Michael Kappel/CC BY-NC 2.0

Michael Kappel/CC BY-NC 2.0

By Jack Austin

Chicago is one of the cleanest electricity cities on earth, powered largely by a nuclear fleet most residents don’t even know they rely on. The city’s relationship with atomic energy runs deep: The first controlled nuclear chain reaction happened under the stands of Stagg Field at the University of Chicago in 1942, and scientists at the Argonne National Laboratory went on to design reactors that shaped the nation’s nuclear era. Decades later, that legacy is still embedded in the region’s infrastructure, quietly delivering some of the lowest-carbon electricity in any major world city.

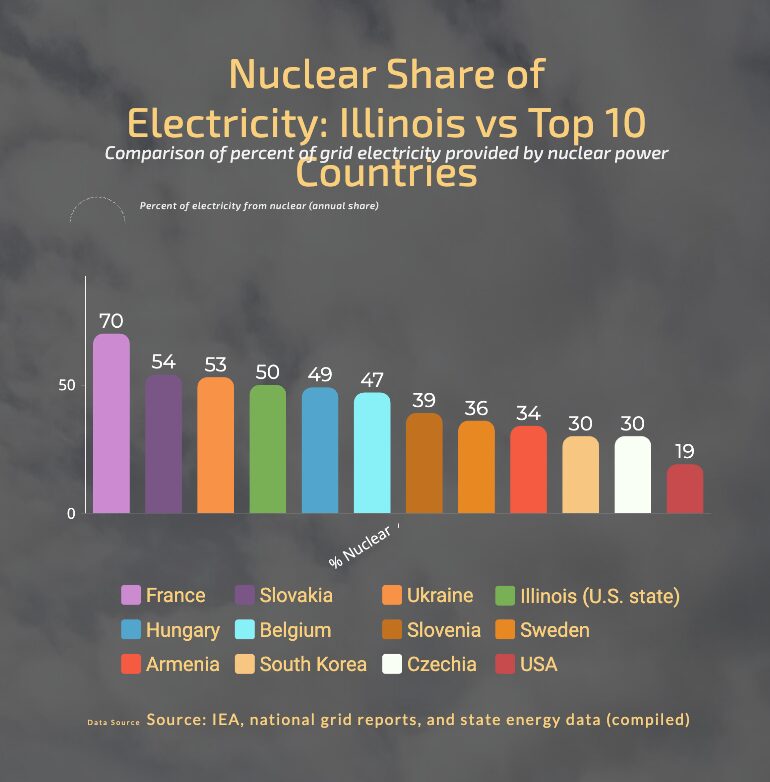

Among the world’s large population centers, Chicago’s grid ranks among the cleanest in North America and, on a megacity scale, is second only to Paris, dominated by low-carbon nuclear generation. Some smaller cities worldwide achieve low carbon intensity grids with large hydro resources.

“If you just look at the data, it’s pretty obvious that we have one of the cleanest grids in America,” nuclear advocate Michael McLean said. “The amount of electricity we consume in the city is almost 100% like the same amount that’s produced by the nuclear plants on the grid.”

Chicago’s carbon performance is unusual in a world where most megacities depend heavily on fossil fuels. Tokyo and New York City, for instance, rely substantially on natural gas. Seoul and Shanghai remain coal-heavy. Even places known for climate ambition, such as London or Berlin cannot match Chicago’s emissions profile. The region landed in this position not because of a recent burst of clean-energy investment, but because of decisions made decades ago, when Illinois built a fleet of large, reliable reactors inspired by Argonne’s experimental work.

