to be out on the Paris until we start seeing whether the pledges that are made are implemented, first of all. Then when the parties reassess their claims they have a process called “stock-taking” where they’re supposed to say: Are we on path to meet this goal to holding temperatures well below 2.0° Celsius and if we’re not are we willing to escalate what we’re willing to do? The good news about Paris is that we’re clearly bending the temperature increase trajectory. We used to talk about maybe 4.0° or 5.0° Celsius of increased temperatures by the end of the century. We’re increasingly talking about somewhere between 2.7° to 3.5°/3.7°, so that’s the good news. The bad news is that’s still way beyond where we want to be and way beyond Paris says we’re going to be. If the current pledges of Paris are all totally implemented faithfully, we go from 47 gigatons of carbon-dioxide annually to 58. So we slow down the rate of increase but we keep increasing. We can’t do that because if you think of it as water in a bathtub, the water is going up more slowly but eventually the bathtub will overfill. So the real test for Paris is going to be: when we start these assessments and we realize we’re not where we need to be, are parties willing to escalate? One of the hopes you have with an agreement like Paris is, [it’s] an international agreement in which countries come together, start to learn from each other, start to collaborate more because treaties can foster cooperation. And you hope by doing that parties start to learn that reducing emissions can be done more cheaply than they thought, they realize other countries are actually complying with what they said, and that impels them to do more also, and ultimately reduces emissions more than they have.

PF: The Trump administration has decided they will be pulling the U.S. out of Paris. How complicated is it to pull out of the Paris Climate Agreement? And if we successfully do pull out, how complicated will it be for a following administration to put the United States back into the agreement?

Burns: In terms of the first question, it’s complicated to get out. One of the reasons that we do that is we don’t want other countries that have relied on an agreement and then other parties that have joined just suddenly pulling out because they then have to respond themselves and decide if they’re going to withdraw or if it’s going to change the nature of their commitments. So we make it a slow process. The way Paris works is, you can’t give notice of your intention to withdraw, until three years after you ratified Paris. So we couldn’t give notice that we actually intended to withdraw from Paris until three years from November, 2016. Then it takes another year before it takes effect and goes into force. Since the Trump administration has announced its intention to withdraw, it can’t legally actually announce that intention until three years from November of last year, and can’t withdraw until a year after that. Our effective date of withdrawing from Paris is pretty much after the next election.

PF: So we could possibly have a new administration in office by that time?

Burns: We could. If we announce in three years [after ratification] that we’re withdrawing, it will probably happen and it’d be very difficult to reverse it at that point. Now getting back in, is potentially a relatively simple process in the sense that, what we did with the Paris agreement is we entered by something called an “executive agreement,” instead of going to the Senate. The reason we were able to get the treaty bypassed from ratification by two thirds of the Senate, is because we said we could do this under executive agreement. And we could do this because the commitments we made under Paris were no more than what we were already doing in terms of national legislation or regulations or current treaty obligations. So the argument we made was, since Paris is voluntary, we had already agreed under the Framework Convention on Climate Change (which we’re a party to), that we would reduce our emissions to a level that wouldn’t cause dangerous anthropogenic impacts. We said that Paris just defines what “dangerous” is. We aren’t required to do more than what we were before and we had domestic regulations called the Clean Power Plan to reduce our emissions, and those commitments would be tracked by what we were committing to under Paris. So if we did that again, and we came back in under an executive agreement, it could be done relatively quickly.

PF: If the United States were to implement policies such as a cap-and-trade system, how would that significantly reduce our risks to climate change?

Burns: Well, it depends. If you were to implement either a cap-and-trade system, or a carbon tax or a command-and-control system (reducing emissions by a fixed amount), the key is how much you decide to reduce your emissions. That’s the first question. One of the things we’ve seen under a lot of cap-and-trade programs in the world is that the cap hasn’t been set low enough to reduce emissions that much or put a price on carbon that drives the trading. So that’s a political commitment. The second problem is that even though the United States is a major emitter of greenhouse gas emissions, the bottom line is that we are only one emitter. We’re about 16% of the world’s emissions. So even if we were to massively reduce our emissions, it wouldn’t bring down our temperature trajectory that much. One thing that would be very important is, it would have some impact because we’re a major emitter, but perhaps more importantly it would signal to other countries that the largest economy in the world had the resolve to do it. A lot of other countries in the world compete with the United States… so other countries would be willing to do more because they [wouldn’t want to] be put at a competitive disadvantage in terms [of their] industry.

PF: What are some policies we could implement on a global scale that could greatly reduce the risks of climate change?

Burns: I think one thing we could do that could make a very large difference is to eliminate subsidies to fossil fuels development. We spend hundreds of billions of dollars “incentivizing” fossil fuel production and there’s no reason to provide incentives most of the time. There’s enough profit being made that countries would do it anyway. What it does is it eliminates the level playing field for fossil fuels and alternatives. We subsidize in a lot of countries’ renewables also, but at a much lower level. We’re privileging fossil fuels at a time when we keep saying: renewable energy should compete in the open marketplace. But we don’t have a free and open marketplace. So eliminating those hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies and creating more of a level playing field would really help. We also need to substantially increase our research and development for potential technological breakthroughs in terms of energy. One of the things we know is that the stone age didn’t end because we ran out of stone. It [ended] because there were massive improvements based on technological breakthroughs. The same thing could be said here. If we put more funding into renewables for example, their cost could probably come down so much that we wouldn’t have the political battles that we have now because it’d become simply a question of economic imperative to shift away from fossil fuels. We’ve seen the cost curves for renewables drop dramatically to the point they’re at parity, or lower than fossil fuels. If we were to spend more on research and development, there [are] probably a lot more breakthroughs that would help make that transition more quickly.