A society for the birds

Those lucky enough to spot a scarlet macaw in the wild will likely just see a flash of crimson, coupled with a sharp squawk from the sky. But up close, macaws are big, boisterous, blaring birds, painted with rainbow colors all over. Each feather is as detailed as a Monet masterpiece, though their own taste is a bit less sophisticated. Said to have the intelligence of three-year-old humans, macaws have a personality to match, alternating between endearingly mischievous, dangerously enraged, and adorably shy. They’re also dedicated partners and parents who mate for life and raise chicks every year—if poachers don’t snatch them away first.

Scarlet macaws are a species of long-tailed, large-beaked parrots, a poster child of tropical birds. Yet in much of their range, including Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize, poachers illegally steal chicks by cutting down nesting trees, which decimates current population and eliminates already-rare cavity nests. Compounded with deforestation, it seems even more likely that extinction will claim scarlet macaws next.

***

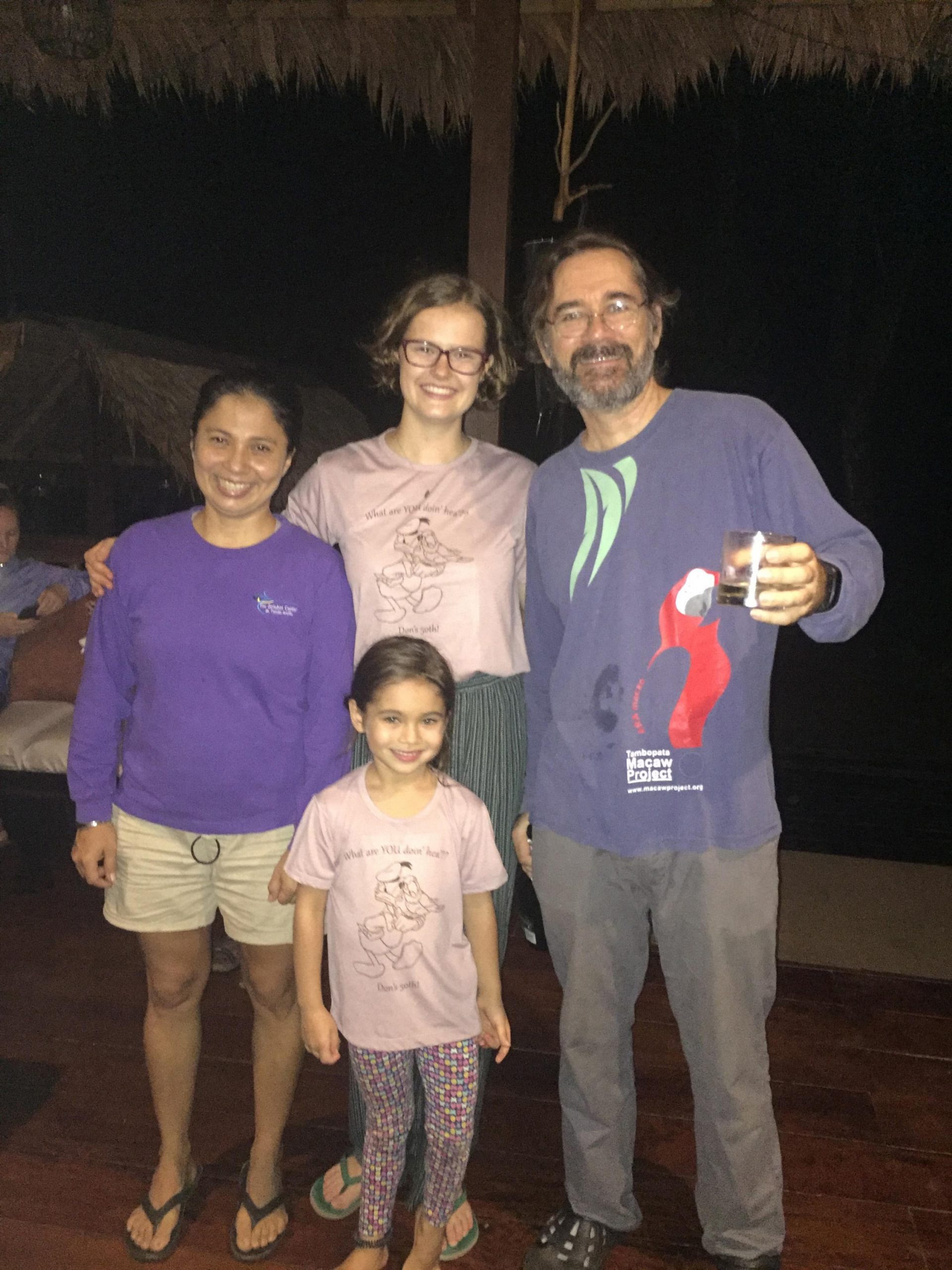

Thankfully, macaw conservation has a power couple on its side. Gabriela Vigo and her husband, Donald Brightsmith, met in 2003 at a research center in a remote pocket of the Peruvian Amazon. Now, they have a 7-year-old daughter named Mandy Lu whom they raise in the rainforest for part of each year while they co-direct the Macaw Society, formerly known as the Tambopata Macaw Project.

“In Peru, we’ve been working in a healthy parrot community to document how they function in areas that have not been impacted by humans,” Brightsmith said. “It provides a sort of baseline to which we can compare other more impacted areas.” A professor in the Schubot Exotic Bird Health Center at Texas A&M University, Brightsmith has risen to the top of his field by publishing papers about macaw clay licks, breeding, foraging, chick development, ecotourism’s role in conservation, and more.

But he will readily admit that recently, his wife has done most of the field work. In the past few years, Vigo went on jungle walks with Mandy Lu while also taking on a whole new flock of kids: tiny, bald, squawking little things that Vigo loved as if they were her own—macaw chicks.

Scarlet macaw parents lay between two and four eggs each year, but even if four chicks make it out of the egg, only one or two ever survive naturally to fledging. Years of monitoring the Macaw Society’s nest boxes revealed that breeding pairs focus their efforts on one or two of their oldest and healthiest chicks. Unless something goes wrong with the first- and second-born siblings, numbers three and four will be practically ignored from day one.

Not so with Vigo on the scene. During macaw breeding seasons from 2017 to 2019, she conducted research for her Ph.D. at Texas A&M: a study called chick relocation, or, on the board in the Macaw Society’s chick nursery, “The Hunger Games.” Unlike in the books, however, all the players survived till the end.