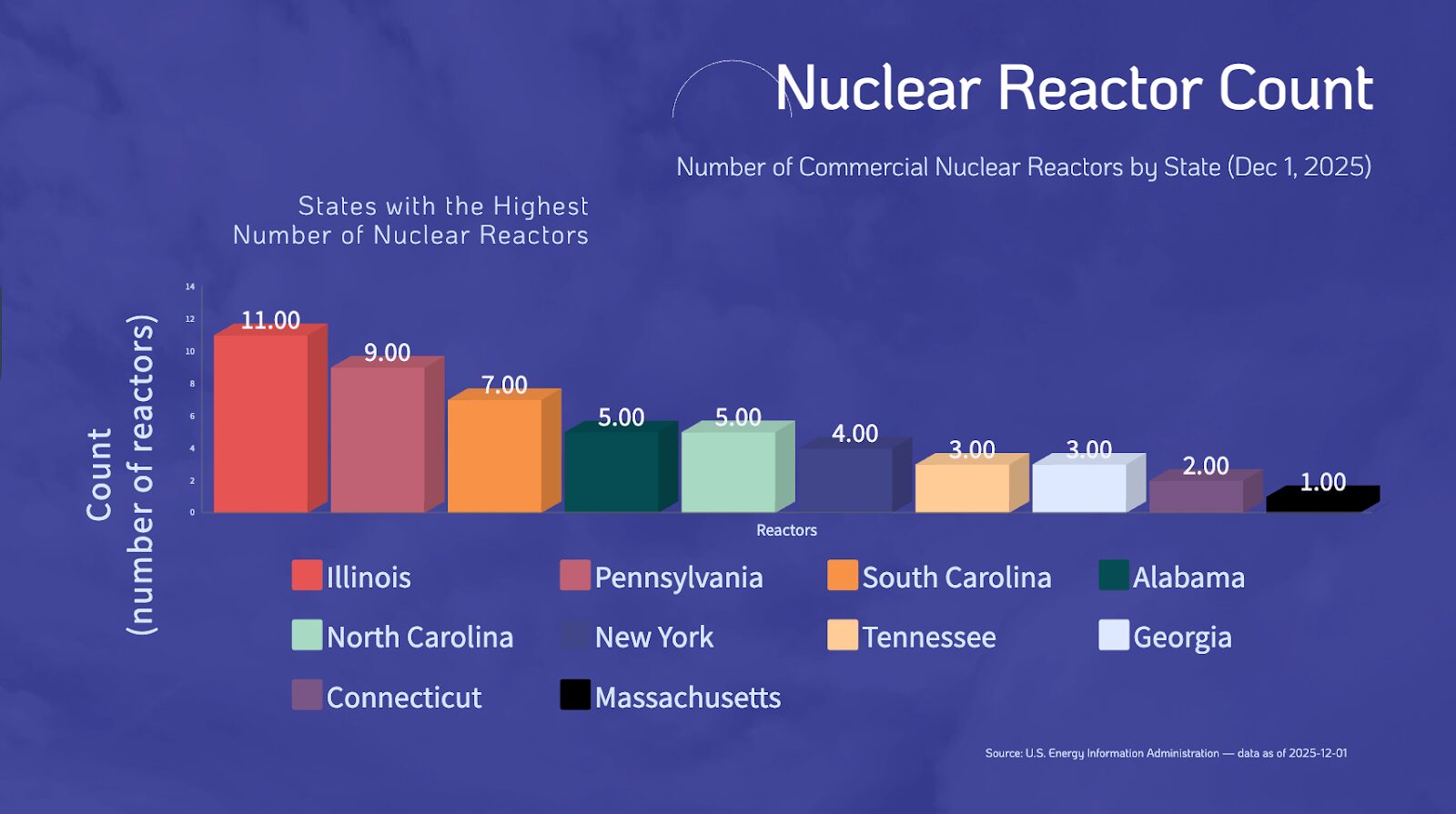

Illinois’ clean-energy foundation emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, with large reactors built on Argonne’s earlier experimental designs. Nuclear now produces more than half of Illinois’ electricity. Retired Argonne engineer Roger Blomquist said the lab’s early research into boiling water reactors helped propel the state into a position of national leadership. Argonne designed and operated Dresden, the nation’s first full-scale, privately financed commercial nuclear plant, which opened in 1960.

