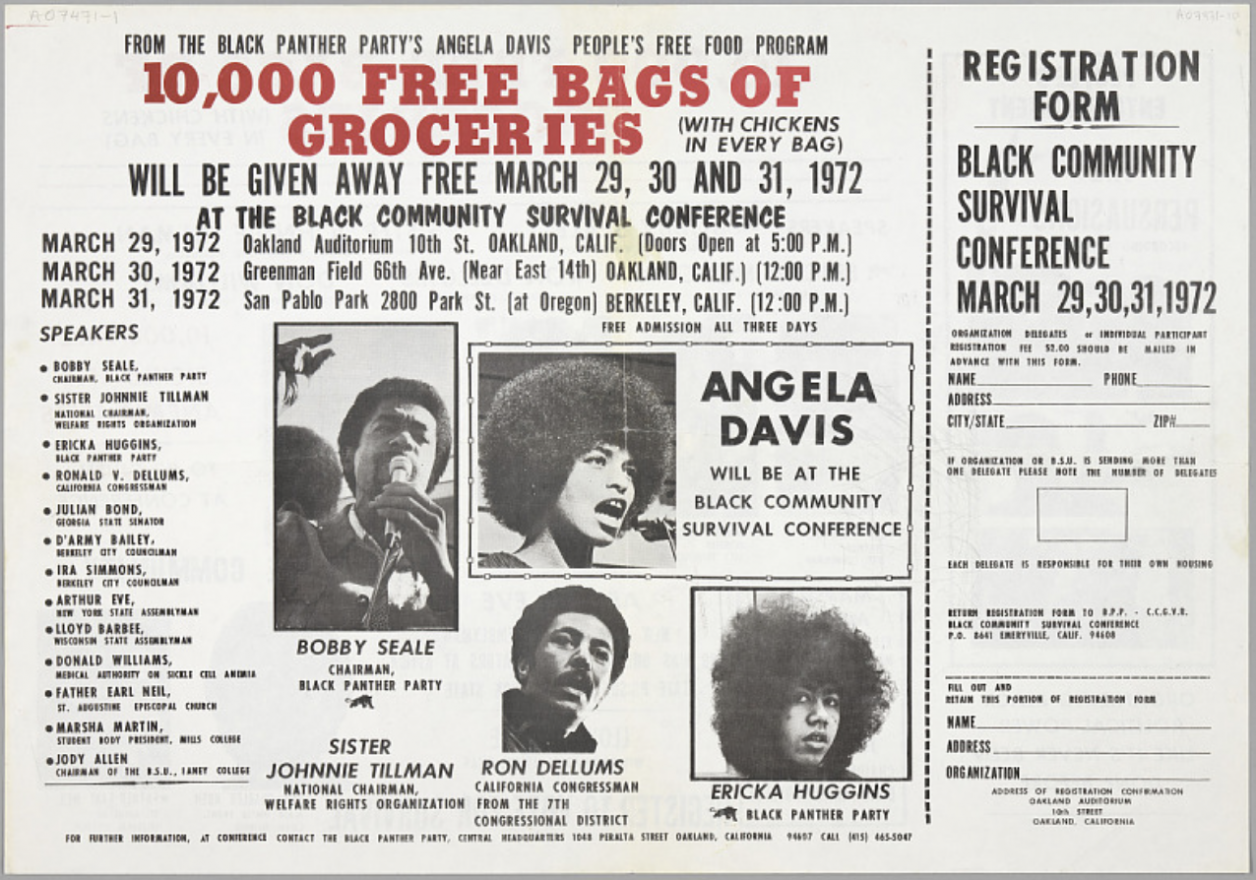

Poster advertising the 1972 Black Community Survival Conference, with a promotion by the Free Food Program. (Photo: Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 1972)