During the breeding seasons, volunteer tree climbers checked on scarlet macaw nests daily. When they found chicks with too many older siblings, they brought them back to the nursery, where a team of veterinarians cared for them until their opened, after about three weeks. Then it was time to find foster nests. The base criteria were similar to those which make for a good human foster home: a comfortable nest with responsible and experienced parents. The complicated part? Nests could only have one chick already in it, so that the parents would have enough food for both chicks, and new siblings had to be at the same developmental stage, so that there wasn’t any preferential treatment. It made for a difficult match-making game, but Vigo ensured that each chick ended up with a home.

Vigo fine-tuned her experiment with great success: aside from a couple of freak lightning strikes (literally), every foster chick fledged. In her words, “it showed that macaw chicks that were naturally doomed to die could be raised by foster parents and help raise population numbers.” This is great news, and not just for her Ph.D.

***

When not volunteering with the Macaw Society, Rodrigo León runs his own macaw research in Mexico’s Lacandon rainforest with Natura Mexicana. His constant bubbly energy and charming smile hide his strenuous job description: tracking the scarlet macaw nests likely to be poached, removing the chicks before anyone else can get to them, then raising them until fledging and releasing them into safer parts of the jungle.

Thanks to Vigo, it won’t always be this difficult to protect parrots. Now that her experiment has proven successful in Peru, where the macaw population is large and stable, the chick relocation method can be replicated by Natura Mexicana or any other project which seeks to conserve and grow small populations of parrots. Instead of raising the rescued chicks by hand, scientists like León can feed them for a couple of weeks, then move them into nests out of poaching range—a true win-win. Not only does it give macaw researchers more time to focus on other aspects of conservation; with adult birds teaching the chicks how to find food, fly, and live in the wild, it gives the species a greater chance of survival, one chick at a time.

Meanwhile, the Macaw Society is entering their next phase of work. Said Brightsmith: “We plan to continue our scientific research and expand our direct conservation actions in areas where macaws and parrots are in trouble,” including Mexico, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Belize, Argentina, and the USA, while maintaining a home base in southeastern Peru. Better yet, Vigo is confident that she and Brightsmith won’t be working alone. “We’ve used our research as a training platform,” she said, “to teach a new generation of naturalists and conservationists in Peru and worldwide.” Perhaps one of these young scientists will start the next society for the birds.

—

Greta Hardy-Mittell is an avid writer and conservationist from Vermont, USA. She volunteered for the Macaw Society from November 2018-January 2019, and credits the experience with changing her life.