Cate Twining-Ward

Cate Twining-Ward

We are in a planetary emergency. All high income countries today are massively overshooting planetary boundaries, destroying the living world, and in doing so, restraining the prospects of lower income countries of catching up.

The most recent IPCC report affirms with very high confidence that our window of opportunity to secure a livable and sustainable future for all is rapidly closing. Solutions of scale and speed are in high demand.

However, not all solutions are made equal. Climate mitigation efforts have often hindered local development and burdened low-income communities. It’s well established that communities living in extreme poverty are the most vulnerable to climate hazards, while also having contributed the least to historical emissions. Truly sustainable mitigation plans must therefore include realistic development pathways for low- and middle-income countries.

Scientists are certain that global temperatures will now overshoot 1.5 degrees of warming, triggering irreversible damage. With the current commitments, the IPCC has predicted there will be 3.2 degrees of warming by 2100. There is a mere 5% chance that the earth will stay below 2 degrees of warming.

The planet is desperate for an improved climate policy toolkit.

Recently, a new policy focused on financial incentives, has been published, providing reason for hope. The Global Carbon Reward (GCR), proposed by Dr. Delton Chen, and described in Kim Stanly Robinson’s acclaimed climate fiction novel A Ministry for the Future, aims to incentivize individuals, companies and governments to significantly reduce their carbon emissions through a rewards based system.

The ambitious scheme proposes using a monetary policy to achieve the goals of the Paris Accords, reduce the climate finance gap and incentivize direct industry change. Unlike fiscal policies, which are managed by individual governments, monetary policies are managed collectively by the world’s central banks, who have the resources and flexibility to address socio-economic problems.

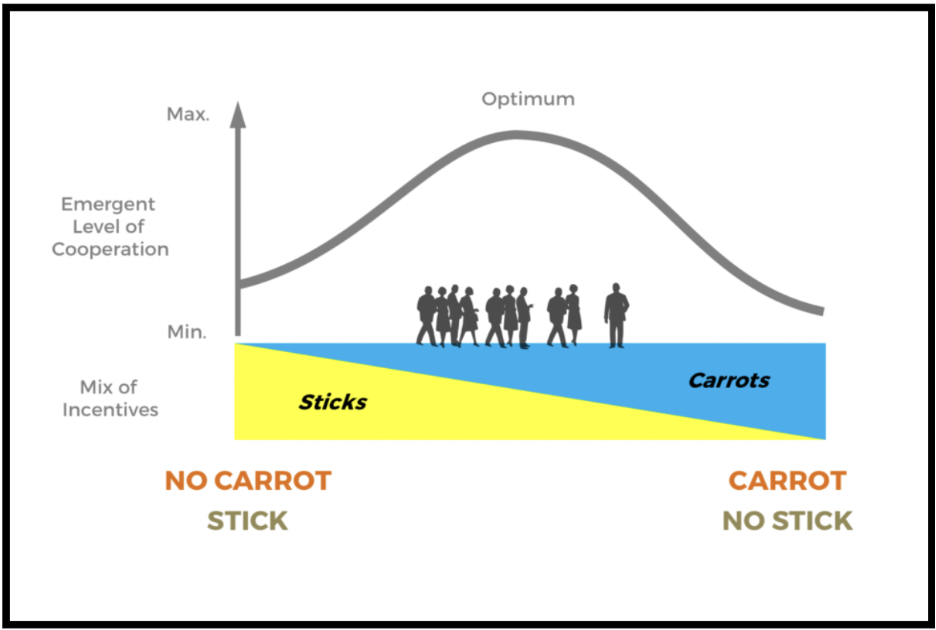

Current carbon policies most commonly use a “stick” approach – they punish emitters for their carbon footprints. The GCR policy instead suggests a “carrot” strategy – one that rewards people when they decarbonize.

Economic strategies that penalize companies through carbon taxes, carbon offsets and cap-and-trade are still needed, Dr. Chen says. But for maximum cooperation and efficiency, his team believes current schemes cannot work alone.

The currency or reward will be given to applicants as a conditional grant, and only after greenhouse gas mitigation activities are measured, reported, and verified, will applicants receive monetary value.

The policy also proposes a new international institution for verifying emissions, referred to as the Carbon Exchange Authority. The authority is described as playing a key coordinating role by managing all aspects of the carbon currency, in collaboration with the world’s central banks. The central banks will underwrite the value of the currency via a public finance guarantee – to insure participants of its economic value in the global market. Between the Carbon Exchange Authority and central banks, the authors of the GCR Policy insist that the new currency will not create any direct costs for citizens, businesses, or governments – as it will be debt-free.

Concerns of efficacy are common among carbon reduction plans. Carbon offset programs are rife with greenwashing and recent literature demonstrates that often offset credits do not actually represent carbon reductions. To address these challenges, the GCR Policy team aims to demystify carbon misinformation and serve as a role model for transparent and ethical emission monitoring. Recipients of the reward must agree and abide by long-term mitigation reporting, to ensure true carbon reduction.

Importantly, authors of the policy wish to create a global scenario in which the most polluting industries – those critical to achieving global net-zero on time – are incentivized to decarbonize now.

By incentivizing industries who pollute the most, such as the agricultural sector, the policy aims to decarbonize all major offenders without compromising their profits. As an example, if a farm were to transition from fossil fuels to on-farm renewable energy, this switch would be rewarded under the GCR policy, potentially both covering the costs of the transition and generating extra revenue for the farm.

Decarbonization will require unprecedented cooperation across all levels of society. This new proposal indicates that the future of innovative climate schemes is forthcoming – some of which are likely to provide scalable solutions for our catastrophic carbon challenges. However, one policy alone will not solve the climate crisis.

Evidently, we need more policies like the Global Carbon Reward: ones that provide innovative roadmaps for rapid decarbonization—without coming at the expense of low-income countries.

What to read more about the Global Carbon Reward policy? Click here to download.