Tanvi Taparia

Tanvi Taparia

By Grace Marie Finnell-Gudwien

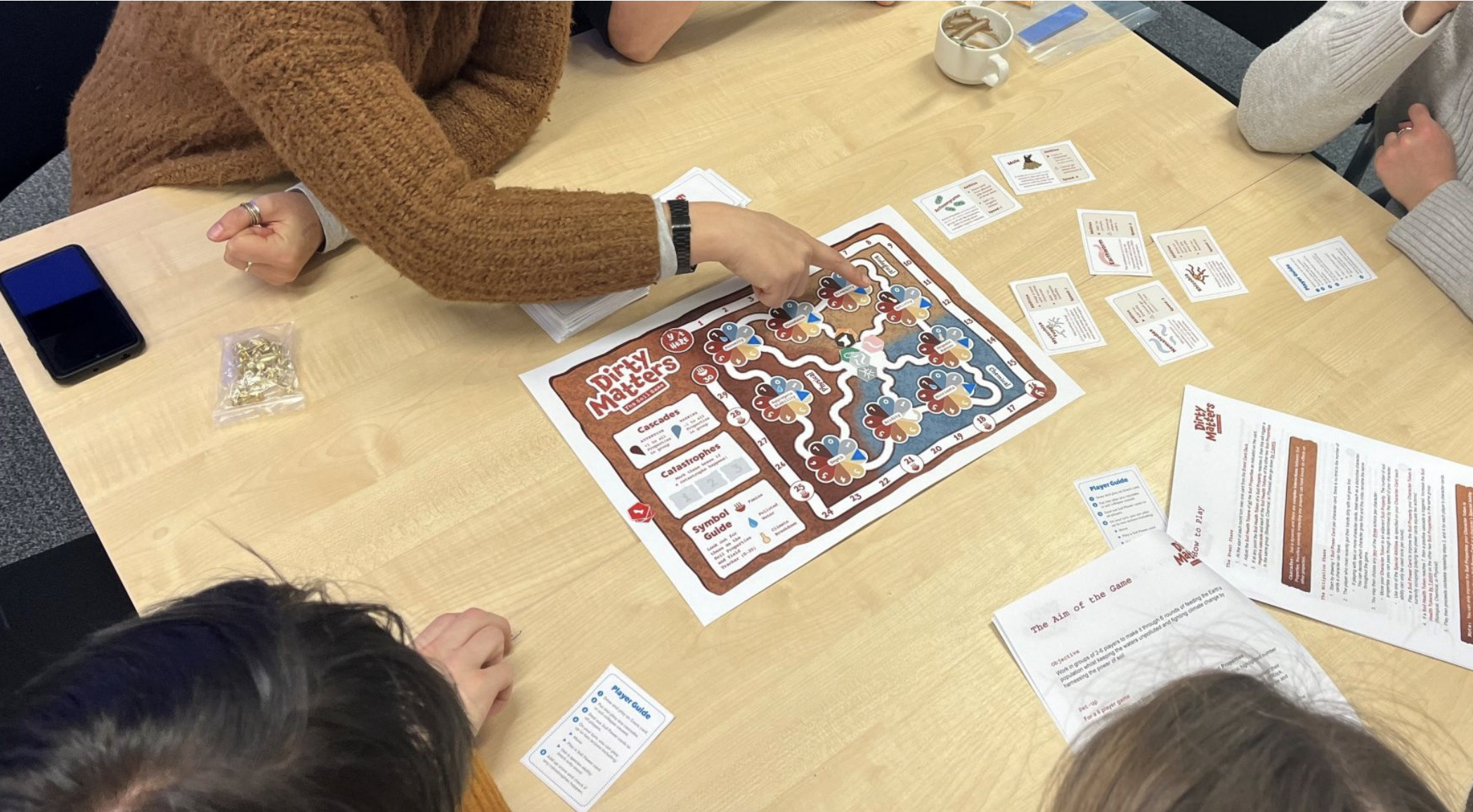

It’s board game night. You’re sitting around a table with some of your friends, ready to play the colorful board game laid out in front of you. You all pick your characters and deal out the power cards to help you enhance properties. You then draw your first event cards to start the action.