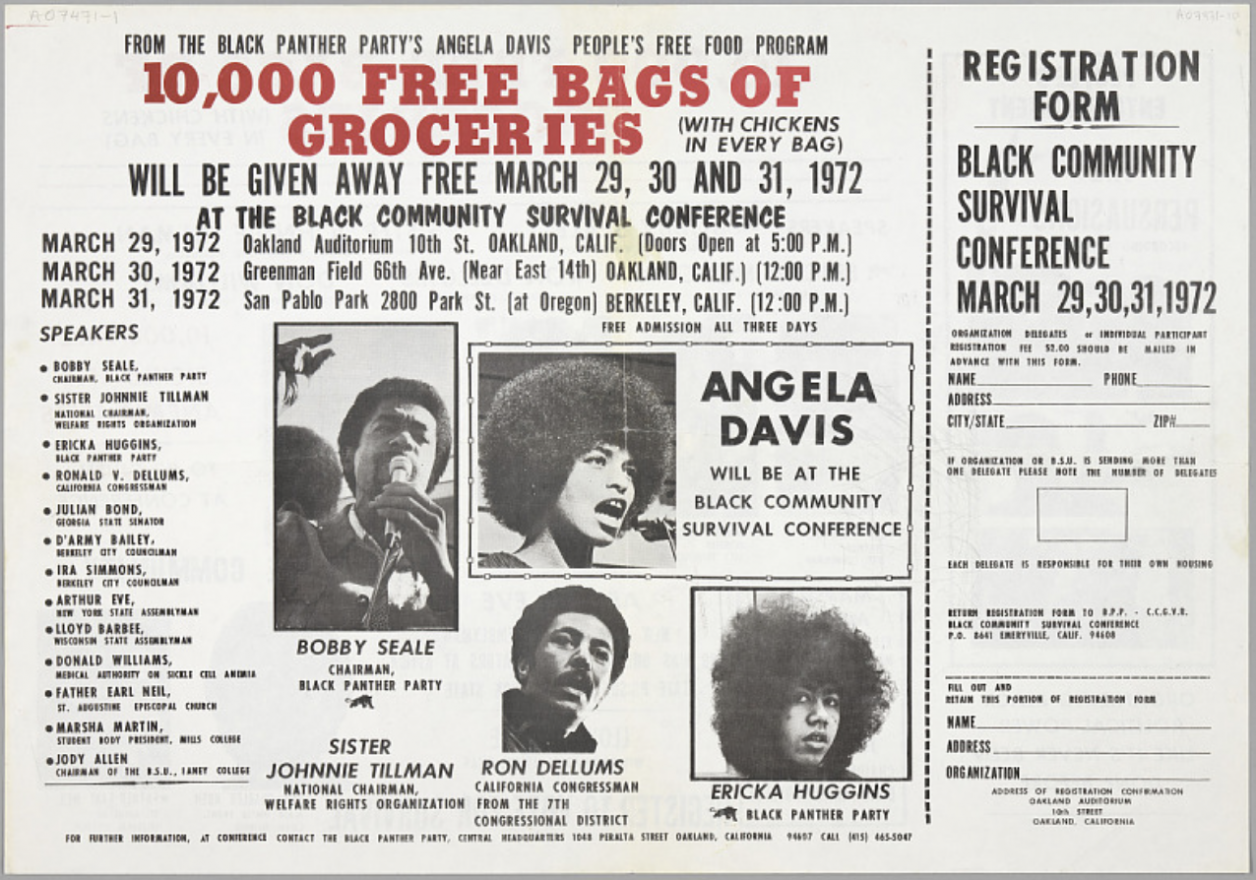

Poster advertising the 1972 Black Community Survival Conference, with a promotion by the Free Food Program. (Photo: Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 1972)

In the minds of white America, the Black Panthers are often remembered as an organization characterized by a violent militancy. Images recall the Panthers at the California Statehouse in 1967, of black berets, of guns. But this perception is narrow and misses much of the community support work the Panthers actually did. One small subsection of this work — but one with a lasting impact — was to ensure food security for the communities in which they lived and worked.

The Black Panther Party was founded in Oakland, Calif., in 1966. They preached a message of radical Black power throughout disinvested in, low-income urban areas until the early 1980s. Part of their message was policing the police — often remembered as violence — but their commitment to community safety went further.

The Panthers’ goal was to address and mitigate the injustices caused by national, endemically racist policies and programs that have systemically undermined Black communities since their inception. Policies such as the requirement for Public Housing to be segregated, often segregating previously desegregated neighborhoods when initially built, and processes like Redlining.

While The Black Panther Party’s overall goal was to bring about systemic change for Black communities, with an end to police brutality and economic subjugation, they provided important resources as a stopgap measure to sustain urban communities until radical change or revolution came. The Panthers’ “Ten Point Program,” detailed their mission — both what they wanted, and what they believed. It makes explicit calls for institutional change, and reaffirms the rights of all people to the basic necessities to live a healthy life.

10. We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice, and peace.”

— The Black Panthers Ten Point Program

The Panthers designed a series of survival programs, which targeted a wide range of needs, including food, clothing, jobs, education, health, and more — items highlighted in their mission. Four are particularly relevant to the ways we conceptualize food movements today.

The first two, Free Breakfast for School Children and the Free Food programs most explicitly provided communities with food security.