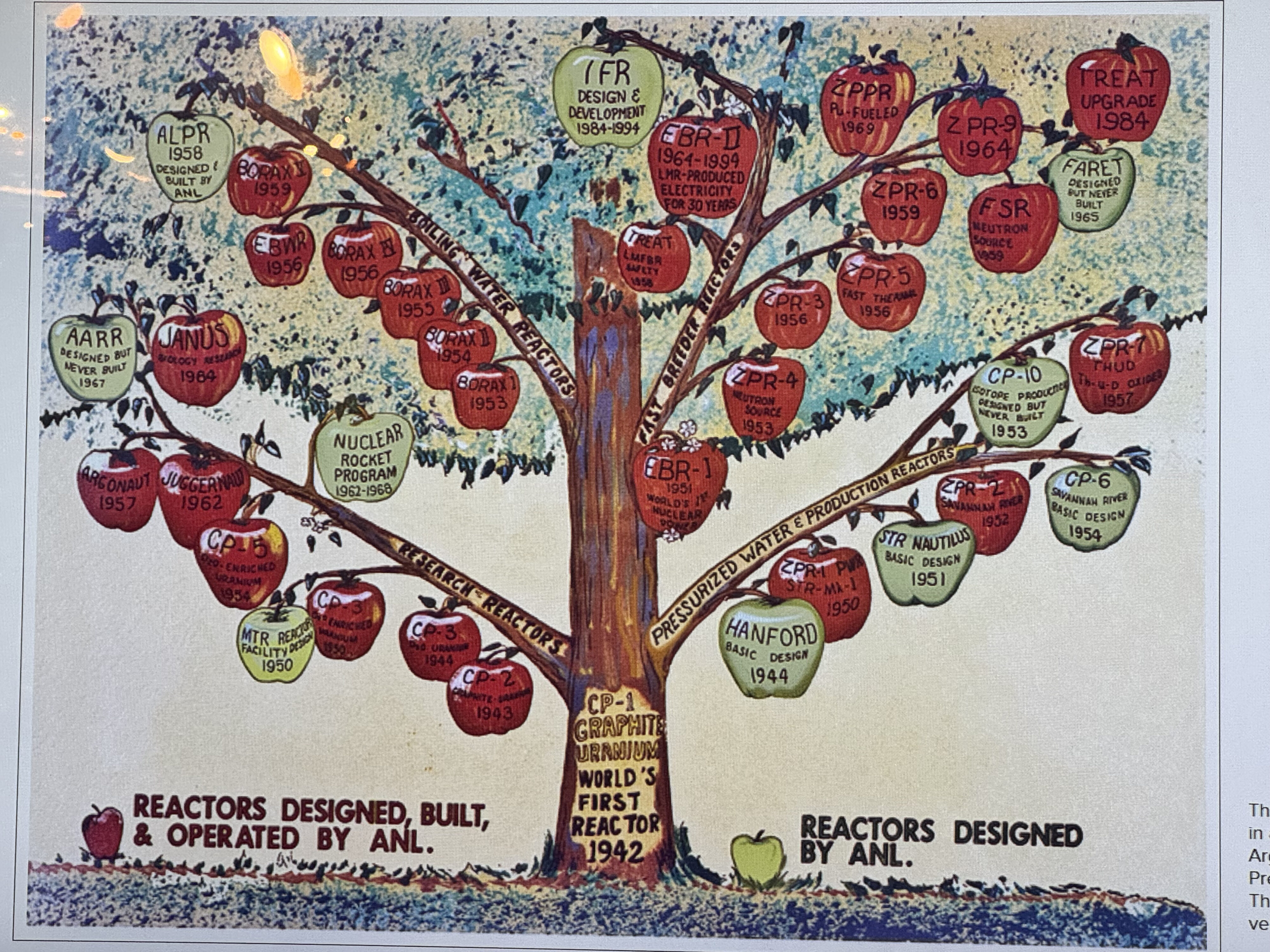

“Argonne was told to explore peaceful applications of nuclear power,” Blomquist said. “Over the decades, Argonne built about 30 reactors of various power levels. They were just physics experiments, but still critical — they still had neutron chain reactions.”

