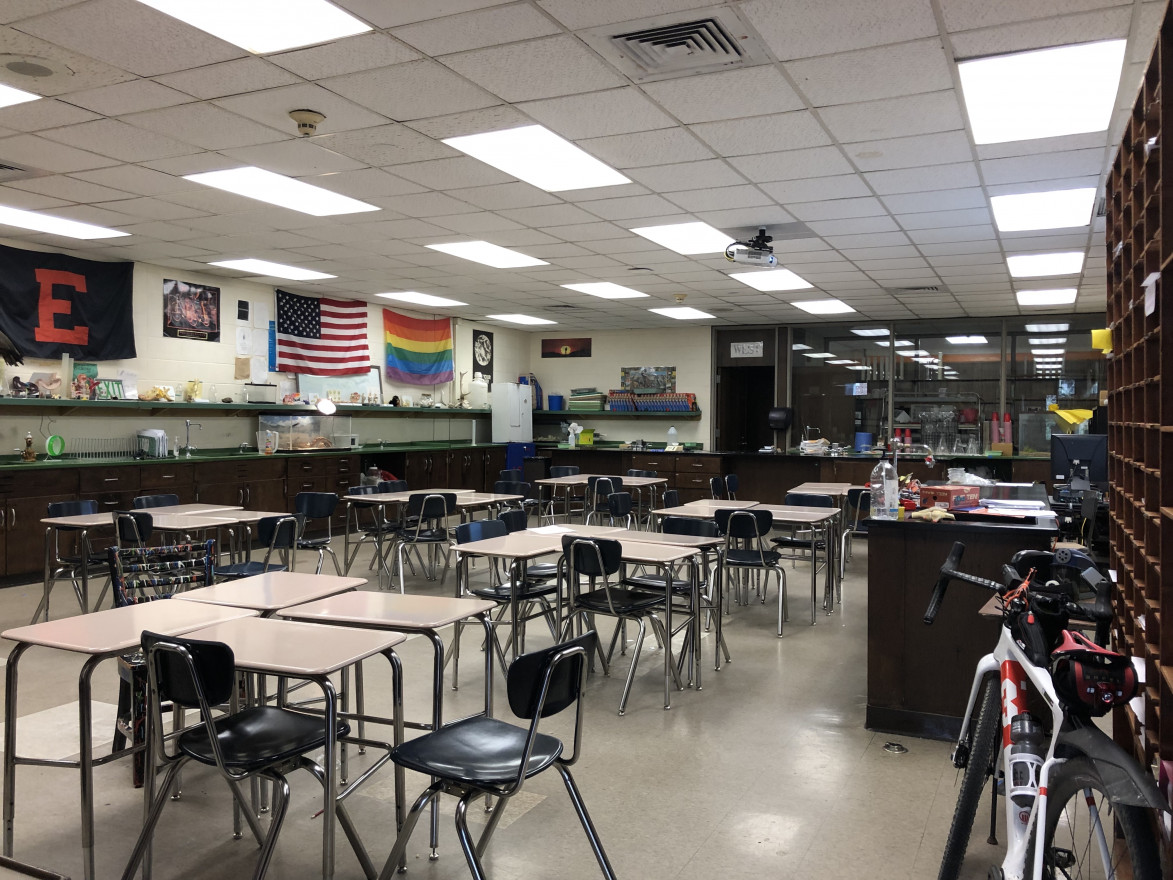

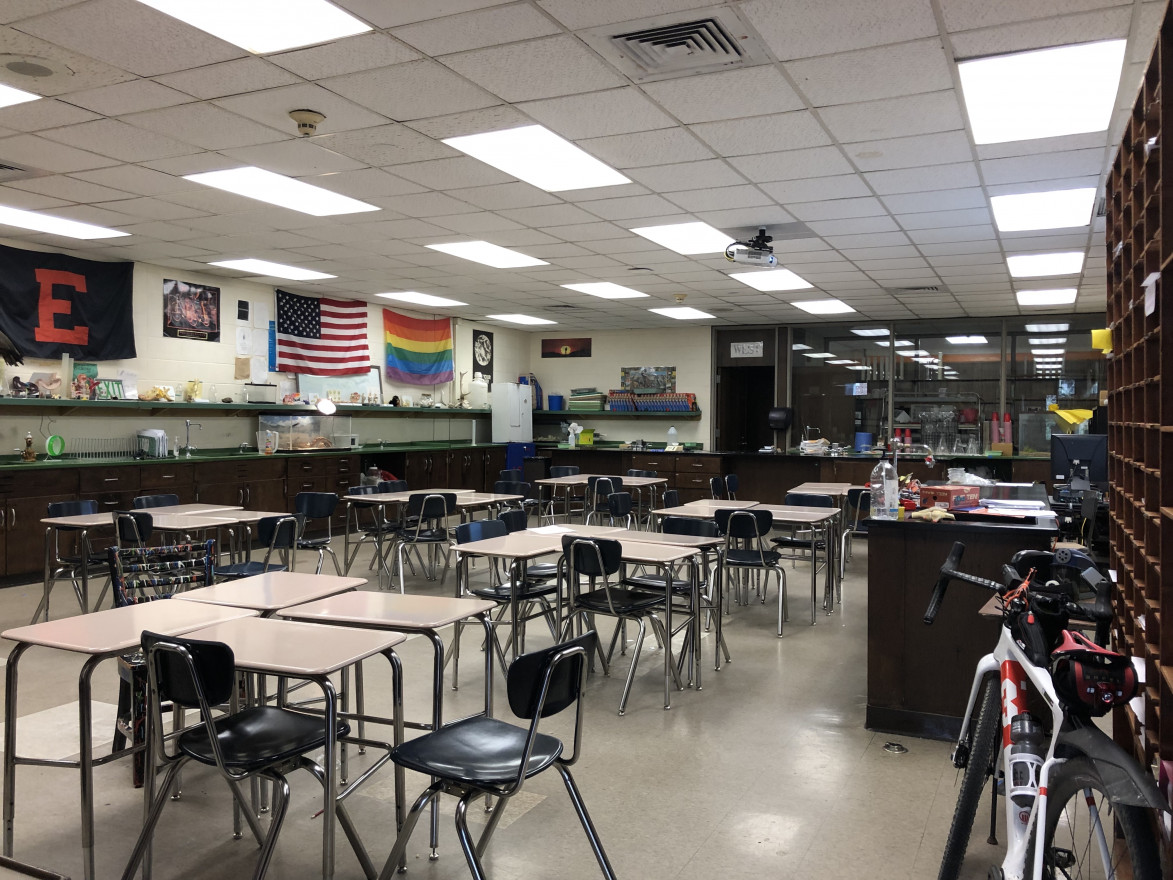

A science classroom in Evanston Township High School where Marla Isaacs, a biology teacher, encourages respectful conversations when teaching about climate change, no matter what their opinion is. (Natalie Chun/Northwestern University)

A science classroom in Evanston Township High School where Marla Isaacs, a biology teacher, encourages respectful conversations when teaching about climate change, no matter what their opinion is. (Natalie Chun/Northwestern University)

Last year, the science department at Neuqua Valley High School in Naperville, Illinois, received a donation of books titled “Why Scientists Disagree About Global Warming” that disputed the existence of climate change. The donation was part of an unsuccessful initiative by The Heartland Institute, a right-leaning think tank based in Chicago suburb Arlington Heights, to distribute these books to every public school science teacher in the nation.

Despite increased awareness and concern surrounding climate change, a recent study from the Pew Research Center shows that the issue remains highly divisive and political. Ninety-four percent of Democrats and left-leaning independents consider climate change a major threat to the nation while only 19% of conservative Republicans believe the same.

Though Naperville is a rather conservative city, most of the teachers at Neuqua Valley ended up using the donated books as doorstops, according to Rhonda Stibbe, a biology and horticulture teacher there.