The Free Breakfast for School Children program provided hot, nutritious food, free of charge, to any child who attended the program. By the Panthers’ own admission, the purpose of the program was threefold — to feed children, to bring attention to the pervasive issue of childhood hunger, and to provide a positive introduction to the Panthers and their message for children, their parents, and the broader public. It is sometimes credited with inspiring the expansion of federally sponsored free breakfast programs, the government’s response to its wild popularity and the way it palatably introduced the Panthers’ beliefs and message.

The Free Food program addressed hunger beyond just the school day. The Panthers accomplished this through ongoing food deliveries to program participants, and periodic widespread food distribution to a wider swath of the community. A third program, the Seniors Against a Fearful Environment (SAFE) program, aimed to meet the variety of needs of elders in the communities, and included food distributions to seniors.

The exploited and oppressed people’s needs are land, bread, housing, education, freedom, clothing, justice, and peace, and the Black Panther Party shall not for a day alienate ourselves from the masses and forget their needs for survival. … When people call in to say they need food we do not spout a lot of superficial rhetoric, but see that they are fed.”

— A BPP Member named Marsha in an April 1969 Issue of The Black Panther

All of these programs relied heavily on community assistance to run. Donations of food, funds, space, and time were necessary. While many of these donations were made by community members on their own volition, the Panthers also took a more active role in securing donations. This included calling grocery stores to ask for food donations, requesting that program participants occasionally volunteer, or asking churches and community centers to lend them space for organizing and distribution. This was often an effective strategy for the Panthers, but if an entity refused to provide the requested assistance, a more aggressive tone was often adopted, including boycotts or protests of offending businesses, according to the book “Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party,” by Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin.

These three survival programs are clearly understood within the framework of food security movements, ensuring that all in the community had access to affordable, healthy food. But when coupled with the Panther’s demands for just and equal living conditions, it elevated the food movements the Panthers were a part of to a class of food justice activism.

There is another survival program of the Panthers — and the fourth on our list — that is worth mentioning in its relation to food movements. Although it was never realized due to a lack of funds, the Panthers designed a Land Banking program, which would have given the community the power to make land use determinations. These decisions could have created a space for a food sovereignty movement to flourish, as community members would have been able to create jobs and access to healthy, affordable produce growth within their community. The Panthers imagined a system that would see the “merger of land conservation and ‘human conservation’ — the interconnection between the preservation of our natural and human resources, recognizing that each have little without the other,” according to the book “The Black Panther Party: Service to the People Programs” by The Dr. Huey P. Newton Foundation and edited by David Hilliard. This could have been used for urban farms and gardens, where the means of production would have been put back into the hands of the community, but without the means of purchasing land, the Land Banking program was unfortunately never actualized.

The Panthers imagined a radical equality, never before seen in America, and were willing to take active measures to secure this reality. At the same time, they realized the immediate needs of their communities.

The creation of the survival programs was a hallmark of their approach, integrating the practical needs of the community with broader radical ideological struggle. The survival programs ingrained mutual aid and community care and were creative in adopting strategies from other movements to best fit their needs.

Racial and environmental injustice has many effects, and the survival programs were designed to address them all. Food was just one facet of their programming to right injustices. Part of the Panthers’ downfall lay in the ways managing this multitude of programs strained resources. Predicated on substantial systematic change, the programs were never designed to provide for communities indefinitely.

Across the country, urban farming organizations continue to provide mutual aid, access to healthy and affordable food, and educational opportunities to advance food security in the same spirit as the Panthers.

In Oakland, the Black Panther Party’s birthplace, organizations like Spiral Gardens, City Slicker Farms, and Phat Beets Produce, all work with the local community to provide fresh produce for free or at affordable rates, or supplies for community members to grow their own.

Similar organizations exist in major cities across the country, such as the Urban Growers Collective in Chicago, and Revision Urban Farm in Boston. They also exist in smaller cities, suburban, and rural areas, like Soul Fire Farm in Petersburg, New York; the Natwani Coalition in Northern Arizona; and Liberation Farms in Androscoggin County in Maine.

In today’s movements, taking a narrow focus has led to longer-term success for organizations. This is unlike the Panthers multifaceted approach, which when combined with pressure, white supremacist systems, and the forces that uphold them caused strain on their resources. With this narrower approach, in order to effectively challenge the systems that produce and maintain inequality, an intersectional, multi movement coalition will be necessary. To do this, many food sovereignty and justice groups partner with groups addressing other symptoms of oppression to challenge the larger system.

In this struggle, by remembering the Panthers’ approach — by utilizing mutual aid networks and uplifting urban communities from within — organizations can address the current realities or low-income communities while striving as a collective for systemic change.