From those experiments emerged the reactors that anchor Illinois’ grid today. Dresden Units 2 and 3, LaSalle, Byron, and Braidwood came online between 1971 and 1988, together offering 8.6 gigawatts of capacity — enough to power roughly 6.4 million homes. Their construction coincided with a broader nationwide surge in nuclear development, before a series of economic and political factors slowed expansion across the country.

Several factors in the 1970s and 1980s slowed nuclear expansion. Early plants operated at around 60% capacity, and regulators required retrofits and additional safety systems at newly licensed plants, changes that increased costs and created uncertainty. Nationally, about 100 planned plants were canceled, many already partially constructed.

Then came the 1979 Three Mile Island accident, which, despite causing no injuries or environmental contamination, sent shockwaves through the public. The idea of nuclear catastrophe took hold quickly, especially as the fictional accident in the film The China Syndrome premiered just 12 days earlier.

In the accident’s wake, Chicagoan David Kraft founded the Nuclear Energy Information Service (NEIS), a non-profit that has opposed nuclear power since 1981. Kraft said he initially supported nuclear energy, but incidents combined with deepening public fears led him to question its economics and safety. NEIS frames its opposition around cost overruns, accident risk, and radioactive waste, envisioning a future grid built primarily on rooftop and farm-scale solar, paired with large energy storage systems.

Energy historian Emmet Penney criticized that vision as unrealistic at the scale required for megacities. “California has spent $15 billion on battery storage in the last decade,” he said. “Total in-state battery storage capacity is less than the Everett LNG terminal in Massachusetts. Illinois’ weather is less conducive for solar than California. Those facts almost speak for themselves.”

NEIS became politically influential in Illinois. The group played a key role in lobbying for the 1987 Illinois nuclear construction moratorium, which prohibited new reactor approvals until a federal waste solution existed. Kraft said NEIS fought to defend the moratorium through the 1990s and 2000s against multiple attempts at repeal.

Public and political attitudes began to shift by the mid-2010s. In 2016, prominent pro-nuclear advocates — including Alan Medsker, Michael Shellenberger, and climate scientist James Hansen, Ph.D. — held high-profile events in Illinois promoting nuclear as a critical climate solution. Hansen, Shellenberger, and philanthropist Rachel Pritzker appeared together on a panel emphasizing both the environmental necessity and moral responsibility of preserving nuclear capacity.

Medsker began building relationships with lawmakers, including State Senator Mark Walker, who shifted from neutral to strongly supportive of nuclear energy. Walker introduced House Bill 1079 in 2023, which removed the portion of the Public Utilities Act that blocked new nuclear construction until a high-level waste solution was approved. The House Public Utilities Committee passed the bill 18–3, and Senator Sue Rezin introduced a companion measure in the Senate.

But Governor J.B. Pritzker vetoed the bill over regulatory concerns. A compromise — House Bill 2473 — passed later, lifting the moratorium only for small modular reactors (SMRs) of 300 MW or less.

This partial repeal left many legislators unsatisfied. State Rep. Dave Vella authored Senate Bill 25, the Clean and Reliable Grid Affordability Act, which fully lifted the ban for all reactor types. The legislature passed the bill in October.

Vella said generational attitudes played a major role. “Older environmentalists saw nuclear as worse than coal. But younger people see climate change as the threat. The only way to replace coal is with nuclear — there’s not enough solar panels and wind to do that.”

Blomquist, McLean, and Vella all emphasized nuclear’s value not only for decarbonization but also for reliability and energy security. As data centers, manufacturing, and electrified heating demand grow, the state will need more firm, clean power — something nuclear provides with unmatched consistency, according to McLean.

Medsker noted that Illinois’ reactors have become some of the most reliable in the world, with operators now extending plant lifetimes toward 80 years. That longevity, he argued, makes nuclear plants among the most durable infrastructure investments available.