While this incident proves that there are climate change deniers in the area, Stibbe has not seen that in the classroom. She acknowledged that there might be things that students have heard at home or seen on social media but said that her students are actually very excited to learn about climate change.

“When you put the information in their hands, I think they can reason it out,” Stibbe said. “This generation is very, very visual. There’s a lot of data out there, there’s a lot of maps, there’s a lot of things that you can see.”

Students’ receptiveness to learning about climate change in areas such as Naperville may simply be explained by a generational difference but could also be attributed to a change in political climate.

Anna Kraftson, a biology teacher and learning support coach at Naperville North High School, said that the political alignment has shifted dramatically since she first moved to the area around 15 years ago. Though she initially thought it was conservative and religious, she now finds it to be rather moderate.

“I first started teaching a couple decades ago,” Kraftson said. “Kids were like, ‘I don’t believe in evolution.’”

In a study from the Pew Research Center in 2007, 51% of Americans said that humans have evolved over time. That number has since increased significantly and is up to 81% as of their study earlier this year.

Kraftson has seen drastic changes in students’ receptiveness to evolution, and now finds little problem teaching the subject. However, she said that she faces similar frustration toward the idea of “believing” in climate change.

“It’s just a statement,” Kraftson said. “There’s data. It’s not like ‘I believe in this’ or ‘I don’t believe in this.’ It’s more like, ‘This is the evidence.’”

Paul Vandersteen, an environmental science teacher at Neuqua Valley High School, has experienced similar issues when teaching evolution and has tried to approach climate change in the same way. He said his responsibility as a science teacher is to present his students with evidence and allow them to make their own conclusions.

“I think it’s important that teachers address what science is before they venture into climate change,” Vandersteen said. “You take down the defenses when you present to them the nature of science. And once you present the nature of science, there really is no defense.”

While teachers in more conservative areas must find specific tools and approaches for teaching climate change, they don’t always have too much time to employ them.

According to biology and environmental science teachers at Naperville North, Neuqua Valley, and Wheaton North high schools, climate change is built into the curriculum. However, according to five teachers we interviewed from those schools, the time spent on climate change varied between just two and three weeks, almost a quarter of the time Evanston Township High School teachers spend on the subject on average.

Vandersteen said that he teaches climate change for five to six class periods, around two weeks, in his AP Environmental Science class. He said he spends enough time on the subject.

“I have adequate time to do it justice,” Vandersteen said. “Any more time and I think they might get bored with it.”

While Vandersteen fears his students will get bored after a few days, some biology teachers at Evanston Township High School, located in the neighboring liberal district of Cook County, say they spend weeks to months of the year teaching climate change in their introductory biology courses.

The County Board is currently controlled by the Democratic Party with a 15 to two margin.

Adriane Slaton, a biology teacher at Evanston Township, spends roughly 12 weeks on climate change with her freshman and sophomore students. For their final project, her students take statements that deny climate change and refute them with scientific evidence. Many of her students become rather passionate about climate change after this unit and some have even become vegetarians as a result, Slaton said.

“I thought this was a really important subject to talk about and make sure that students could argue against climate change denial using evidence and reasoning,” Slaton said. “It’s been kind of cool to see what their personal changes have been and the personal decisions that they start to shift when they are realizing that they themselves can do something.”

While Slaton and many other teachers at Evanston Township do choose to put so much time and care into teaching climate change, there really isn’t a curriculum for it, Slaton said. Instead, the time spent on climate change is up to each individual teacher. According to Slaton, there are still a few biology teachers at Evanston Township who don’t teach climate change at all.

“Biology is growing exponentially,” Slaton said. “So there’s always something important, another important topic to still address. If I had my way, biology would be three years or four years long, and then maybe we would start hitting (climate change).”

Evanston Township Science Department Chair Terri Sowa-Imbo said their commitment to teaching climate change is not about political alignment, but a growing urgency.

“It’s something that everyone needs to know, they need to be able to decipher real news and data from fake news and data. And it’s — there’s a lot of that out there,” Sowa-Imbo said.