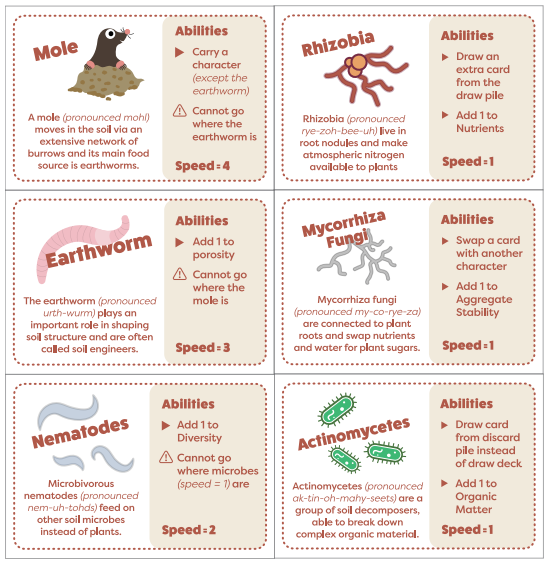

But you’re not playing Monopoly. Your character? Earthworm – you name him Wormy. Your power? Tunneling – Wormy’s specialty. The properties? Porosity, acidity and diversity – Wormy digs in on all that. Your event card? Climate Change – one of Wormy’s arch enemies.

You’re playing Dirty Matters, a free, printable board game created by scientists to teach others about soil health.

“The original idea came from Christina and I during lunch breaks because we both played board games,” said Emma “Bea” Burak, a postdoctoral researcher in sustainable fertilizer management who works at Cranfield University. Christina van Midden is a soil biologist at Cranfield University. The scientists wanted to create a way to engage others in soil science and show why protecting soil is important.

Taking their idea, Burak and van Midden met with Nicolas Beriot, a soil physics and land management research associate at Wageningen University; Tanvi Taparia, a soil biologist microbiologist at the University of Copenhagen; and Michael Lӧbmann, the research coordinator at Svensk Kolinlagring, a Swedish company that works with soil carbon storage. At an online international conference, the group learned about a grant offered by the British Society of Soil Science for scientists to promote ways to help achieve the United Nations’s Sustainable Development Goals. Two days later, they submitted their grant proposal, Beriot said. The group received the 5,000-euro grant.

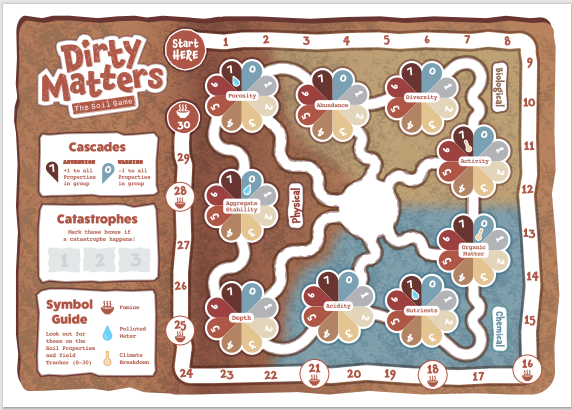

Coming from a variety of backgrounds related to soil science, the group decided to create two board games. Dirty Matters, the first one, which was led by Burak and van Midden, focuses on the micro and macro organisms that contribute to soil sustainability and how they impact the soil’s biological, physical, and chemical properties. It is designed for two to six players ages 8 and older and takes about 40 minutes to an hour to play, according to the game’s website.

“Most people see soil and it’s just like, ‘Oh, it’s just dirt gets under your nails, it makes clothes dirty, plants grow in it or whatever,’” Burak said, “but it’s actually really, really complicated and (an) intricate system.”