The repeal of the moratorium opens the door to an array of advanced nuclear technologies. While the initial legislation emphasizes SMRs, smaller reactors that can be built modularly in factories, Illinois may eventually pursue larger light-water reactors similar to the successful fleet it already operates. Either path could help decarbonize the remaining 30% of the Illinois grid, which still relies on fossil fuels.

McLean stressed that electrifying transportation and heating will require massive amounts of additional clean power. Without new firm generation, Illinois could face reliability challenges. “We need clean energy to support everything from EV charging to industry,” he said.

Engineer Tim Smyth compared Illinois to Ontario, Canada, which has one of the cleanest grids in the Western Hemisphere. While Ontario uses both hydro and nuclear — reducing its carbon intensity to about 35 grams CO₂/kWh — Illinois achieves roughly similar performance with far less hydro. Still, Smyth noted, Illinois trails France, where 75% nuclear generation allows the country to export electricity across Europe.

For Medsker, the stakes go beyond emissions. Nuclear energy expands access to affordable electricity while avoiding the air-pollution impacts of coal and gas. McLean said many Illinoisans simply don’t realize how clean their electricity already is — or that nuclear power is the reason. “Public perception has been shaped by decades of rate hikes and bailout narratives,” he said. “People don’t see that our grid is already one of the lowest-carbon in the world.”

Illinois’ geography strengthens nuclear’s case. With long, cold winters and limited winter sunlight, the state cannot lean heavily on solar. Wind helps, but it is variable. Nuclear fills the gap: steady, high-capacity, independent of weather.

Vella sees SMRs in particular as transforming the state’s energy landscape. “A small reactor could power a city like Rockford entirely on its own grid,” he said. He imagines distributed reactors sited across Chicago’s neighborhoods, providing resilience alongside environmental and economic benefits. “As people realize nuclear power is safe and good, third- and fourth-generation plants are going to be coming online. The technology is not quite there yet, but it’s getting close.”

Chicago doesn’t market itself as a nuclear city. There are no tourism campaigns built around its unique energy profile, no public monuments to the reactors that power it. But by the numbers, Chicago is a global outlier — a megacity burning almost no fossil fuels to keep the lights on.

In an era of growing electrification, new industrial demand, and rising concerns about carbon pollution, Chicago’s nuclear backbone offers a model for what a clean, reliable grid can look like. Whether Illinois chooses advanced reactors, SMRs, or more large-scale plants, its nuclear foundation remains the central reason the city is already one of the cleanest megacities in the world — and why it may be among the best prepared for the energy challenges ahead.

Investors are increasingly stepping up to support nuclear energy, according to Madi Hilly, a partner at the energy consulting firm Radiant Energy Group. One example is Meta’s power purchase agreement (PPA) with Constellation, an American energy company and nuclear power plant operator, which supports the relicensing, continued operation, and expansion of the Clinton nuclear plant in Illinois.

Hilly said that nationwide, companies are signing PPAs with existing nuclear plants to secure reliable power, in some cases helping bring reactors back into operation. While these agreements are not directly resulting in new next-generation nuclear plants, they are expanding overall capacity, Hilly said.

On the financing side, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office can cover up to 80 percent of the cost of new nuclear projects, which often run into the billions of dollars, and projects may also qualify for a 30–50 percent investment tax credit once reactors enter service. Despite strong federal support, Hilly does not view Illinois as a frontrunner for new nuclear construction, citing anti-nuclear policy, rhetoric, and the state’s continued moratorium on new reactors.

“I think Illinois will have to do more to make it clear that we want large nuclear plants, that we’re willing to play ball, and that we’d like help from the federal government to get that done,” Hilly said.

Looking ahead to the next major nuclear build in the U.S., Hilly said she expects expansion to occur first in more openly pro-nuclear states, such as New York. She said Constellation is bullish on expanding its capacity and is actively working with New York officials to develop new reactors upstate. Still, Hilly said she could envision a new reactor being built in Illinois within the next decade.