To design the game, the group considered how different aspects of soil health interact with each other and read “more literature than what I wanted to read,” said van Midden.

“We were tying it in with these U.N. Sustainable Development Goals,” van Midden said. “It’s looking at how could we manage soil in order to meet these goals.” The group portrays these management practices, such as using cover crops and no-till farming, through Soil Power cards. These cards give players the chance to undo Event cards that harm the soil, such as erosion and drought. Players win the game by managing healthy soil as a team.

The group’s second game is spearheaded by Beriot, Taparia, and Loebmann who wanted to bring to light the social, economic and political aspects of soil health and sustainable development. Taparia said this second game, SOS (Save Our Soils), is not out yet, but will require players to work together to survive on a remote island in a futuristic world facing severe environmental breakdown. In this game, soil and survival go hand-in-hand with cooperative action.

The board games engage the public in learning and using solutions to win a bigger challenge – climate change.

Similarly, scientists are using art to engage people with environmental issues. Sarah Rosengard, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Liberal Arts department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago has been using art to promote science worldwide.

For her PhD in Chemical Oceanography, Rosengard studied the Amazon River. After earning her degree, she stayed in Brazil and worked with a school in Arapixuna, a town in the Amazon River Basin. There, she taught elementary and middle school children about the Amazon River and held a workshop where the kids created art about what the river meant to them, drawing and painting landscapes of the river they see daily. In an interview with Science World, Rosengard said she was surprised that most of the students colored the river brown instead of blue; it showed how perspectives of water and ecosystems vary around the world, and that art can bring awareness to these multiple perspectives. Rosengard put the children’s artworks up as an exhibit in Arapixuna, and she also sent the exhibit to Science World, a science museum in Vancouver, Canada, where Rosengard lived at the time.

“The exhibit in Canada was cool,” Rosengard said. “It was a way to show (the children’s) window into the Amazon to non-Brazilians, the people that were from so far away… that really got me thinking about art, not only as a mode of communication, but as a tool for communities to share the knowledge that they certainly have about the environment.”

Now, Rosengard is teaching Earth science courses to art-focused students at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her courses focus on how students can use their art to help with the scientific process. She started teaching in 2021, when COVID required professors to teach remotely, which forced her to be creative with her curriculum on water science.

Taking these ideas, Rosengard helped curate a professional art exhibit at the American Geophysical Union conference in Chicago last year. Unlike the children’s art in Brazil, Rosengard said, this exhibit showed scientists how art can be impactful. It reminded scientists why they do science in the first place – to answer questions that will help address injustice, such as pollution and climate change-related issues. Science is all about curiosity, Rosengard said, and she said she thinks this exhibit taught scientists how art can show the universal importance of environmental topics and “curiosities of science.”

“I realized that there was an opportunity for art students to use their creative sides of their brain to not only do the science but design the methodology that goes behind it,” Rosengard said. She emphasized citizen science in the course, encouraging students to create pieces that could help study water, such as a goose-shaped sculpture that filters microplastics, a device made of everyday objects to measure turbidity, and an eel-shaped filter made of a nylon stocking. All of these were inspired by work from other scholars, Rosengard said.

Rosengard said she hopes projects like these will inspire more people to see science as something they have the power and ability to be involved in. “I guess I’m looking towards art as a way of expanding the capabilities of science,” Rosengard said. “I’m looking towards art as a way to make science more accessible.”

The creators of Dirty Matters agree. Anyone with internet access can download and print the free game. “This was one of the main things that we wanted to do for the very, very beginning,” Burak said. “All five of us agreed that for any game we produce for educational purposes, we don’t want it to be behind a paywall.”

“Everyday, everyone is making decisions on what they put in the groceries, or how they vote for parties, what kind of news they watch, what topic they discuss,” Beriot said, “and we think that the environment outside, it’s underrepresented in all of this.”

Through engaging, unique ways of teaching science, more people can learn and get involved, one win at a time.